Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animals

A human skeleton definitively shows damage from a lion's bite

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Historians have long believed that ancient humans fought animals in arena battles, but no definitive evidence has been found — until now. An archeological breakthrough two decades in the making has provided the first proof that gladiators did indeed fight animals.

The discovery by a team of archaeologists may simply confirm what historians have already assumed. But some in the scientific community are hoping the unearthing may continue to unlock ancient secrets.

What discovery was made?

The discovery is the "first physical evidence for human-animal gladiatorial combat," according to the findings, which were published April 23 in the journal PLOS One. The findings came in the "form of a skeleton from a Roman settlement in Britain," said The New York Times. This damaged skeleton was found in the city of York, England, 20 years ago, but archeologists have only now proven what caused the injuries.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This skeleton had "small indentations in the hip bones," said the Times, and these "notches looked like bite marks from a large animal, perhaps a lion." But no proof of this was found when the skeleton was originally excavated. So researchers "created a map of the dimensions and depth of the animals' bites." They then "compared the bite marks left by the different animals with the indentations on the ancient skeleton," which confirmed that the marks came from a lion.

Why is this discovery important?

It is "rare for archaeologists to find physical evidence of such combat in the form of Roman gladiators' remains," especially for "something seemingly so well-documented," said Scientific American. Also, this new evidence "not only offers fascinating clues into the culture of gladiatorial combat but also highlights the astonishingly far-reaching influence of the Roman Empire."

These fights were "one of the key ways that Roman culture was spread," Anna Osterholtz, a bioarchaeologist at Mississippi State University, said to Scientific American. The games "taught things like social roles and social norms." The remains also describe "people's lives that weren't considered important enough to be written down, that were never part of the official record."

The findings, additionally, are proof the U.K. "was well integrated into the customs and systems of the Roman Empire at its peak and provide evidence that Roman entertainments were widespread across the empire," Jaclyn Neel, an associate professor of Greek and Roman studies at Canada's Carleton University, told CNN.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This revelation now opens the door for scientists to make more discoveries — mainly, how these animals may have been transported. Scientists "know that these events happened in the provinces of the Roman Empire, but it raises other questions," Tim Thompson, an anthropologist at Ireland's Maynooth University and the lead author of the study, said to The Guardian. How do you "get a lion from Africa to York?"

Either way, experts seem excited by the prospect of continued research. The realization "gives us a remarkable insight into the life — and death — of this particular individual and adds to both previous and ongoing genome research," David Jennings, the CEO of York Archaeology, said in a press release. Scientists "may never know what brought this man to the arena where we believe he may have been fighting for the entertainment of others," but it is "remarkable that the first osteoarchaeological evidence for this kind of gladiatorial combat has been found so far from the Colosseum of Rome."

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?

Are Big Tech firms the new tobacco companies?Today’s Big Question Trial will determine if Meta, YouTube designed addictive products

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Homo floresiensis: Earth’s real-life ‘hobbits’

Homo floresiensis: Earth’s real-life ‘hobbits’Under the Radar New research suggests that ‘early human pioneers’ in Australia interbred with archaic species of hobbits at least 60,000 years ago

-

Mendik Tepe: the ancient site rewriting human history

Mendik Tepe: the ancient site rewriting human historyUnder The Radar Excavations of Neolithic site in Turkey suggest human settlements more than 12,000 years ago

-

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025The Explainer From prehistoric sunscreen to a brain that turned to glass, we've learned some surprising new facts about human history

-

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

Newly publicized Dutch archives force families to confront accusations of Nazi collaboration

Newly publicized Dutch archives force families to confront accusations of Nazi collaborationUnder the Radar The archives were available to researchers but only recently became publicly accessible

-

Tutankhamun: the mystery of the boy pharaoh's pierced ears

Tutankhamun: the mystery of the boy pharaoh's pierced earsUnder the Radar Researchers believe piercings suggest the iconic funerary mask may have been intended for a woman

