Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: colonial roots of the war

The 2025 clashes originate in over a century of regional turmoil and colonial inheritance

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article originally appeared in History of War magazine issue 149.

The border clashes between Thailand and Cambodia in July 2025 originate in the region's colonial era over a hundred years ago. At least 12 Thai nationals and an unknown number of Cambodians were killed during the fighting, according to the BBC. The attacks took place in a disputed region known as the 'Emerald Triangle', which lies between Cambodia and Thailand.

The area is home to the Preah Vihear temple complex, a UNESCO heritage site dating back to the 11th century. Tensions between the two countries persisted throughout the 20th century, and was preceded by French and British colonial interests and interventions in southeast Asia. Tensions on the border escalated during the chaotic periods of the Vietnam War, Cambodian–Vietnamese War, and the Khmer Rouge dictatorship.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Origins of the Thailand-Cambodia dispute

In the early 20th century Thailand was still known as Siam, a kingdom that while under economic control of the British Empire and its unstoppable merchant fleet, had largely preserved its independence. The kingdom spent decades refashioning itself into a modern state, aided in the process by treaties with England and France that agreed on lasting borders.

Having formulated the borders of Indo-China (Vietnam) from the mid-19th century onward, France also wrangled distant Siamese provinces with treaties in 1904 and 1907. Similar arrangements were settled with the British in 1909, which ended years of incursions from the Malayan peninsula, as well as from Burma (Myanmar) in the northwest.

After renaming itself Thailand in 1939, modernisation progressed with the usual characteristics of Southeast Asian countries – foreign investment and centralised government – helped along by the country's location. Its capital Bangkok not only flourished at the mouth of a river delta but also had access to a vast gulf.

Thai army soldiers secure the grounds of a venue in Bangkok, for peace talks between pro- and anti-government groups. May 22, 2014

The country's interior was neatly bracketed by dense forest and mountains, leaving uninterrupted wetlands suited for large-scale rice cultivation. These advantages gave its borders paramount importance, even during the Second World War. The non-aligned Thai state fought Vichy forces in 1940 in a sudden rebuke to decades of amity.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

With as many as a dozen coup d'etats sweeping its government since the 1930s Thailand's democratic tradition is unchanged today: civilian leadership in name only, while former generals enjoy important government positions with the monarchy's blessing. This age-old problem metastasised as the Cold War loomed over Southeast Asia.

By the 1960s, Bangkok's pseudo-military junta, where former generals monopolised the civilian high offices with the explicit backing of the monarch, eagerly joined any arrangement to keep the ongoing war in Vietnam at bay. This meant the unfailing support and largess of the United States.

Cambodian soldiers at a military base, preparing to go to Preah Vihear temple in Preah Vihear province, February 6, 2011

Thailand was also briefly a member of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and managed to shape the newly minted Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) regional bloc that brought it in league with Indonesia, a country that swayed from one alliance to the next depending on its leaders' calculations.

But the 1970s and the victory of North Vietnam in 1975, as well as communists seizing Laos and Cambodia that same year, unravelled Thailand's hedging. By the middle of that decade a refugee crisis almost overwhelmed its eastern provinces as exiles from Cambodia and the fallen Republic of Vietnam arrived by any means necessary.

Isolated and enjoying diplomatic support from China, the murderous Khmer Rouge regime that dominated Cambodia was now a heavily armed menace, and the Thai army had the thankless task of keeping them at bay.

Young guerrillas celebrate the capture of the Cambodian capital, Phnom Penh, to the Khmer Rouge, April 17, 1975.

Cambodian–Vietnamese War

In 1979 Vietnam launched a surprise invasion of Cambodia, which created another refugee crisis and replaced the challenge of an unstable regime with a Vietnamese occupation now on Thailand's doorstep.

Just as in the early 20th century, Bangkok preserved its strength and sought compromise. With a communist rebellion snuffed out through amnesty and cash handouts in 1982, heartfelt diplomacy with China became essential.

The re-emergence of a viable Cambodian state in the late 1990s and its modest prosperity was not the godsend Thailand needed. Having grown to the second-largest economy in the region and with its political fault lines unresolved, Bangkok had the twin headaches of rampant drug trafficking on the Myanmar border and a post-war refugee crisis on the Cambodian border.

Refugees travelling to the Thailand border, fleeing the Vietnamese invasion, 1979

The independence of the kingdom once known as Kampuchea, later subsumed by French colonialism in the late 19th century, always left endangered borders where rebellion and illicit trade flourished. The risk was always too great for Bangkok to withstand, whether in the primacy of the Chakri kings or today's thinly veiled junta, so the occasional show of force was almost inevitable.

Successive prime ministers cultivated their counterparts in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, including the affable and nepotistic Hun Sen (his son has since replaced him), but the lingering question of the border remained, especially in the romanticised 'Emerald Triangle'.

