The real story behind the Stanford Prison Experiment

'Everything you think you know is wrong' about Philip Zimbardo's infamous prison simulation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Stanford Prison Experiment of 1971 is one of the most famous – and infamous – psychological experiments conducted, still discussed in classrooms and pop culture more than half a century on. But "everything you think you know about this study is wrong", filmmaker Juliette Eisner told Ars Technica.

Eisner is the director of National Geographic's recent three-part series "The Stanford Prison Experiment: Unlocking the Truth", which features many of the study's participants speaking out for the first time. She "debunks" the experiment and investigates why it has "captured imaginations" for so long, despite being "riddled" with "lies" and "manipulation".

What was the Stanford Prison Experiment?

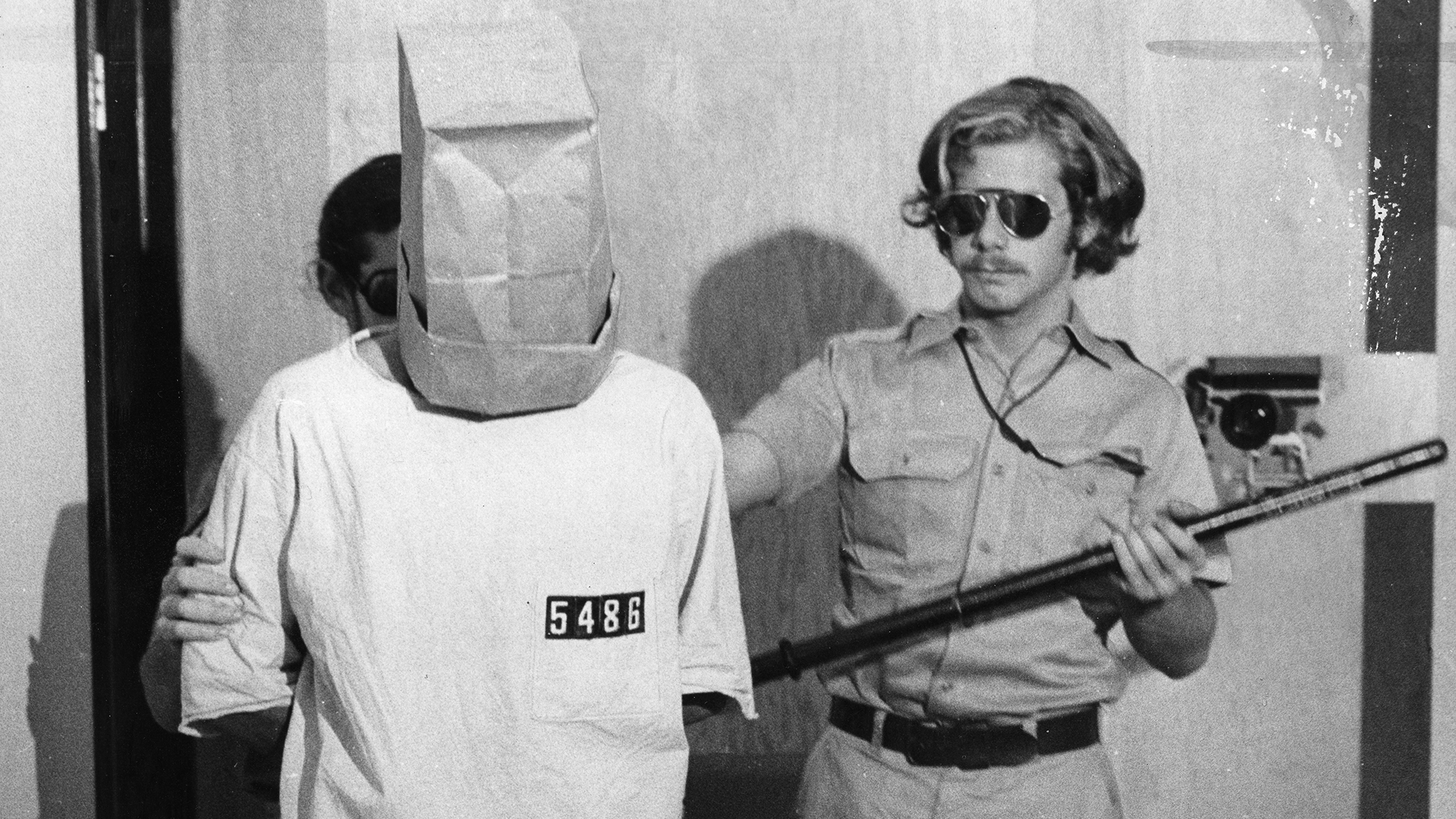

In August 1971, a group of students were "arrested" and hauled to "Stanford County Prison", which was, in reality, the basement of the psychology building of Stanford University, in California. The men had responded to an ad from Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo seeking volunteers for "a psychological study of prison life", said The New Yorker.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Twenty-four participants – all middle class, male college students – had been chosen for the study. A coin flip decided which of them would be prison guards and which would be prisoners. Rooms in the basement were turned into makeshift cells, with a janitor's cupboard acting as "the hole" for solitary confinement.

Although the men were willing participants, they had not been warned about the mock arrests or of the exact nature of the treatment they would face. The breaches in ethics had already begun, said Ars Technica, and they would not stop for six days, when Zimbardo called off the two-week study early.

What was Zimbardo trying to prove?

Zimbardo saw his study as a follow up to 1961's Milgram experiment, in which participants administered what they believed were powerful electric shocks to victims (played by actors) at the instruction of an authority figure. "Whereas Milgram’s research was all about the power of individual authority over an individual person, the Stanford Prison Experiment was all about the ability for a system to repeatedly create situations that strongly influence behaviour," Zimbardo said in a 2009 interview.

Based on his observations of interactions between the guards and inmates, Zimbardo concluded that holding a position of power could quickly "make normal people act like tyrants", said Time. An advocate for prison reform, the psychologist hoped to demonstrate that the prison environment encouraged this dehumanisation and brutality.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What happened during the experiment?

"Things became dark almost immediately," said Time. Guards, "drunk on power", tormented prisoners, denying then sleep, forcing some to strip naked, defecate in buckets and simulate sodomy, all while bombarding them with verbal abuse. Several prisoners left the experiment early, some reporting extreme emotional distress.

