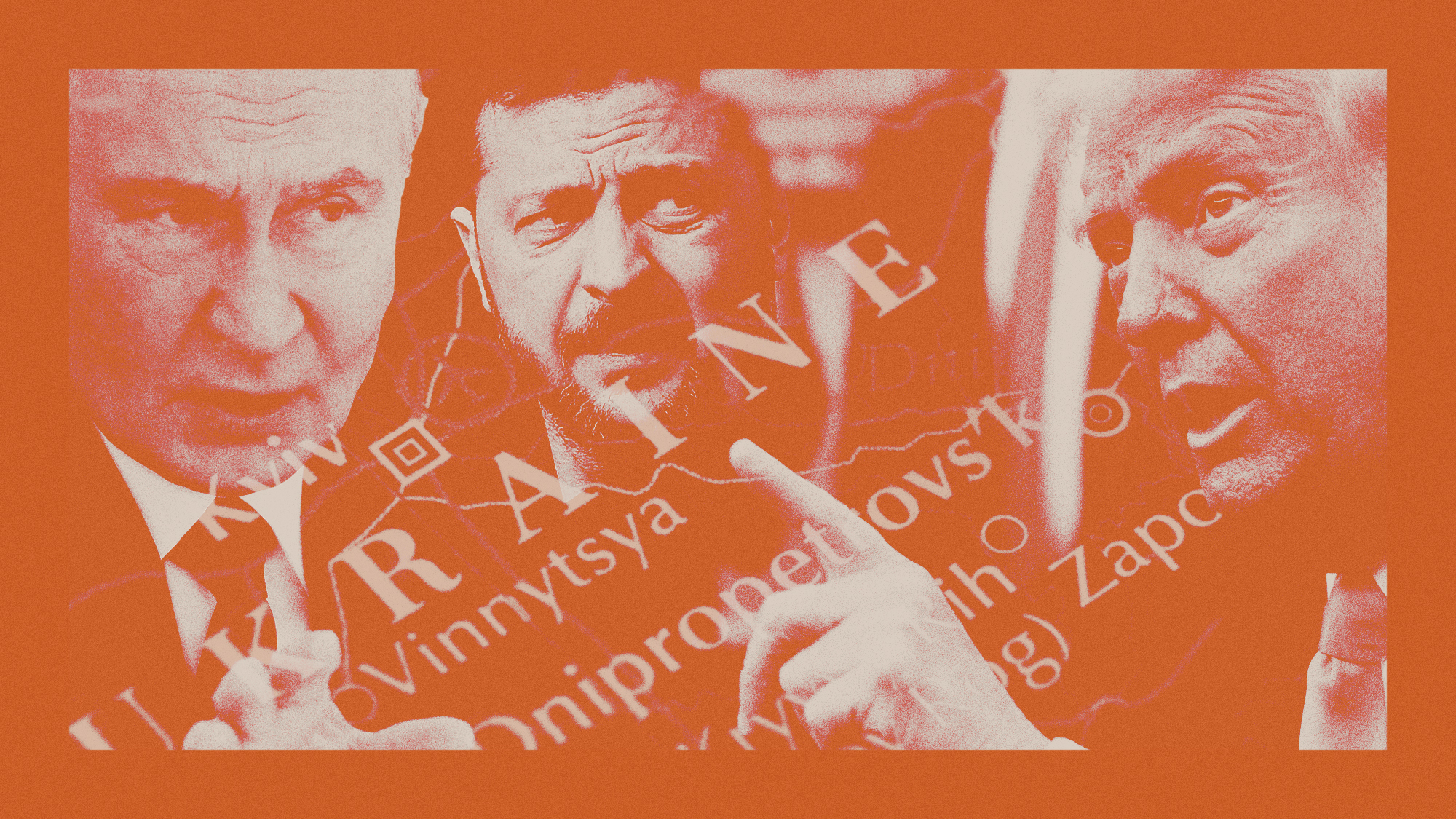

Why Vladimir Putin is so hung up about Nato

Ukraine is not joining the alliance – but the prospect has the Kremlin worried

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Weeks after Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg warned of the “real risk for a new armed conflict in Europe” following the breakdown of talks with Russia, the world remains braced for Moscow to launch an invasion of Ukraine.

Yet while US officials have cautioned that Russia could attack at a moment’s notice, analysts are puzzling over the paradox of why Vladimir Putin is risking war over something that the military alliance has no plans to do.

