What happened at the Battle of Trafalgar?

Monday marks the 214th anniversary of Britain’s most famous naval victory

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Attention, holiday hipsters. If Halloween, Christmas or Easter are just too mainstream for you, 21 October will see the UK celebrate one of its lesser-known holidays: Trafalgar Day, which commemorates perhaps the most famous British military victory in history.

Towns up and down the country will this weekend prepare for ceremonies that are taking place on the 214th anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar. The battle, which pitted the outnumbered Royal Navy against the French and Spanish fleets, was a key turning point in the War of the Third Coalition - part of the Napoleonic Wars - and effectively ended France’s status as a naval superpower.

Such was the decisiveness of Britain’s victory at Trafalgar, Royal Navy’s commander, Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson, remains a household name more than 200 years later, and the battle has become an iconic chapter in UK military history.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But what happened at Trafalgar and why was it so important?

Background

The BBC says the groundwork for the battle was laid by the breakdown of the 1803 Peace of Amiens, “a temporary armed truce between Britain and France”. For around two years after the collapse of the agreement, British strategy “rested on the defensive, waiting for the French navy to make the first move”. Finally, late in 1804, Spain joined the war as an ally of France, giving Napoleon the ships he needed to launch a planned invasion of Britain the following year.

Napoleon, according to the Royal Navy website, needed to gain control of the English Channel to allow his Grand Armee to cross over to Britain, and to achieve this he “ordered the French fleet’s three squadrons blockaded at Brest, Toulon and other ports to break out, meet in West Indies and then return as one fleet to gain control of the Channel”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

After Nelson initially gave chase across the Atlantic, the squadron of French Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve at Toulon eventually lost its nerve and - once the British had been blown off course by a storm - took refuge near the Spanish port of Cadiz. From here, it was ideally positioned to attack British trading ships or Britain itself and, according to the BBC, “it had to be destroyed”.

At the end of September 1805, Villeneuve had received orders from Napoleon to leave Cadiz and land troops at Naples to support the French campaign in southern Italy. On 20 October the full Franco-Spanish fleet - consisting of 18 French and 15 Spanish vessels - left Cadiz and attempted to slip through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean Sea without engaging in battle.

Shortly before nightfall the same day, a French ship spotted Nelson’s fleet of 27 vessels in pursuit. They had been caught and prepared for battle overnight.

The battle

Standard naval tactics of the time dictated much of Villeneuve’s preparations for the battle, during which he ordered his fleet to form a single line heading north, although a last-minute change of plans had caused his line to be somewhat crooked and unevenly spaced.

Nelson, however, flipped all traditional orthodoxy on its head with tactics that would effectively change naval warfare for ever. In perhaps one of the riskiest moves in military history, Nelson formed his fleet into two columns for a risky head-on approach.

At 11.50am Nelson, in HMS Victory, signalled his famous message: “England expects that every man will do his duty.” Ten minutes later, the Franco-Spanish fleet opened fire on the British.

Because they were heading directly towards the enemy and their broadsides were facing out into the open sea, the Royal Navy fleet was unable to open fire for over 40 minutes, sustaining heavy fire and losing at least 50 men during this time.

Once the now-concave line of the Franco-Spanish fleet had curled far enough around Nelson’s two columns of ships, he ordered return fire as he cut through the enemy line, shrouding his fleet in smoke and inflicting catastrophic damage on the enemy vessels.

In the ensuing battle, during which the British ships outpaced and outgunned the numerically superior Franco-Spanish fleet, Nelson was shot through the shoulder and spine by a musket bullet from a French ship and was taken below deck.

By 4.30pm, the battle was won. The Franco-Spanish fleet surrendered with the loss of 22 ships and 15,000 men - around half of whom were prisoners of war - while the Royal Navy had not lost a single vessel. Nelson, however, died of his wounds as the battle came to a close, one of around 1,500 British casualties.

His last words are understood to have been “thank God I have done my duty”, followed by “God and my country”.

Legacy

Trafalgar was Britain’s greatest naval triumph, effectively destroying Napoleon’s hopes of invading the UK.

“This had set the limit to Napoleon’s empire, and plotted the course of his downfall,” the BBC says, adding: “Other British admirals could have won at Trafalgar, but only Nelson could have settled the command of the sea for a century.”

In the years that followed, Trafalgar also cemented Nelson’s image as a national hero in the UK, which he remains to this day.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, he had “finally broken the unimaginative strategic and tactical doctrines of the previous century and taught individual officers to think for themselves”.

