Namibia grapples with legacy of genocide on Shark Island

A non-profit research agency believes it has located sites of unmarked graves of prisoners

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Namibia is being urged to pause its plans to extend a port on Shark Island, a key site in its genocide and the likely location of human remains.

When the southwest African nation was under German colonial rule, nearly 100,000 indigenous people were killed or died during what is widely recognised as one of the 20th century's first genocides. Between 1905 and 1907, the German empire used Shark Island as a "concentration camp", said The Guardian.

A non-profit research agency believes it has located sites of unmarked graves of prisoners who died there. Authorities are planning to expand the port of what is now a peninsula, but there is a "credible" risk that human remains could be found in the water, said Forensic Architecture.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What is the history?

At the start of the 20th century, tensions escalated between indigenous Herero and Nama people and German settlers, in what was then known as German South West Africa.

In 1904, chief Samuel Maharero led the Herero people in a revolt against exploitation and land appropriation by the Germans. In the same year, Namibia's Nama people also staged an uprising.

German authorities under General Lothar von Trotha unleashed a brutal retaliation, fuelled by racial ideology and including mass killings, forced labour and concentration camps. The massacre is "widely recognised as an intentional extermination attempt", said Al Jazeera. By the time all the camps were shut in 1908, about 80% of the Hereros and about half of the Nama population had died, said Al Jazeera

Near the coastal town of Lüderitz, Shark Island became "synonymous" with the atrocities, said The Namibian. It was modified into a peninsula in 1906 and used as a prison, where inmates were subjected to "starvation, rape, forced labour and beatings".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Unsanitary conditions caused deaths from otherwise preventable diseases, "effectively turning Shark Island into an extermination camp". The island would provide "a blueprint" for Nazi Germany's concentration camps during the Holocaust.

About 3,000 to 4,000 people are thought to have been killed in the camp. Historical accounts suggest their bodies were "thrown to the sharks", according to Forensic Architecture.

In 2019, the Namibian government declared Shark Island a national heritage site, and the Nama people still consider it sacred. But the peninsula is now a tourist site with camping facilities and resorts – and a busy port.

Germany formally acknowledged the genocide in 2021, and pledged £1 billion to Namibia in development aid projects – which was rejected.

What's the latest?

Namibian authorities have proposed expanding the port on Shark Island, to support green hydrogen production and export to Europe by a German company, Hyphen.

Namibia has "abundant sunlight and access to the sea", said Voice of America, making it a potential green hydrogen spot. But some locals view the plan as "a new form of colonisation, where African resources are extracted for the benefit of European markets".

Forensic Architecture is gathering evidence to support calls by Nama and Herero people for direct reparations for the genocide. The group used ground radar to detect anomalies in the soil to identify "mass graves", said The Guardian.

The group published its discovery in April and is calling for a "moratorium on all development projects in the area" until human remains and potential graves are investigated, and the sites fully protected.

Construction would "further desecrate and compromise Shark Island as a site of archaeological, historical and cultural heritage", said Agata Nguyen Chuong of Forensic Architecture.

"Shark Island is a sacred place," said Paul Samuel Herero, Samuel Maharero's great-great-grandson. "We want our people to be able to come and understand the pain and suffering of our forefathers, who died a very painful death. Yet 34 years after independence, my forefathers are still yearning, pleading and begging for recognition with the new Namibia."

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animals

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animalsUnder the Radar A human skeleton definitively shows damage from a lion's bite

-

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

Newly publicized Dutch archives force families to confront accusations of Nazi collaboration

Newly publicized Dutch archives force families to confront accusations of Nazi collaborationUnder the Radar The archives were available to researchers but only recently became publicly accessible

-

The real story behind the Stanford Prison Experiment

The real story behind the Stanford Prison ExperimentThe Explainer 'Everything you think you know is wrong' about Philip Zimbardo's infamous prison simulation