-

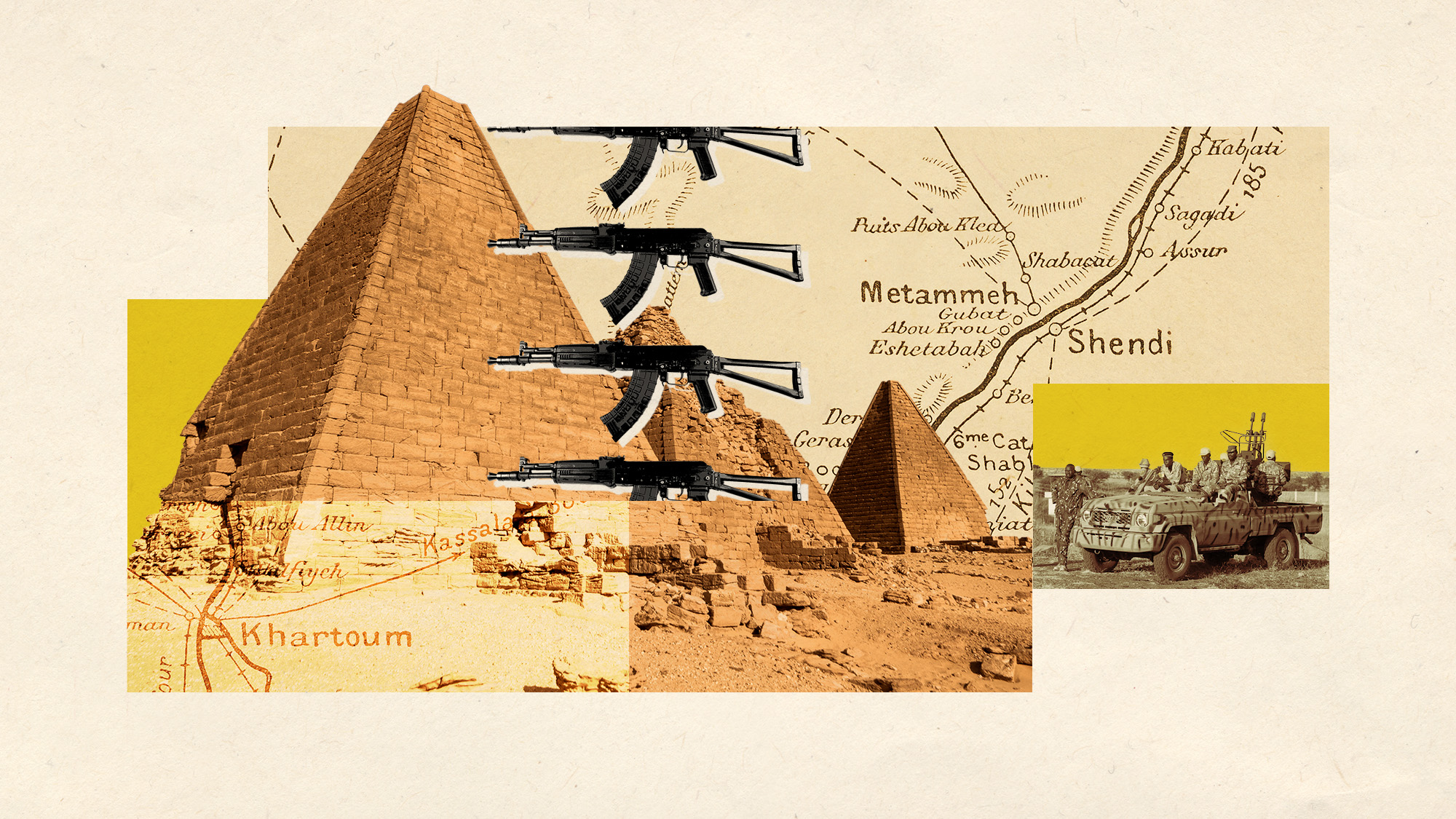

Sudan's forgotten pyramids

Sudan's forgotten pyramidsUnder the Radar Brutal civil war and widespread looting threatens African nation's ancient heritage

-

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raid

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raidSpeed Read She was the first woman to oversee an American military action during a time of war