On day five, Zimbardo's then-girlfriend, Christina Maslach, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, visited the "prison". She was "so appalled" with the "lack of oversight" and "immoral" nature of the study, she convinced Zimbardo to end the experiment the next day.

Why was the experiment so controversial?

The study has long been criticised for a lack of ethical guidelines and, according to Ars Technica, is credited as the reason US universities had to "overhaul" their requirements for experiments involving human subjects.

French researcher Thibault Le Texier has been a major force behind debunking the experiment's methodology and conclusions. He argues Zimbardo's conclusions were "written out an advance" and the study was "carefully manipulated", a critique "largely confirmed" by National Geographic's series, said Ars Technica. For instance, the guards received "extensive instruction" on how to best dehumanise the prisoners, said Time.

Stanford prison's pop culture "cachet" relies on the misconception that the volunteers transformed into "submissive prisoners and tyrannical guards", said The New Yorker. However, only about a third of the guards displayed abusive behaviour and even that is far from indicative: several said their behaviour was play-acting, a conscious attempt to fulfil the role they believed they had been assigned.

The idea that the participants were putting on an act to satisfy the experiment organisers suggests "the opposite of Zimbardo's conclusions", journalist Jon Ronson wrote on X, "that evil lies within us".

Did the study have any value?

In 2002, psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher restaged the prison experiment in the BBC's "The Experiment". The set-up was closely modelled on Zimbardo's study, although the guards were not coached on how to behave towards the inmates. In the BBC study, the guards did not abuse their authority and prisoners ended up defying their captors and staging a revolt.

This very different outcome "sharpens and clarifies" the meaning of the Stanford Prison Experiment, said The New Yorker. The conclusion is not that "any random human being is capable of descending into sadism", but "that our behaviour largely conforms to our preconceived expectations". If "certain institutions and environments demand those behaviours" perhaps they "can change them", too.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Haredim: Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jews now facing conscription

Haredim: Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jews now facing conscriptionThe Explainer Religious community pays few taxes, receives vast subsidies and has avoided military service, provoking ire of wider society

-

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensions

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensionsThe Explainer Eighty years ago, the Allies carried out the D-Day landings – a crucial turning point in the Second World War

-

Namibia grapples with legacy of genocide on Shark Island

Namibia grapples with legacy of genocide on Shark IslandUnder the radar A non-profit research agency believes it has located sites of unmarked graves of prisoners

