Newly publicized Dutch archives force families to confront accusations of Nazi collaboration

The archives were available to researchers but only recently became publicly accessible

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A massive trove of historic World War II documents has been unveiled, and it strikes at the heart of a generational issue in the Netherlands. On Jan. 2, the Dutch Central Archives of the Special Jurisdiction was publicly opened under the country's national archive rules. This archive contains information about 425,000 Dutch people who were accused of collaborating with the Nazis during the second world war.

These archives have been available to researchers for the past 70 years, but this marks the first time that members of the public can view their contents. It is estimated that the full portfolio of the Central Archives will be digitally accessible by 2027, according to the archive's website; for now, those wishing to see the documents must visit the physical archive in The Hague. Some descendants of those accused of Nazi collaboration say they are wary of what this public access might mean.

What do these archives contain?

The archive's pages measure about 2.3 miles long and are the "largest and most frequently consulted World War II archives in the Netherlands," said a press report. The pages contain "files about individuals suspected of collaboration with the German occupiers" during World War II, as well as information on "victims, resistance activities, hiding operations and much more."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The 32 million documents include information on Dutch people who were both tried as Nazi collaborators and those who were only suspected of such. This is what largely separates the Dutch archives from similar databases in other European countries. The "entire archive has been preserved, including people who were not convicted, only accused," Tom de Smet, the director of Archives, Services and Innovation at the Dutch National Archives, said to The New York Times. Once the files are digitized online, people will be "able to type in the name of a victim and discover who was accused of betraying them."

How are the Dutch responding?

Some descendants of the accused, as well as the Dutch government, are reportedly concerned over the publication of family histories, especially for those who were only accused. According to the Central Archives, only about a fifth of the people accused of collaboration were ever charged in court.

It is "a bit uncomfortable," Connie, whose family is in the archive, said to The Guardian. She does not "know what could come out of it eventually, if people Google our surname." But others believe that publicizing the archives will help the Netherlands heal from its connection with the Holocaust. The country is "only now coming to terms with" its role in the genocide, said The Guardian.

It is "part of the repression by the Dutch of their memories of collaboration, after we had punished our military and political collaborators," Johannes Houwink ten Cate, an emeritus professor of Holocaust studies at Amsterdam University, said to The Guardian. It is easy to "understand the children and grandchildren of collaborators now fear possible consequences, but my personal experience is that their feelings come to rest once they have seen the files. Making this open is an important step."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Officials are also taking steps to "digitize the files more carefully and slowly, because this is very sensitive for relatives of collaborators," according to Dutch newspaper Trouw. The archive will digitize the most well-known files first, including "more serious cases such as the betrayal of several people in hiding or the murder of resistance fighters, which made the newspapers." Archivists "arrived at this after discussions with the ethical council, which includes relatives of both collaborators and war victims," Edwin Klijn, the leader of the project, said to Trouw.

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animals

Scientists have found the first proof that ancient humans fought animalsUnder the Radar A human skeleton definitively shows damage from a lion's bite