“Spectacular success in battle, combined with his humanity as a commander and his scandalous private life, raised Nelson to godlike status in his lifetime, and after his death at Trafalgar in 1805, he was enshrined in popular myth and iconography,” the encyclopedia adds. “He is still generally accepted as the most appealing of Britain’s national heroes.”

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

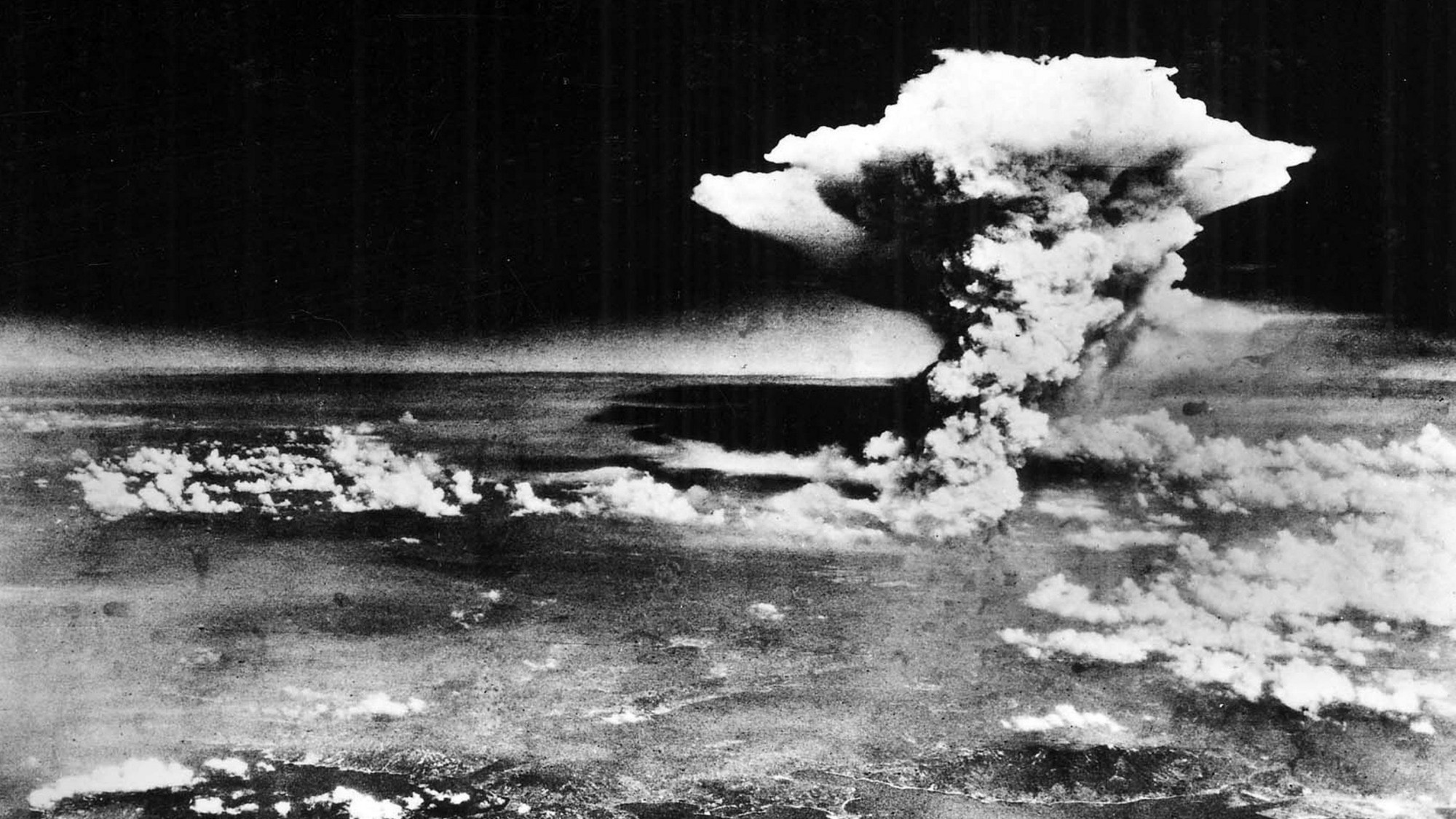

America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

America's controversial path to the atomic bombIn Depth The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

-

Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: colonial roots of the war

Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: colonial roots of the warIn Depth The 2025 clashes originate in over a century of regional turmoil and colonial inheritance

-

Kinmen Islands: Taiwan's frontline with China

Kinmen Islands: Taiwan's frontline with ChinaIn Depth Just a few miles off the mainland, the Kinmen Islands could be attacked first if China invades Taiwan

