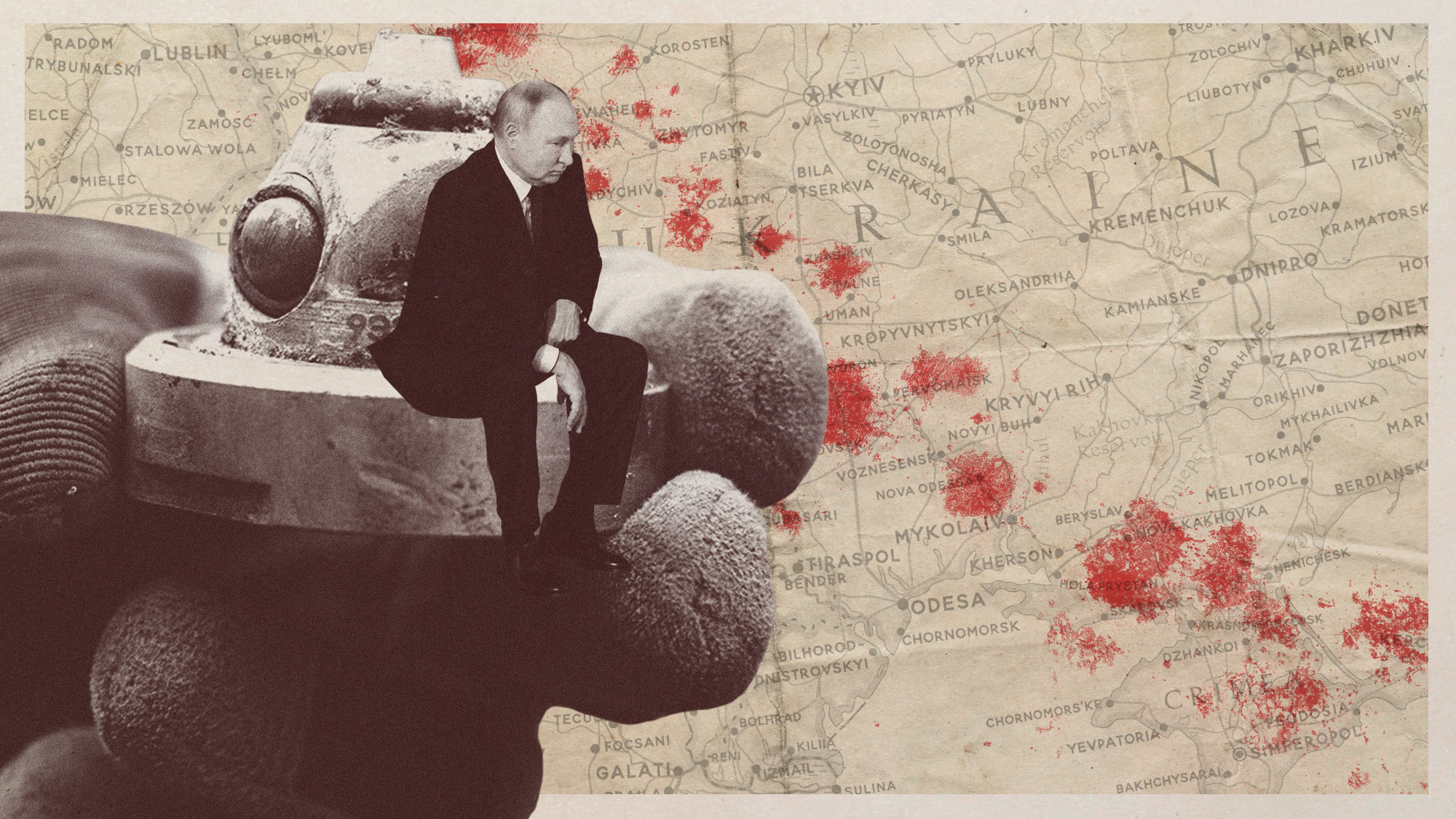

Ottawa Treaty: why are Russia's neighbours leaving anti-landmine agreement?

Ukraine to follow Poland, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia as Nato looks to build a new ‘Iron Curtain' of millions of landmines

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"The war ends. The landmine goes on killing," said Jody Williams, who led the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, in her 1997 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech.