-

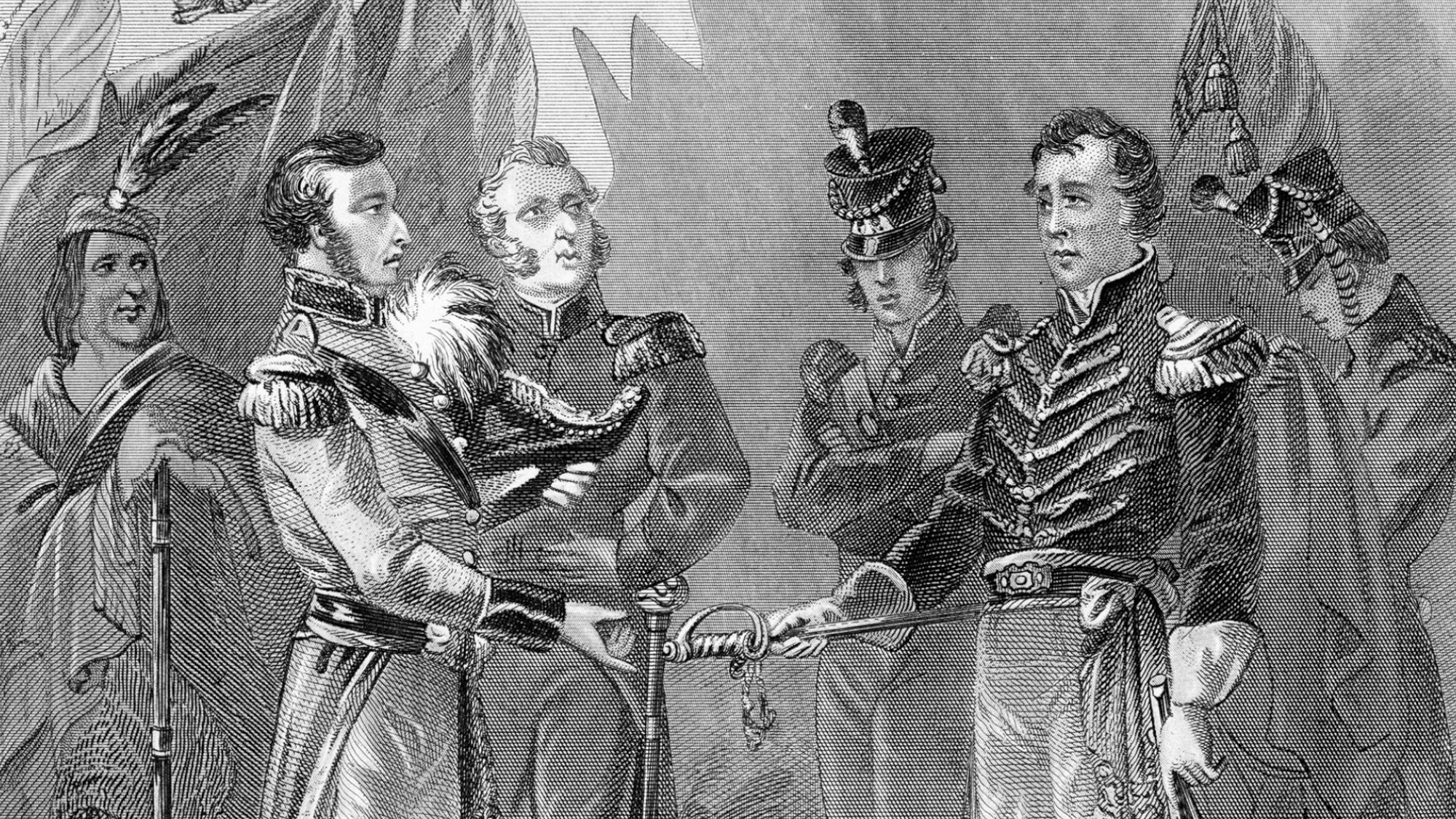

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.