-

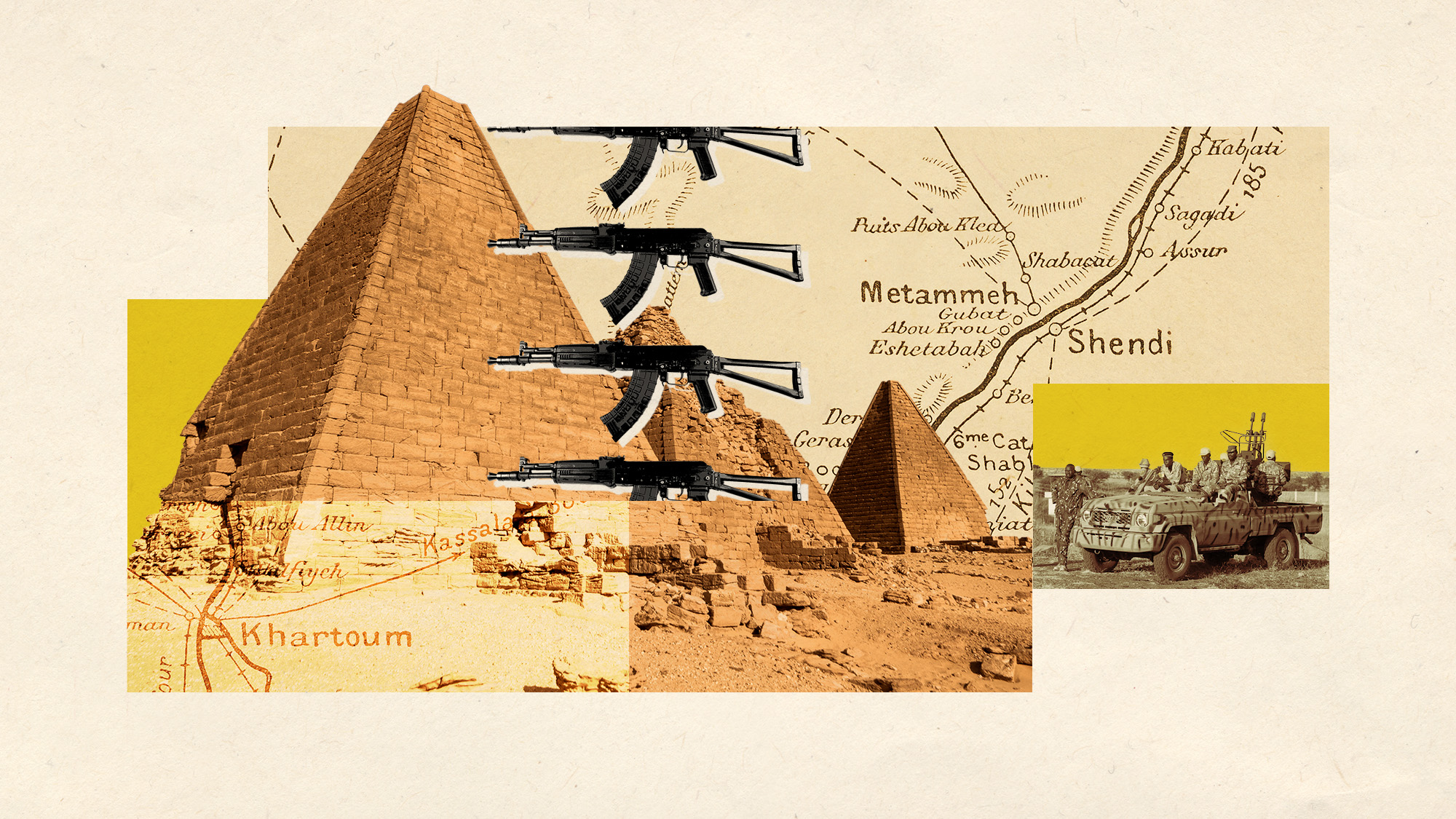

Sudan's forgotten pyramids

Sudan's forgotten pyramidsUnder the Radar Brutal civil war and widespread looting threatens African nation's ancient heritage

-

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raid

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raidSpeed Read She was the first woman to oversee an American military action during a time of war

-

Two ancient cities have been discovered along the Silk Road

Two ancient cities have been discovered along the Silk RoadUnder the radar The discovery changed what was known about the old trade route

-

Stonehenge: a transformative discovery

Stonehenge: a transformative discoveryTalking Point Neolithic people travelled much further afield than previously thought to choose the famous landmark's central altar stone