-

The origins of the IDF

The origins of the IDFIn Depth The IDF was formed by uniting Zionist paramilitary groups, WWII veterans and Holocaust survivors

-

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear Armageddon

Mutually Assured Destruction: Cold War origins of nuclear ArmageddonIn Depth After the US and Soviet Union became capable of Mutually Assured Destruction, safeguards were put in place to prevent World War Three

-

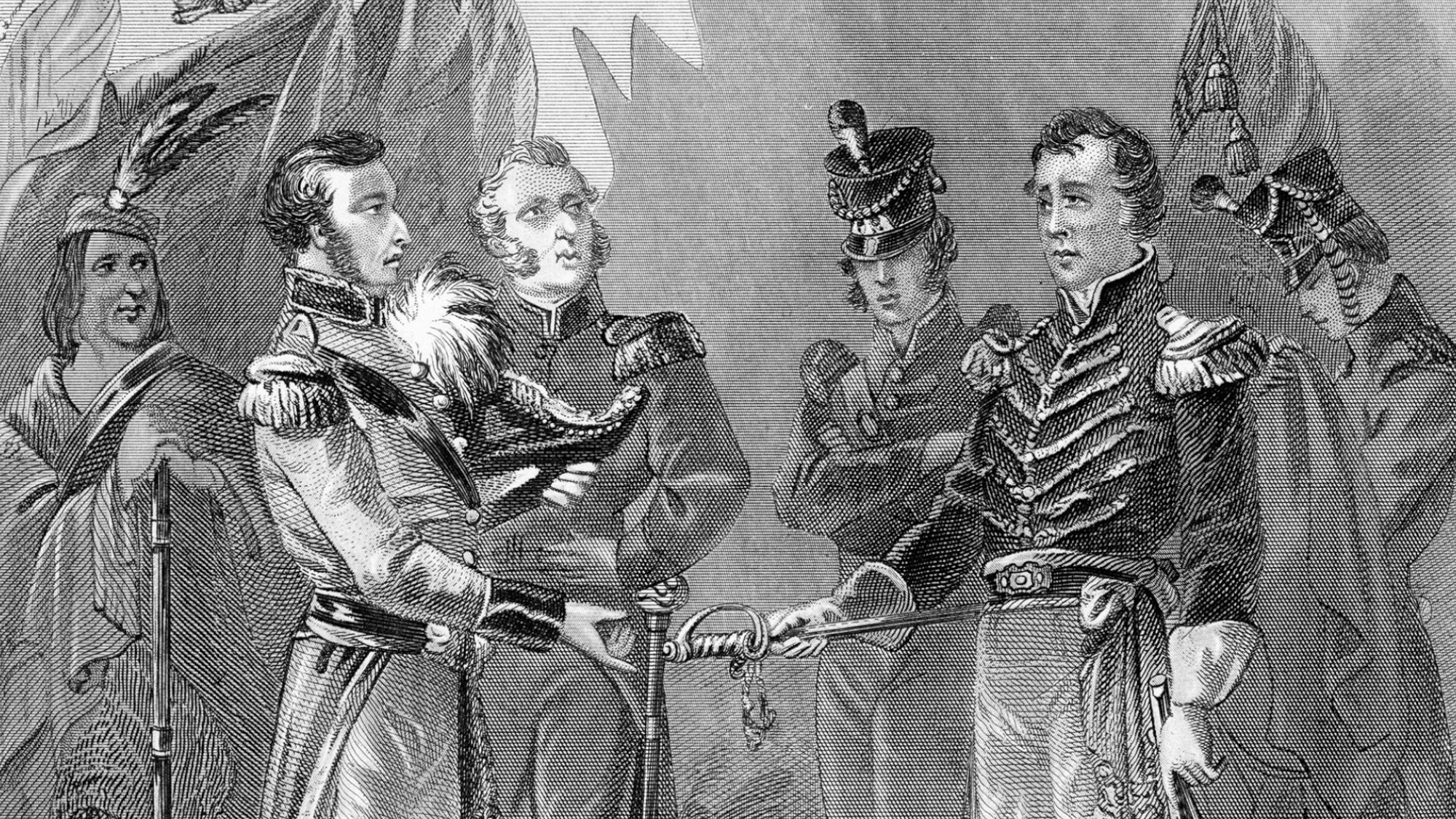

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

When Santa fought for the Union

When Santa fought for the UnionThe Explainer How the bloodshed and turmoil of the Civil War helped make the modern American Christmas.

-

A brief history of human cannibalism

A brief history of human cannibalismfeature Madrid arrest brings focus on historic practice