-

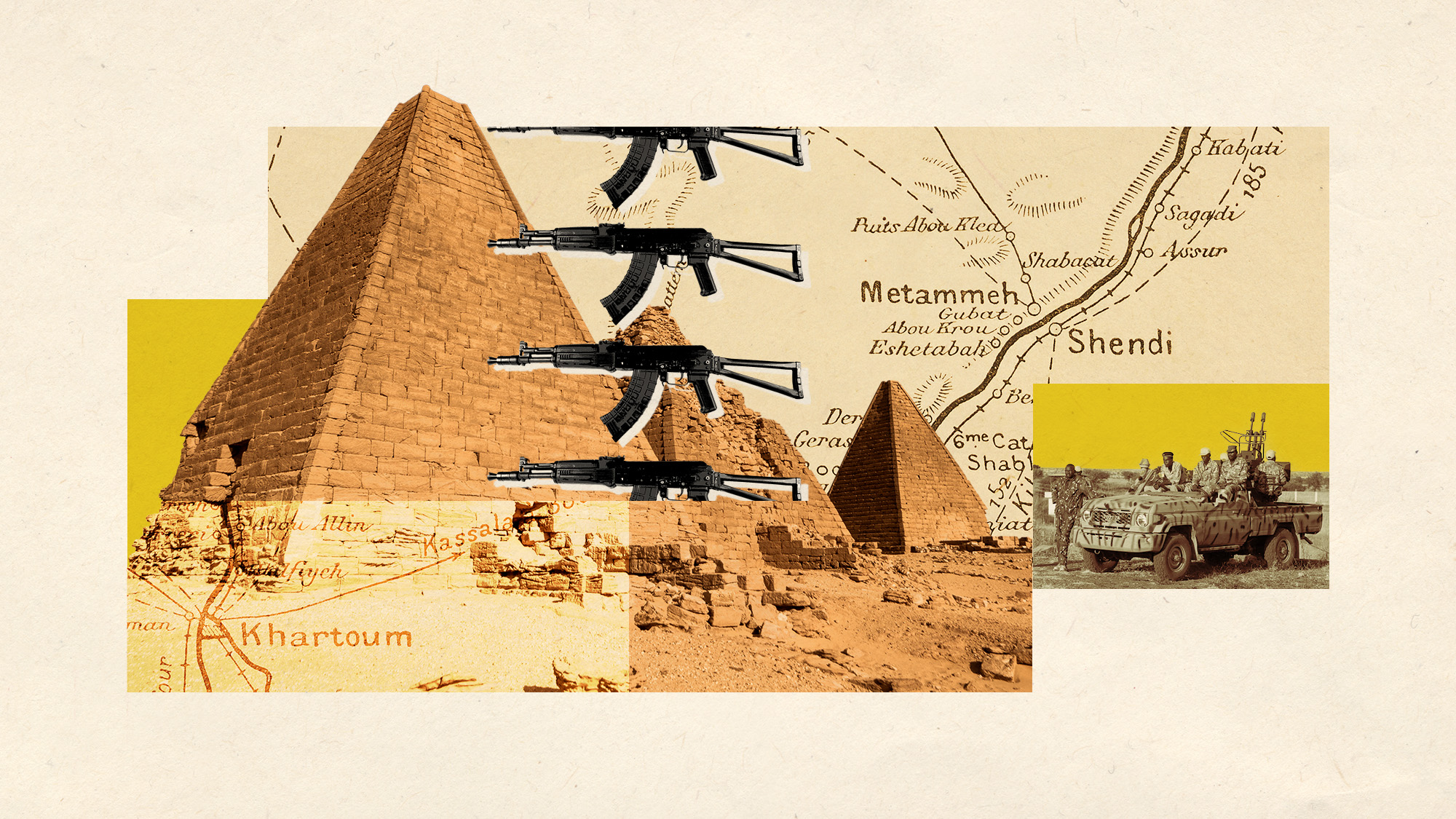

Sudan's forgotten pyramids

Sudan's forgotten pyramidsUnder the Radar Brutal civil war and widespread looting threatens African nation's ancient heritage

-

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raid

Harriet Tubman made a general 161 years after raidSpeed Read She was the first woman to oversee an American military action during a time of war

