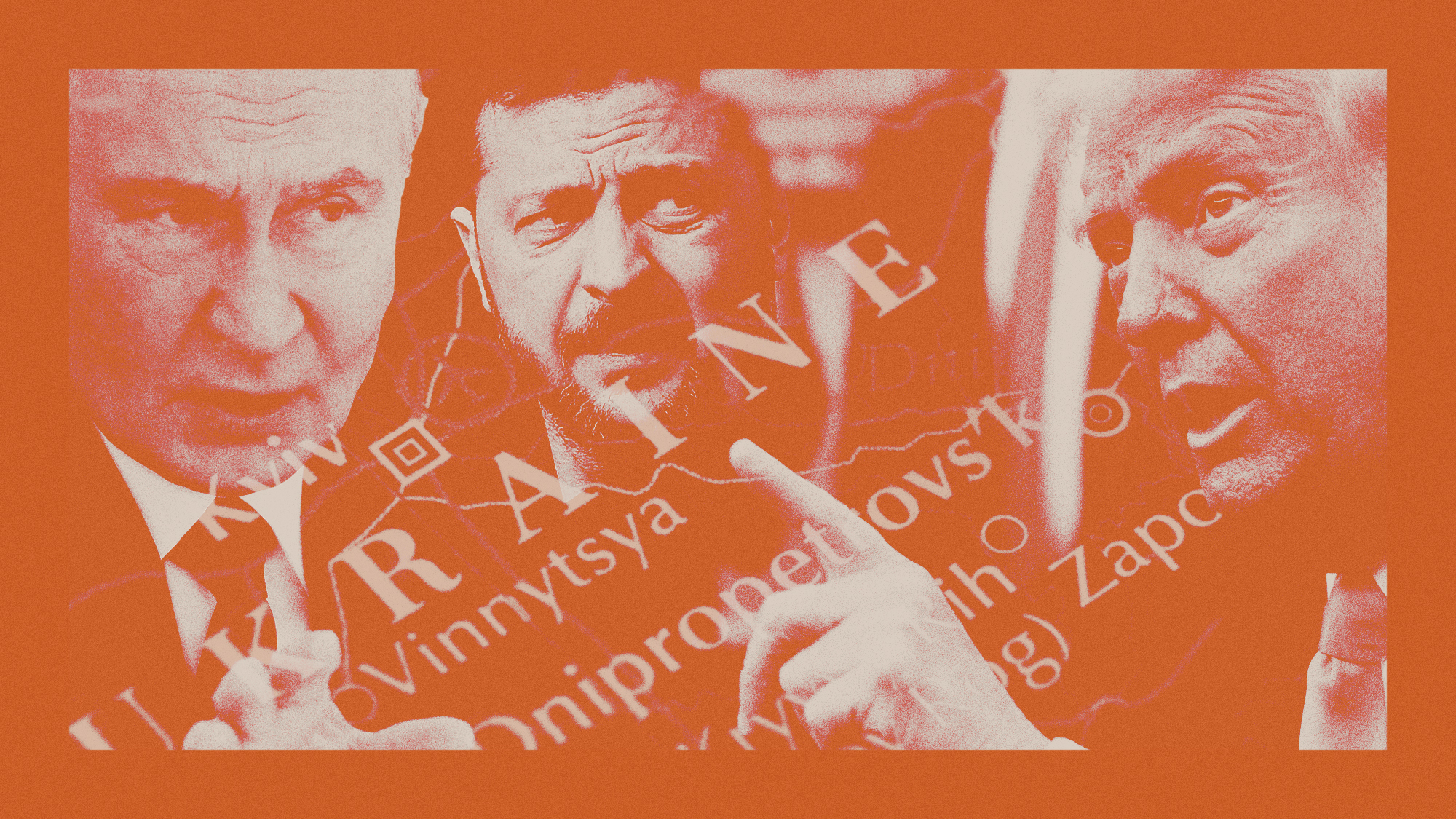

Explained: Vladimir Putin’s key justifications for Ukraine invasion

Russian president’s denial of neighbouring nation’s statehood laid ‘groundwork for war’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Vladimir Putin has been roundly condemned for attacking the notion of Ukrainian statehood in an “angry” and “dismissive” speech that put a new spin on the history of Russia’s relations with its eastern European neighbour.

In the Russian president’s “version of Ukraine’s history”, the territory now controlled by Kyiv “was always part of Russia”, said Associated Press (AP) editor-at-large John Daniszewski. But “while that serves his purpose, it is also a fiction” that denies Ukraine’s “own 1,000-year history”.