The Ottawa Treaty signed that year banned the use of anti-personnel landmines as well as the ability to "develop, produce, otherwise acquire, stockpile, retain or transfer to anyone, directly or indirectly, anti-personnel mines". It has since been ratified by 160 countries, but not by the US, China or, crucially, Russia.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has announced his intention to withdraw from the convention, following similar decisions by Poland, Finland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the commentators say?

It is no coincidence that these countries together guard 2,150 miles of Nato's frontier with Russia and its client state of Belarus.

In the three years since the invasion of Ukraine, they have all made "significant investments to better secure these borders, for example with fences and surveillance systems", said DW. "Now, a new plan is in the works: landmines."

The Telegraph's chief foreign affairs commentator David Blair has reported plans to build a "new 'Iron Curtain' – with millions of landmines".

"Banning them might have been a luxury cause for a dominant West in the years of safety after the Cold War, yet no longer." Now, "as Europe re-arms to deter Putin, what was once unconscionable has become unavoidable".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

For Zelenskyy, whose country is already at war and now the "most mined" in the world, according to Euronews, withdrawing from the convention will help level the situation on the battlefield. The Kremlin has by far the world's largest stockpile of anti-personnel mines, with an estimated 26 million, and has used them with "utmost cynicism in Ukrainian territory, he said. The problem, said Zelenskyy, is that anti-personnel mines are "often the instrument for which nothing can be substituted for defence purposes".

Small explosive devices designed to detonate under a person's weight, "they are attractive to militaries because they can block an enemy advance, channel forces into kill zones and protect defensive positions," said The Times. They are also a "serious threat to civilians, often remaining lethal for decades after a conflict has ended".

What next?

The timing of the departures is "related to threat assessments shared by Nato countries", said Al Jazeera.

"Liberal-democratic" states across northern Europe "are in agreement", defence expert Francis Tusa said in The Independent: if Kyiv "loses its struggle against Russia, the latter may be emboldened to take military action against the Baltic states, Finland, or even Poland".

Many defence specialists agree the timeline for this is "within three to five years", making the need to prepare for a potential Russian invasion with all the tools available a priority for those on the frontline.

But anti-landmine campaigners "worry this is part of a larger trend, with the rules of war and international humanitarian norms being eroded more broadly", said The Irish Times.

In the context of conflict and geopolitical tension escalating around the world "it is impossible not to feel that we are going backwards, seeing threats to the international rules-based order, and most importantly to the frameworks that have long been in place to protect civilians", said Josephine Dresner, director of policy with the Mines Advisory Group.

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straits

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in the remote Danish protectorate shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

What is ‘Arctic Sentry’ and will it deter Russia and China?

What is ‘Arctic Sentry’ and will it deter Russia and China?Today’s Big Question Nato considers joint operation and intelligence sharing in Arctic region, in face of Trump’s threats to seize Greenland for ‘protection’

-

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expire

New START: the final US-Russia nuclear treaty about to expireThe Explainer The last agreement between Washington and Moscow expires within weeks

-

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?

What would a UK deployment to Ukraine look like?Today's Big Question Security agreement commits British and French forces in event of ceasefire

-

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?

Would Europe defend Greenland from US aggression?Today’s Big Question ‘Mildness’ of EU pushback against Trump provocation ‘illustrates the bind Europe finds itself in’

-

Did Trump just end the US-Europe alliance?

Did Trump just end the US-Europe alliance?Today's Big Question New US national security policy drops ‘grenade’ on Europe and should serve as ‘the mother of all wake-up calls’

-

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?

Is conscription the answer to Europe’s security woes?Today's Big Question How best to boost troop numbers to deal with Russian threat is ‘prompting fierce and soul-searching debates’

-

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?

Trump peace deal: an offer Zelenskyy can’t refuse?Today’s Big Question ‘Unpalatable’ US plan may strengthen embattled Ukrainian president at home

-

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missile

Vladimir Putin’s ‘nuclear tsunami’ missileThe Explainer Russian president has boasted that there is no way to intercept the new weapon