-

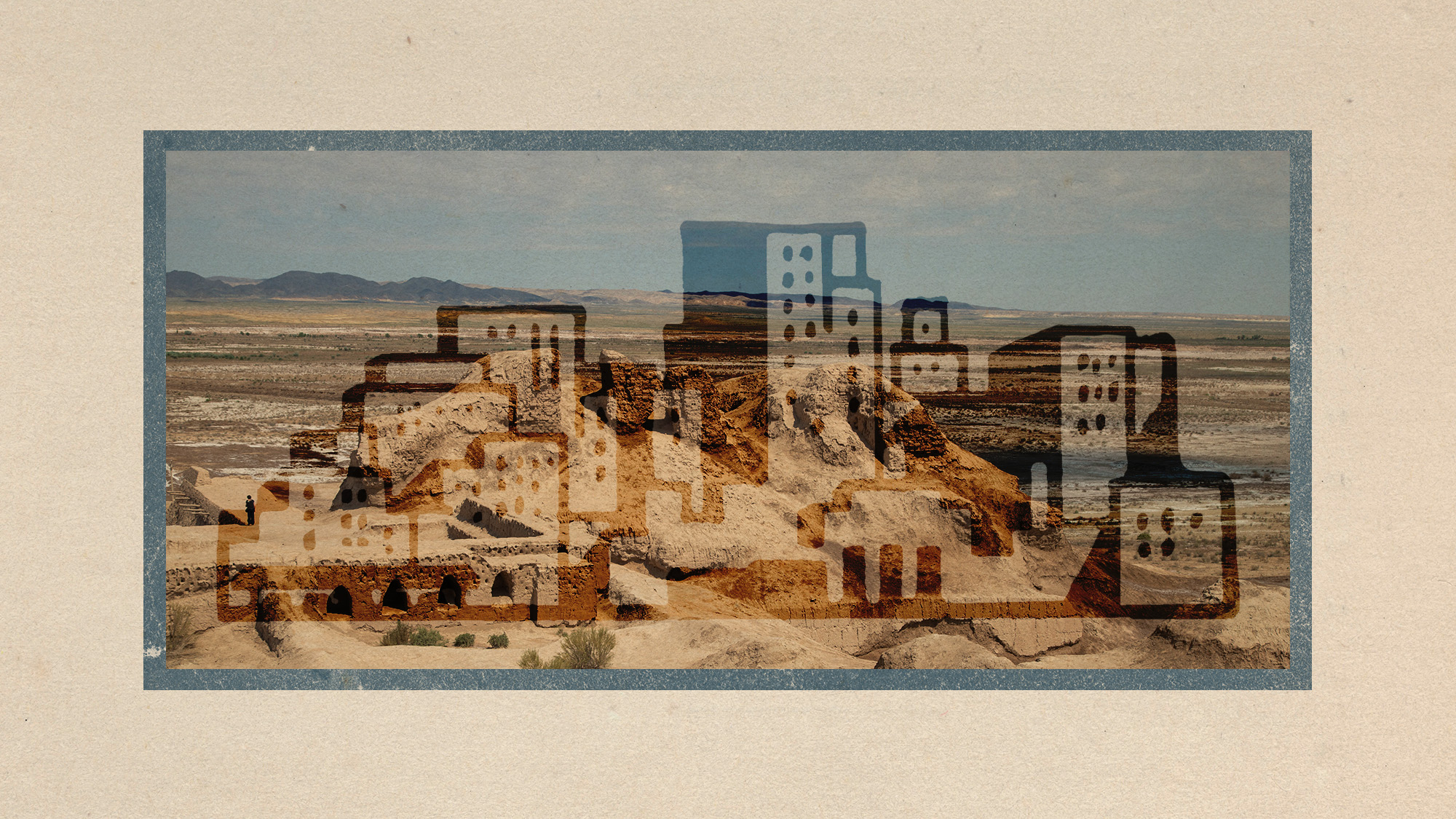

Two ancient cities have been discovered along the Silk Road

Two ancient cities have been discovered along the Silk RoadUnder the radar The discovery changed what was known about the old trade route

-

Stonehenge: a transformative discovery

Stonehenge: a transformative discoveryTalking Point Neolithic people travelled much further afield than previously thought to choose the famous landmark's central altar stone

-

Haredim: Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jews now facing conscription

Haredim: Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jews now facing conscriptionThe Explainer Religious community pays few taxes, receives vast subsidies and has avoided military service, provoking ire of wider society

-

Namibia grapples with legacy of genocide on Shark Island

Namibia grapples with legacy of genocide on Shark IslandUnder the radar A non-profit research agency believes it has located sites of unmarked graves of prisoners