-

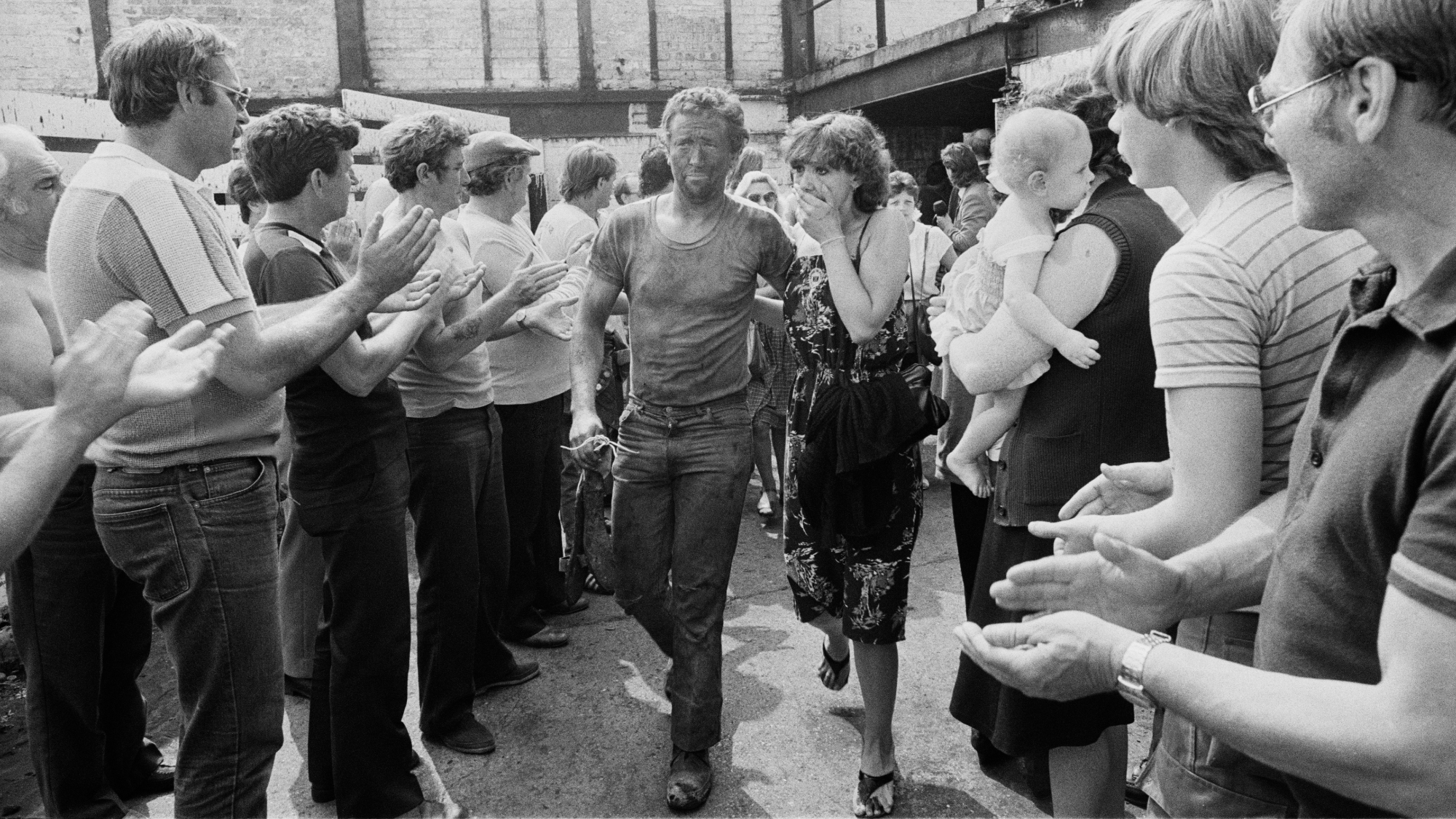

Why the miners' strike was so important

Why the miners' strike was so importantThe Explainer It is 40 years since most of Britain's coalminers went on strike, in the most bitter and divisive industrial dispute in recent history

-

D-Day: why the Normandy invasion was so important

D-Day: why the Normandy invasion was so importantThe Explainer Two days of events are being held to remember historic beach landings 80 years on