While neither country sees the status of their border and its landmarks as existential — both have an abundance of arable land blessed by fair weather all year round — the stark ruins of heritage sites like the Preah Vihear temple complex become flash points because of overzealous border policing.

A Cambodian soldier walks past Preah Vihear temple, near the Thai border in the Cambodian province of Preah Vihear, July 21, 2008

The 2025 border clash

The Royal Thai Armed Forces have sought to contest the 'emerald triangle' region several times in 30 years but have never launched a full-scale war. Prudence has often prevailed because the army is preoccupied with domestic politics in an affluent society.

If revisionism were the cause of the border dispute, it is a very mellowed-down version as neighbouring countries in the ASEAN bloc insist on mediation.

The problem endures as the modern statehood of Cambodia and Thailand demands that present borders be revised, with the view from Phnom Penh favouring international court rulings while Bangkok prefers the historical approach of bilateral agreements. The Thais are sticking to their successful compromises with colonial powers and Cold War rivals.

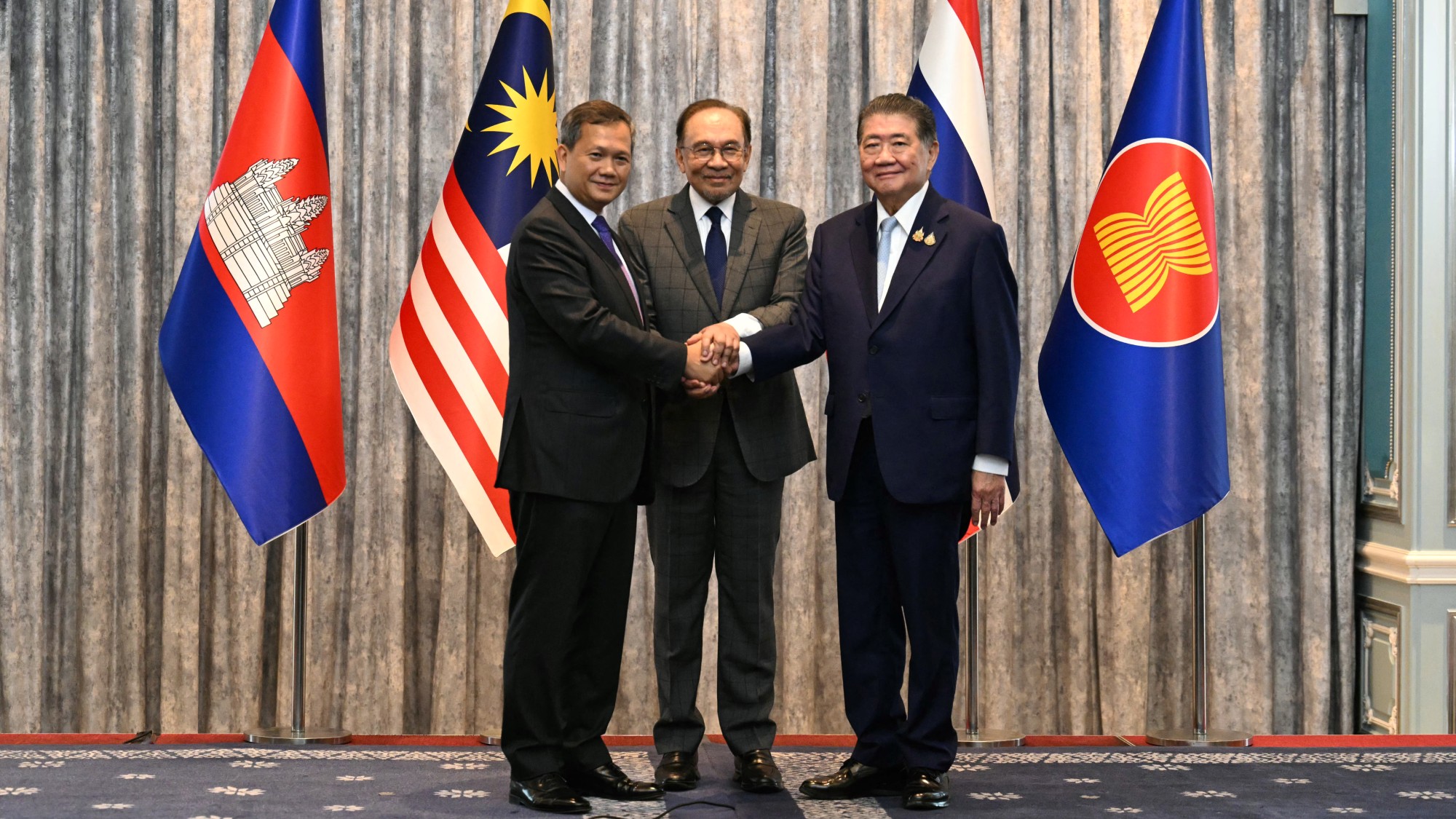

Malaysia's Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim (C), Cambodia's Prime Minister Hun Manet (L) and Thailand's acting Prime Minister Phumtham Wechayachai (R) at the ceasefire conference, July 28, 2025

When cross-border artillery duels erupted in the middle of 2025 the almost quarter-million Cambodian and Thai civilians who fled for their lives hastened a summit organised by Malaysia over a weekend.

When a smiling Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim eventually settled the conflict with vague promises and glowing news coverage it seemed the world breathed a sigh of relief. At the very least, the worst was averted for a time.

This article originally appeared in History of War magazine issue 149. Click here to subscribe to the magazine and save on the cover price!

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

The curious history of hanging coffins

The curious history of hanging coffinsUnder The Radar Ancient societies in southern China pegged coffins into high cliffsides in burial ritual linked to good fortune

-

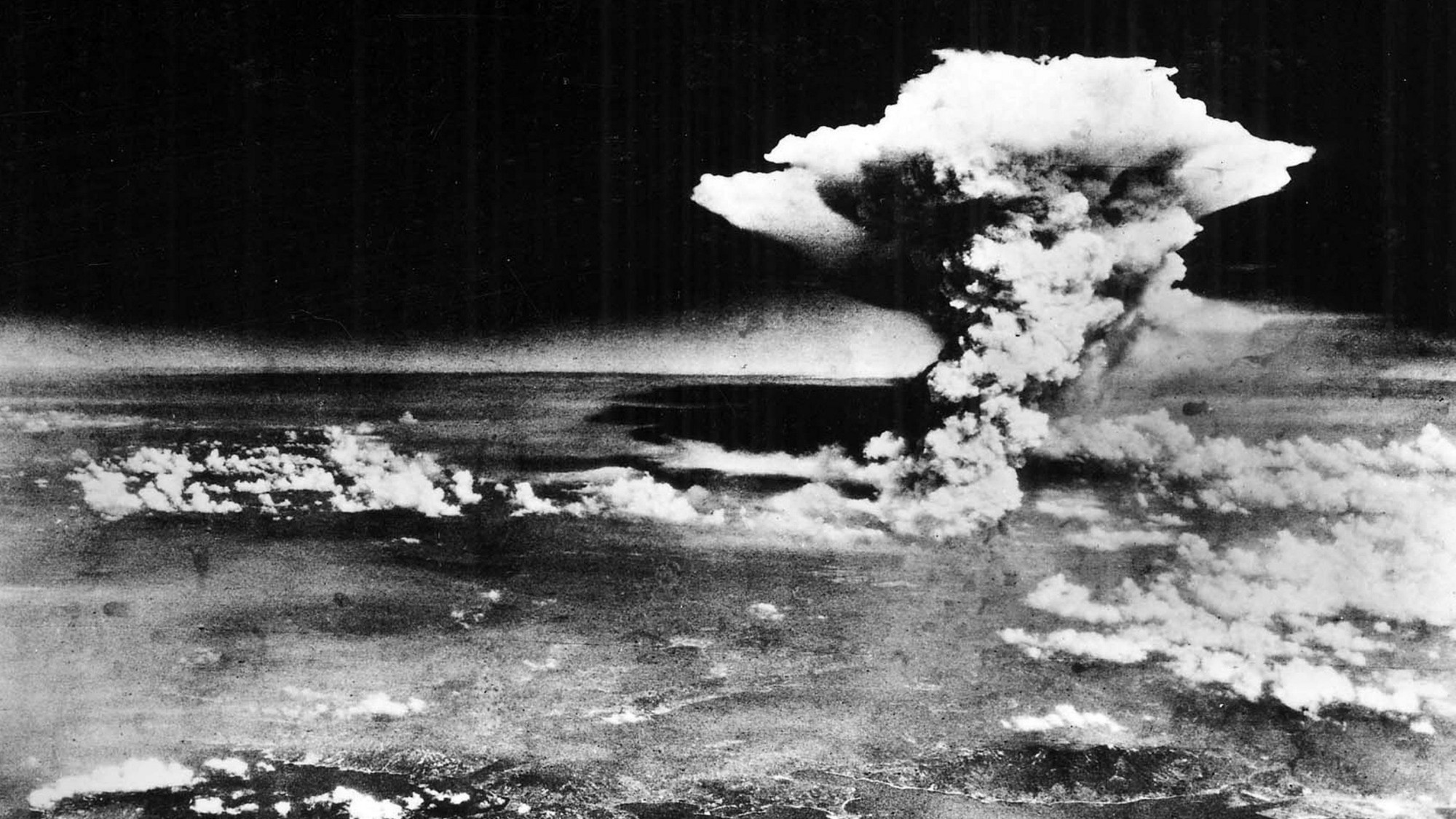

America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

America's controversial path to the atomic bombIn Depth The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

-

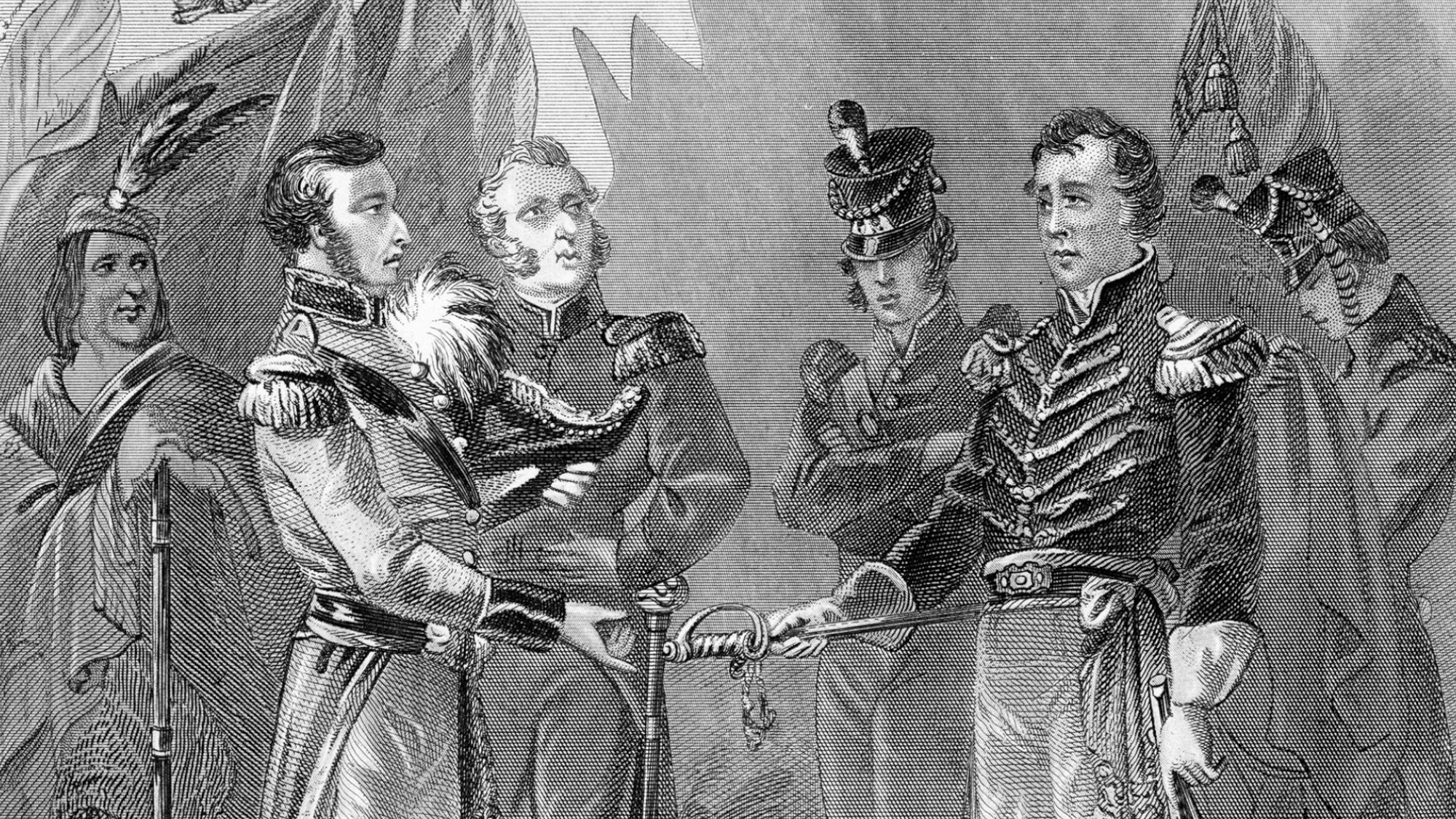

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

When Santa fought for the Union

When Santa fought for the UnionThe Explainer How the bloodshed and turmoil of the Civil War helped make the modern American Christmas.

-

What happened at the Battle of Trafalgar?

What happened at the Battle of Trafalgar?In Depth Monday marks the 214th anniversary of Britain’s most famous naval victory

-

What do the different coloured poppies symbolise?

What do the different coloured poppies symbolise?In Depth Volunteers are distributing millions of poppies in the run up to Remembrance Day

-

The secret history of the gay soldiers who served in the First World War

The secret history of the gay soldiers who served in the First World WarIn Depth Discrimination and persecution has led to gay soldiers of the Great War being seen as tragic figures, but this was not always the case

-

How did World War One end?

How did World War One end?In Depth Duchess of Cornwall marks Armistice Day at Westminster Abbey