World leaders have dismissed Putin’s claims in his address to the nation on Monday, when he signed a decree recognising the independence of the separatist Ukrainian regions of Luhansk and Donetsk, collectively known as Donbas. But those claims nonetheless lay the “groundwork for war”, wrote Daniszewski.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

1. Ukraine ‘is Russia’

During his televised address, Putin “buoyed his case for codifying the cleavage of two rebel territories from Ukraine by arguing that the very idea of Ukrainian statehood was a fiction”, The New York Times (NYT) reported.

“With a conviction of an authoritarian unburdened by historical nuance”, the paper continued, the Russian leader “declared Ukraine an invention of the Bolshevik revolutionary leader, Vladimir Lenin”. According to Putin, Lenin “endowed Ukraine with a sense of statehood by allowing it autonomy within the newly created Soviet state”.

Experts do not dispute that the Bolsheviks recognised Ukraine as a separate socialist republic in 1917, following the foundation of the Soviet Union. But Ukraine can trace its history back to Kievan Rus’, a loose federation dating from the Middle Ages that is widely accepted to form the basis of the country’s national identity.

All the same, Putin’s contrary claim that “there had never been a historical Ukraine until Soviet times” is being used to justify a potential invasion of Ukraine, said AP’s Daniszewski.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And “as with all historical narratives”, he continued, “there were elements of truth in what Putin was saying”, in that “Ukrainians and Russians are related eastern Slavic peoples whose destinies have been both intertwined and separated throughout history”.

But in justifying a potential Russian occupation, Putin chose to “focus on the time of Russia’s maximum dominance over Ukraine”, overlooking “that it has been a separate state recognised by international treaties and explicitly by Russia over the last 30 years”.

2. Russian ‘genocide’

Another key element of the Kremlin’s grounds for a conflict with Ukraine is allegations from Moscow that the government in Kyiv is committing “genocide” against ethnic Russians in the two separatist-controlled regions.

The claim has been dismissed as “absurd” by the Washington-based Atlantic Council think tank, but Putin justified the deployment this week of troops to Luhansk and Donetsk by arguing that they were “peacekeepers”.

His government has repeatedly claimed that the Ukrainian military has targeted civilians with historic links to Russia during the shadow war that has been taking place in the Donbas region since 2014.

But “there have been no serious efforts to support this explosive claim”, the Atlantic Council said. Instead, the allegations “represent a grotesque distortion of reality” that seeks to “blame the victims for a war of aggression orchestrated by Moscow that has killed thousands of Ukrainians and forced millions to flee their homes”.

The Kremlin has aggressively pushed back against Western leaders who have rubbished the genocide claims. The Foreign Ministry said that such a dismissal by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz following talks with Putin last week was “unacceptable”.

But while Moscow is yet to produce evidence of a “genocide” against ethnic Russians in the Donbas, “detailed accounts of Kremlin atrocities in eastern Ukraine” do exist, the Atlantic Council reported. “They make for grim reading”, highlighting ”war crimes that have taken place amid the lawlessness of Russian-occupied eastern Ukraine”.

3. Nato expansion

Putin has long maintained that Nato has overstretched its mandate by expanding eastwards and admitting members that border Russia.

The Kremlin wants “an end to Nato expansion, a rollback of previous expansion, a removal of American nuclear weapons from Europe and a Russian sphere of influence”, wrote Seth G. Jones, director of international security at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

Putin has demanded that Nato publicly renounce a pledge that Ukraine will one day be allowed to join the alliance, arguing that “the best solution to the Ukraine crisis would be for Kyiv to independently disavow its ambitions to join Nato”, The Times said.

Despite Nato reportedly having no immediate plans to admit the eastern European country to the military alliance, Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has maintained that it is a “matter of relations between Ukraine and the alliance”.

“It certainly should not be the choice of any state in any part of the world,” he said in mid-December, following talks with Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. Aggression from Moscow “has pushed Ukraine into Nato”, Zelenskyy warned.

Ex-Labour minister George Robertson, who led Nato between 1999 and 2003, has said Putin wanted to join the alliance early in his rule. Robertson told The Guardian that the Russian leader “wanted to be part of that secure, stable prosperous West that Russia was out of at the time”.

That may explain why Putin’s latest attack on Ukrainian statehood “sounded like a fever dream”, wrote BBC diplomatic correspondent Paul Adams. “Why, he asked, did Nato make an enemy of Russia”, underlining “that the Kremlin remains deeply resentful of the way history panned out”.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisonings

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisoningsThe Explainer ‘Precise’ and ‘deniable’, the Kremlin’s use of poison to silence critics has become a ’geopolitical signature flourish’

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain