Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear Armageddon

After the US and Soviet Union became capable of Mutually Assured Destruction, safeguards were put in place to prevent World War Three

Tim Williamson

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article originally appeared in History of War magazine issue 138.

From the earliest days of the Cold War, both the US and the USSR had nuclear weapons, but only one means of delivering a strike – long-range, strategic bombers. As the conflict wore on, technological advances changed that, and soon the two sides were capable of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD).

"The phrase was first coined by the US Secretary of State Robert McNamara in the early 1960s," historian and author Roger Hermiston told History of War. "In 1953 the respective nuclear weapon stockpiles of the three countries were USA: 1,169; Soviet Union: 120; and the United Kingdom: one."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Throughout the 1950s, both superpowers began developing intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) armed with nuclear warheads which they stored underground in protective silos. In some cases, these missiles had several warheads and were known as Multiple Independent Re-Entrant Vehicles (MIRVs).

President John F. Kennedy observes the launch of a Polaris missile during tests, 1963

In addition, both sides also developed Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBM) that were harder to track and target because they operated beneath the oceans' surface. Between them, the bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs formed what came to be known as the nuclear triad, a joined-up, combined-forces land, sea and air strategy that mirrored the approach to conventional warfare.

The difference, however, was that this was not a strategy designed to win a war, it was designed to prevent one.

What is the concept of MAD?

The idea of a military deterrent can be traced back to Roman times but it wasn't until the Cold War that nuclear weapons unleashed the real potential of this idea.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

At its heart, it had always proposed that the threat of an overwhelming military response could be used as a psychological weapon to dissuade an enemy from attacking. As the Cold War progressed and both sides acquired vast arsenals of nuclear weapons, this concept gained more and more credence.

An ICBM on parade in Moscow during celebrations for the 50th anniversary of the 1917 Revolution

By the mid-1965, the combined US-USSR stockpile of nuclear weapons had grown from 3,000 in 1955 to 37,000. Enough to annihilate their respective populations and eradicate their civilisations several times over.

Rather than call a halt to the production of nuclear weapons the arms race continued unabated amid a doctrine that was named Mutually Assured Destruction. This effectively terrorised each side into keeping the peace, knowing that an act of aggression would ultimately be a suicidal one.

The seismic shifts in technology and the evolving geo-political landscape helped to define what MAD looked like. This resulted in the development of two distinct lines of strategic thinking.

One argued for what was called a 'flexible response' and spoke of the need for nonmilitary and non-nuclear options to be considered in the event of an attack. The other highlighted the need for what was known as a 'second strike capability' and made the case for having the means to respond to a nuclear attack with a retaliatory attack of similar or greater magnitude.

Operation Chrome Dome

By the early 1960s, US intelligence was claiming, wrongly as it turned out, that the Soviets had enough ICBMs to wipe out all of the US' retaliatory capability before a second strike could be launched. In keeping with the logic that had given the world MAD, the US military came up with a solution to this perceived 'missile gap' as it was called.

Operation Chrome Dome was a United States Air Force (USAF) mission that lasted from 1961 to 1968. It saw a never-ending convoy of B-52 bombers armed with nuclear warheads fly in constant rotation just outside Soviet airspace, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

At any given time, there were up to 50 fully armed B-52s in the air, guaranteeing a second strike capability even if a Soviet attack destroyed all of the US' airfields and missile sites.

Sorties typically lasted 24 hours, with planes being refuelled in mid-air, and often took the bombers, and their bombs, over large tracts of the US, Canada and Greenland. With so many sorties being flown, accidents were inevitable.

In total, there were five crashes involving thermonuclear devices including the infamous Goldsboro crash in 1961. The operation was eventually closed down in 1968 after a B-52 crashed into sea ice in North Star Bay, Greenland. The nuclear payload ruptured in the subsequent explosion causing radioactive contamination of the entire area.

A B-52 bomber is refuelled in mid-air by an KC-135 tanker, 1965

Does Mutually Assured Destruction still exist?

Despite several international treaties that sought to curtail the proliferation of nuclear weapons, there were an estimated 70,000 in existence by the time the Cold War ended in 1991.

Today, that number has dropped to around 12,000, although ownership of them has spread. In addition to the US and Russia, the UK, France, China, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea all have nuclear weapons. Because of that, deterrence still plays a vital part in global security and international relations.

Its role, however, has become far more complex, as each of those countries has its own set of deterrent relationships with those nations it views as adversaries.

There are also many other countries, such as Japan, South Korea, and the growing list of NATO states, that are closely allied to the US and therefore enjoy what's called extended deterrence status. In other words, their security is underwritten by the US nuclear capability.

The US is the only nuclear power to do this, leveraging its nuclear arsenal both militarily and diplomatically to extend and maintain its global dominance.

Detonation of the nuclear device code-named 'Badger' during the USA's Operation Upshot-Knothole in 1953

On the cusp of World War Three: Q&A with Roger Hermiston

Roger Hermiston is an historian, journalist and author of several books including Two Minutes To Midnight 1953, The Year of Living Dangerously The following interview originally appeared in History of War issue 106 (published March 2022).

What nuclear capabilities did the West and the USSR respectively reach in 1953 that made that year so significant?

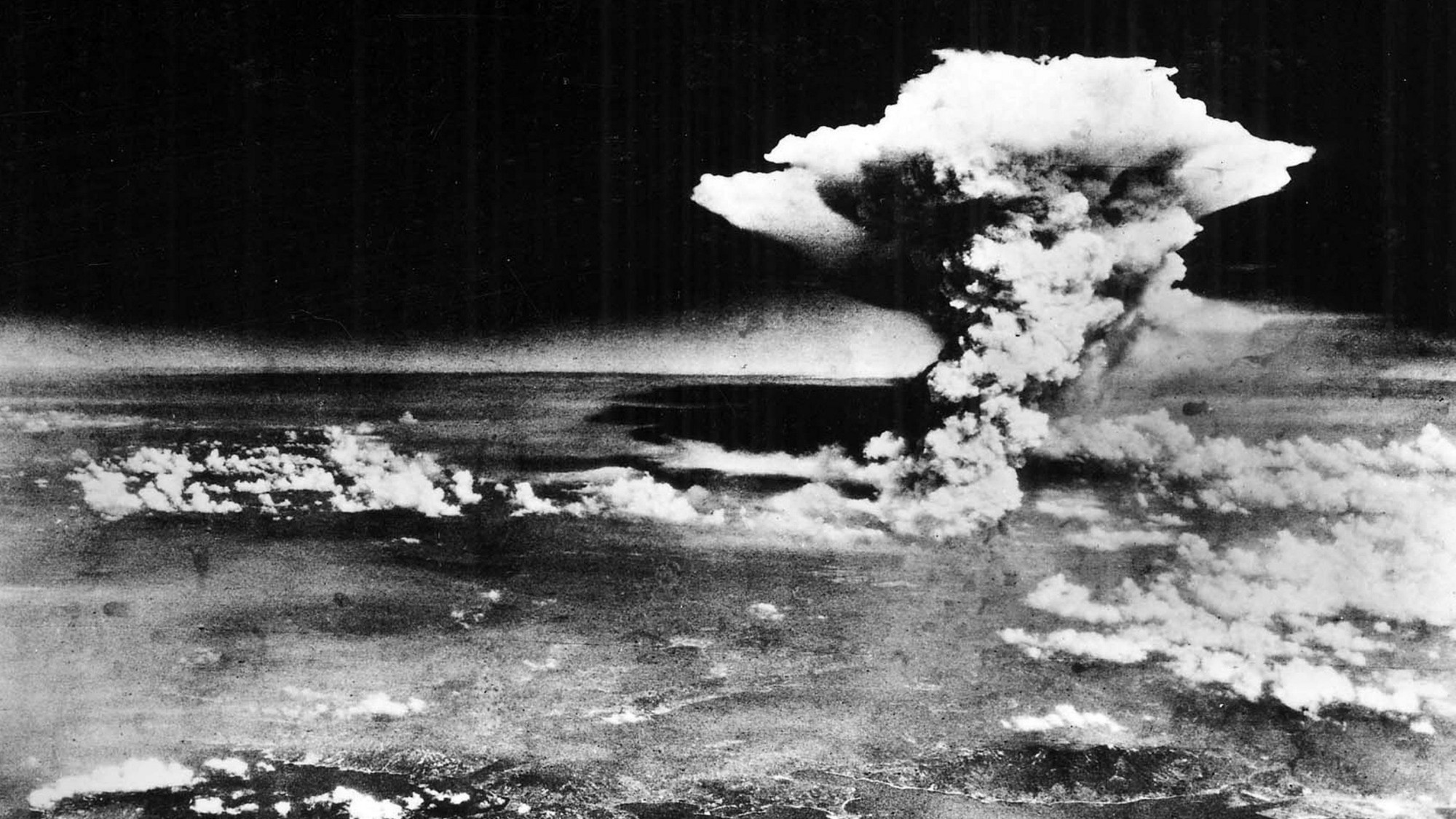

It was the year when the world moved a dangerous step forward from the atom bomb to the new terrifying 'superbomb' – a thermonuclear explosive, based on hydrogen fusion, up to a thousand times more destructive than the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Americans had produced their prototype H-bomb – codenamed Ivy Mike – in November 1952; now the Russians successfully tested their own, codenamed Joe-4, in August 1953. As a result the Doomsday Clock, that measurement of how close the world is to Armageddon, was moved to two minutes to midnight (the closest it had been in seven years of Cold War).

How much did both the White House and the Kremlin know about the other's nuclear capabilities at this time?

Not a huge amount – nowhere remotely what they know today. The Soviets had been well-informed about the American atom bomb by their Western agents, especially Klaus Fuchs, but by 1953 nearly all of them had been uncovered and arrested.

As for the West, when the Iron Curtain came down in 1947 it made it very difficult for their spies to penetrate the Kremlin. It was certainly a surprise to President Dwight Eisenhower's administration when Georgy Malenkov, the new Russian leader, announced to the Supreme Soviet that his country now had the H-bomb.

'Atomic Annie', an 85-ton artillery piece designed to fire a nuclear shell, pictured during tests in the Nevada desert in 1953

When were safeguards put in place between Moscow and Washington to prevent any accidental escalation or nuclear strike?

After the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 President JF Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev set up a 'hotline', providing direct communication between the White House and the Kremlin.

In future years additional safeguards were put in place, including the 1971 Agreement on Measures to Reduce the Risk of Outbreak of Nuclear War and the 1972 Agreement on the Prevention of Incidents at Sea.

How did these safeguards developed during the Cold War and to what extent do they still exist?

Broad safeguards – through reducing the amount of nuclear weapons in circulation – developed through treaties like the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 1987, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) in 1991, and the Strategic Offensive Reduction treaty (SORT) in 2002.

Interestingly, on 3 January 2022 the five big nuclear powers – United States, China, Russia, France and the United Kingdom – signed a joint statement committing themselves to 'Preventing Nuclear War and Avoiding Arms Races'.

President John F Kennedy pictured in the Oval Office consulting with senior military officials during the Cuban Missile Crisis

You write that President Eisenhower considered a preliminary strike during the Korean War. Do we know if he had any specific plans to carry this out?

The idea of using tactical A-bombs on the battlefield to end the Korean War was discussed in seven National Security Council meetings between February and March. It never came too close to fruition, but John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower's Secretary of State, wanted to remove the 'taboo' on the nuclear weapon and view it as simply another weapon in his nation's armoury.

Then, after the Soviets successfully tested their H-bomb in August 1953, Eisenhower, thinking about possible nuclear conflict, pondered "whether or not our duty to future generations did not require us to initiate war at the most propitious moment that we could designate".

Are there any parallels with today's rhetoric regarding nuclear arsenals?

In 1953 the most worrying moments came after the death of Stalin, with the Korean War still raging. There was optimism that we might enter a new era of 'détente' with the Soviets, but the problem was no-one really knew what his successors in the Kremlin were thinking.

Two weeks after Stalin's funeral, the shooting down of a British Lincoln bomber by a Soviet MiG fighter – killing all six crew – was a dangerous flashpoint. Today mutually assured destruction is entrenched and acknowledged, so Vladimir Putin's disturbing rhetoric will remain just that – rhetoric. By attacking the West with nuclear weapons he would invite the destruction of his own country.

This article originally appeared in History of War magazine issues 106 and 138. Click here to subscribe to the magazine and save on the cover price.

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?

Has Putin launched the second nuclear arms race?In Depth Historian Serhii Plokhy explains why the Kremlin’s nuclear proliferation has begun a dangerous new era of mutually assured destruction

-

How Putin misunderstood his past victories

How Putin misunderstood his past victoriesIn Depth Though Vladimir Putin has led Russia to a number of grisly military triumphs, they may have misled him when planning the invasion of Ukraine

-

America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

America's controversial path to the atomic bombIn Depth The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

-

Kinmen Islands: Taiwan's frontline with China

Kinmen Islands: Taiwan's frontline with ChinaIn Depth Just a few miles off the mainland, the Kinmen Islands could be attacked first if China invades Taiwan

-

The origins of the IDF

The origins of the IDFIn Depth The IDF was formed by uniting Zionist paramilitary groups, WWII veterans and Holocaust survivors

-

A brief history of the centuries-old relationship between Ukraine and Russia

A brief history of the centuries-old relationship between Ukraine and RussiaIn Depth The countries are bound together by history and geography, but Putin sees danger in that symbiosis

-

Vladimir Putin’s narrative of Russian victimhood examined

Vladimir Putin’s narrative of Russian victimhood examinedfeature Russian president has repeatedly pointed to his country’s history to justify Ukraine invasion

-

What happened at the Battle of Trafalgar?

What happened at the Battle of Trafalgar?In Depth Monday marks the 214th anniversary of Britain’s most famous naval victory