“Ukraine has long aspired to join Nato,” said the Associated Press (AP), “but the alliance is not about to offer an invitation, due in part to Ukraine’s official corruption, shortcomings in its defence establishment, and its lack of control over its international borders.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So what is the Russian president’s big issue with the military alliance – and is a compromise achievable?

Security guarantees

Moscow’s complaints in talks with Nato “go beyond the question of Ukraine’s association” with the Western alliance, AP reported. But “that link is central to his complaint that the West has pushed him to the limits of his patience by edging closer to Russian borders”.

Putin’s major concern is that “Nato expansion years ago has enhanced its security at the expense of Russia’s”, the news agency continued. So he wants “a legal guarantee that Ukraine be denied Nato membership, knowing that Nato as a matter of principle has never excluded potential membership for any European country – even Russia”.

Although the alliance is refusing to give such a guarantee, the absence of any plans to offer Ukraine membership either has left many experts “optimistic that the situation can resolve without what could be Europe’s first major land war in decades”, Vox reported.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Mark Galeotti, a professor of Russian security affairs at University College London, told the site that “Russians themselves have no enthusiasm for any kind of a war”. But the current dispute is “not about Russia”, he said. “It’s about Putin.”

The Russian president is “worried about the thought of Nato’s forces being based in Ukraine and often “talks about missiles near the [Ukrainian] city of Kharkiv that could hit Moscow in five minutes”, Galeotti explained.

“In reality, these are very, very implausible scenarios,” he added. But “the last thing he wants is for his legacy in the history books to be the guy who lost Ukraine, the guy who rolled over and let Nato and the West have their way”.

Putin’s fears have been exacerbated by Nato’s “existing military presence in Eastern Europe, which includes a regularly rotating series of exercises” in former Soviet states Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, AP said.

He also “opposes Nato’s missile defence presence in Romania, a former Soviet satellite state, and a similar base under development in Poland”, the agency reported, and has argued that “they could be converted to offensive weapons capable of threatening Russia”.

In other words, Putin’s issue with Nato is founded in the threat that the alliance could represent to Russia in the future.

Strategic error?

On the same day that Nato’s Stoltenberg warned of a “real risk” of war in Europe, Russia’s Deputy Defence Minister Alexander Fomin was quoted in Russian state-owned media as saying that relations with Nato were at a “critically low level”.

All the same, leaders of Nato member states, including French President Emmanuel Macron, have maintained an open line with the Kremlin. And Moscow has lent heavily on Germany, a country seen by many as “Nato’s weakest link”, according to Peter Rough, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Hudson Institute.

“Not only do the majority of Germans view military power as antiquated, but they draw a red line around actions that could lead to Russian deaths,” Rough wrote in an article for The Wall Street Journal. “Any war with Russia, German historical memory teaches, will lead to ruin.”

For Putin, “separating the most important country in Europe from America is never far from his mind”, he warned. And through his escalations over Ukraine, the president has “has driven a wedge” between Berlin and other Nato nations.

In 2008, Nato decided against giving countries such as Ukraine and Georgia, both of which have voiced an interest in joining the alliance, “a Membership Action Plan” that would have provided “a pathway to eventual membership”, AP reported.

Germany and France “strongly opposed moving Ukraine toward membership”, the news agency continued, and the “broader view within Nato was that Ukraine would have to complete far-reaching government reforms before becoming a candidate for membership”.

Some analysts argue that Putin’s aggression has strengthened the alliance’s resolve. Ian Bremmer, founder of the Eurasia Group political risk research firm, tweeted that Russia’s president has helped “to create a strong, more aligned” Nato.

“Russia’s military build-up has also revived talk in Finland and Sweden of joining Nato,” Voice of America reported. Finnish President Sauli Niinisto has stressed his country’s “room to manoeuver and freedom of choice” when it comes to joining the alliance.

Given this result, aggression over Ukrainian membership could prove to have been a strategic misstep by the infamously difficult to read Russian leader.

After all, said AP, “while Nato’s door is open” to new members, the reality is that “Ukraine won’t fit through anytime soon”.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisonings

Alexei Navalny and Russia’s history of poisoningsThe Explainer ‘Precise’ and ‘deniable’, the Kremlin’s use of poison to silence critics has become a ’geopolitical signature flourish’

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain