How did World War One end?

Duchess of Cornwall marks Armistice Day at Westminster Abbey

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Each year on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month, Britain comes together to commemorate those who died in military conflicts.

A two-minute silence is held annually on Armistice Day, which marks the end of World War One in 1918. People also wear pins shaped like poppies, the symbol of remembrance, to pay tribute to fallen soldiers and support the Royal British Legion.

This year’s ceremony was led by Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, who laid a custom-made wooden cross amid the poppies at the 93rd Field of Remembrance outside Westminster Abbey.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Historically Prince Philip, who died in April this year, led the Armistice Day ceremony on behalf of the Royal Family. The Queen was not present at this year’s event, but she has said that it is her “firm intention” to attend the Remembrance Sunday service at the Cenotaph this weekend, the BBC reported.

Delegates at the Cop26 climate summit in Glasgow, including Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon and UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, took part in a two-minute silence led by Cop President Alok Sharma.

Last year’s ceremonies were reduced in scale as they fell during the UK’s second national lockdown. Prince Charles, Camilla, Boris Johnson and Keir Starmer came together for a socially distanced Westminster Abbey ceremony, but the general public mostly marked the occasion at home, with many standing on their doorsteps to observe the two-minute silence.

The start of the First World War is considered to have been triggered by the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand - but how did the Great War end?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Russian defeat

In December 1917, the Central Powers signed an armistice with Russia, which was in the midst of a revolution that precipitated its withdrawal from the conflict. This freed large numbers of German troops for use on the Western Front, and for a while the Central Powers looked likely to win the war.

However, that same year, two years after the sinking of the passenger ship the RMS Lusitania by German forces, US President Woodrow Wilson bowed to intense public pressure and officially declared war on Germany.

The Germans were galvanised by a sudden burst of reinforcements on the Western Front after Russia’s defeat in the East. However, with American troops pouring into Europe, they realised that they did not have much time and pushed for a final quick offensive to secure victory.

Failure of Operation Michael

The turning point of the final stages of the war, according to the BBC, was the Spring Offensive, one of the final major German offensives against the Allies.

In an attempt to overwhelm the Allied forces before the material resources of the United States could be fully deployed, the Germans attempted to push through the Allied lines along the Western Front in a series of attacks codenamed Georgette, Gneisenau, Blucher-Yorck and Michael.

Operation Michael was the largest of these offensives, and drove the Allies back across the wilderness left by the devastating Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Although the next stage was to push the French and British armies back to the English Channel and force them off the European mainland, the German advance across the Somme had been costly for the Central Powers, that any attempts to advance further were futile.

The French and British armies held firm in France, awaited US reinforcements, and on 8 August 1918 commenced the Hundred Days Offensive - a series of devastating and decisive counter-attacks that pushed the Germans back into Central Europe.

Armistice

By the autumn of 1918, Germany and its allies were exhausted. Their armies were defeated and their hungry citizens were beginning to rebel, said the Imperial War Museum.

Despite this, the German Navy was ordered to sea on 24 October to battle the British. However, the thought of being sent on another deadly offensive when the war was all but lost sparked a mutiny among the soldiers. Unrest started in the town of Kiel in northern Germany, and by 7 November many of the major ports along the German coast were in revolt against the German government.

Germany’s major allies had given up and were already beginning to make peace with the Allies, with Austria-Hungary signing their own armistice on 3 November. Turkey had done the same on 30 October and Bulgaria had surrendered on 30 September.

Realising that even their own soldiers had turned against them, the German government approached the United States with a request for an armistice, which was signed on 11 November 1918, bringing the war to an end.

Aftermath

On 28 June 1919, the UK, US, France, Italy and Japan - known as the League of Nations - signed the Treaty of Versailles along with Germany, a document which remains one of the most contentious in history.

With the Treaty, the League of Nations forced enormous financial, territorial and political concessions from Germany, including the abdication of its kaiser and reparation payments in the order of tens of billions of pounds in today’s money. It also controversially contained a provision that required “Germany [to] accept the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage” during the war.

The subsequent collapse of the Weimar Republic’s economy under the reparation costs “provided a rich material for Adolf Hitler to use to gain the support of those on the right”, said ThoughtCo, creating a political movement dictated by resentment and vengeance that precipitated the rise of Nazism.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

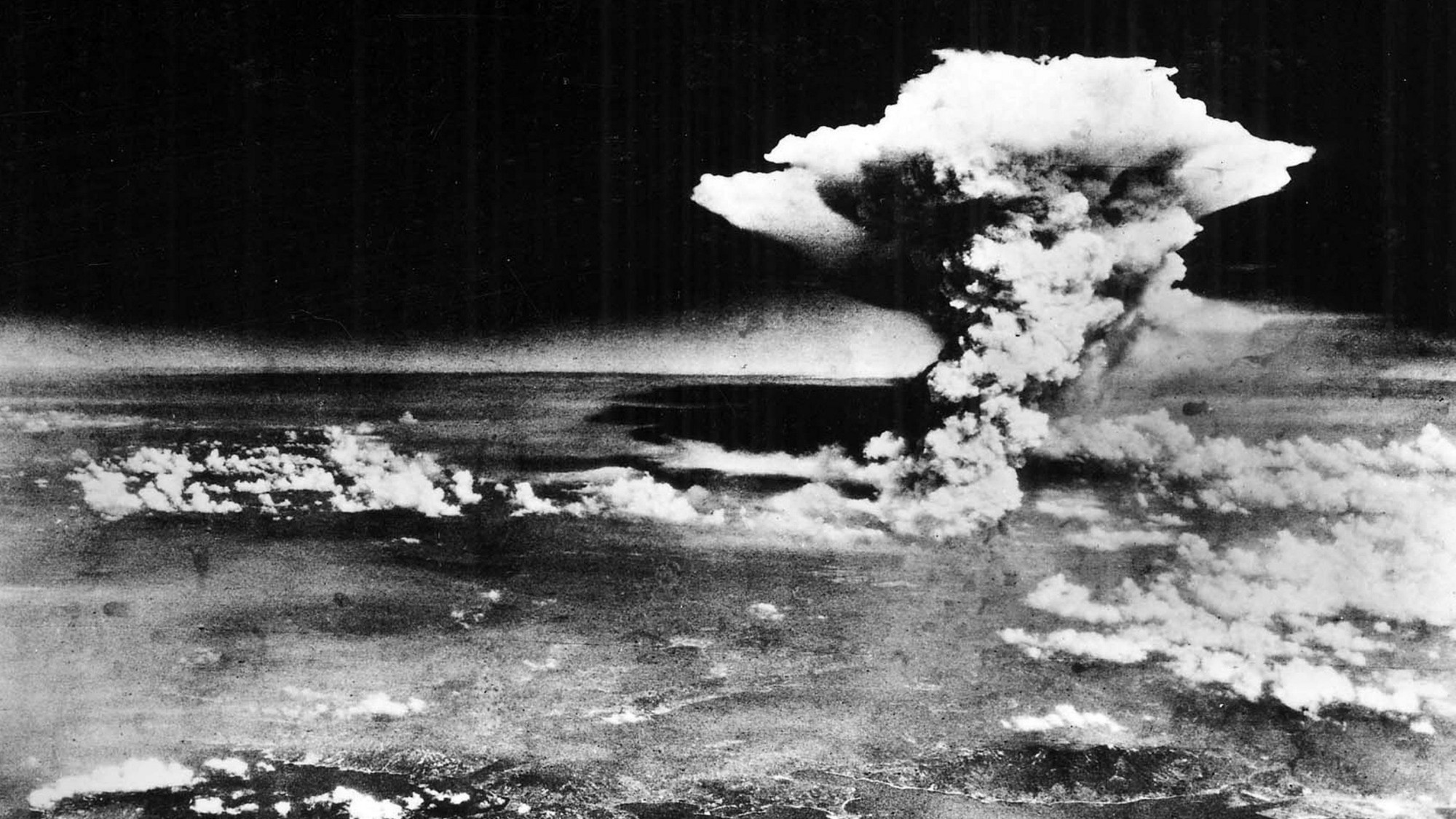

America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

America's controversial path to the atomic bombIn Depth The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

-

Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: colonial roots of the war

Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: colonial roots of the warIn Depth The 2025 clashes originate in over a century of regional turmoil and colonial inheritance

-

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

Namibia grapples with legacy of genocide on Shark Island

Namibia grapples with legacy of genocide on Shark IslandUnder the radar A non-profit research agency believes it has located sites of unmarked graves of prisoners

-

When Santa fought for the Union

When Santa fought for the UnionThe Explainer How the bloodshed and turmoil of the Civil War helped make the modern American Christmas.

-

98-year-old charged with accessory to murder during Holocaust

98-year-old charged with accessory to murder during HolocaustSpeed Read

-

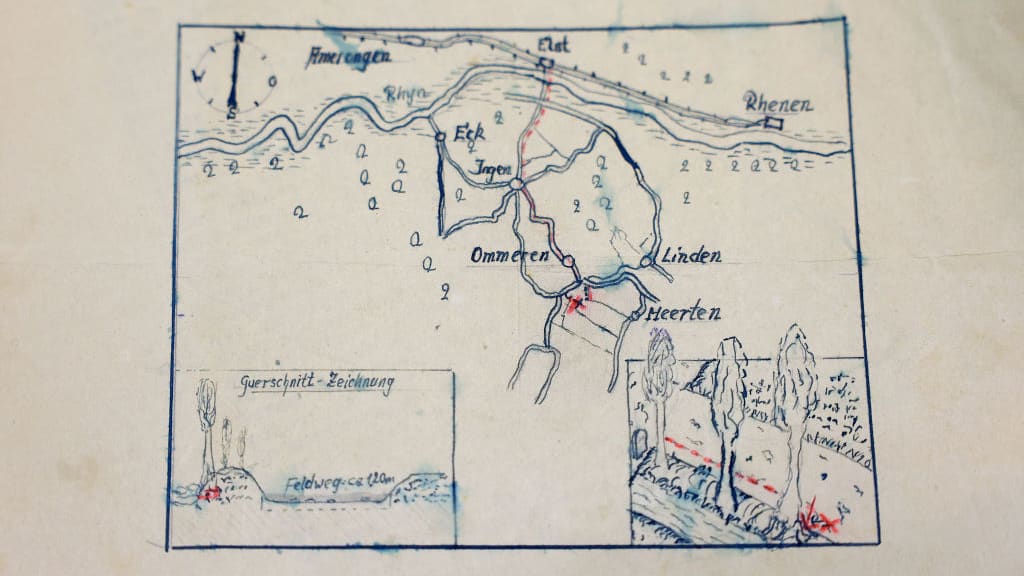

WWII-era map leads to Dutch treasure hunt

WWII-era map leads to Dutch treasure huntSpeed Read

-

Seven tragic Second World War poems

Seven tragic Second World War poemsIn Depth Less well-known than those of the First World War, the poems of WWII are just as gut-wrenching