D-Day: why the Normandy invasion was so important

Two days of events are being held to remember historic beach landings 80 years on

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Special commemorations are being held on both sides of the English Channel to mark the 80th anniversary of D-Day. Veterans and their families, politicians and dignitaries, with King Charles among them, have been attending events in Portsmouth and Normandy to remember one of the most significant military operations in history and honour those who died.

Very few Allied soldiers who took part in the Second World War landings are still alive, and those who remain are now close to or more than 100 years old. Many of those who survive have travelled to the South Coast and northern France to remember "those who paid the ultimate price" and to carry "a message for generations behind them, who owe them so much: Don't forget what we did," said Politico.

D-Day, or Operation Neptune, was the largest amphibious invasion in military history. More than 150,000 troops landed by sea and air along a 50-mile stretch of the Normandy coast on 6 June 1944 and, despite more than 4,000 Allied losses, it was the first step of the ultimately successful Operation Overlord, the campaign to liberate northwest Europe from occupation by Nazi Germany.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Within a year of the landings, Adolf Hitler was dead and Germany had surrendered to the Allied forces, ending the Western theatre of the war.

What happened on D-Day?

In the early hours of 6 June 1944, Operation Neptune began. Taking the thinly stretched Nazi defences by surprise, some 156,000 Allied troops sailed across the Channel from ports on the south coast of England and stormed the beaches of Normandy at five separate points, codenamed Utah, Juno, Sword, Omaha and Gold.

A total of 7,000 ships were involved in the operation, including 3,500 troop carriers, 290 escort vessels and 250 minesweepers.

The Nazi defences "suffered from the complex and often confused command structure of the German army, as well as the constant interference of Adolf Hitler in military matters", said the Imperial War Museum (IWM). German command still considered the "initial attacks" of the Normandy landings – including paratroopers dropped deeper into Normandy some five hours before the beach landings – a "diversionary tactic" and chose not to deploy further units in a counter-offensive, said the BBC.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But "not all the landings were successful" immediately, said CNN. Unanticipated factors like "strong currents" forced American vessels at Omaha beach away from their targeted landing points, "delaying and hampering the invasion strategy".

The British and Canadian forces overcame "light opposition" to secure footholds at Sword and Gold beaches, as did the Canadians at Juno, said History.com. The American units at Utah beach likewise faced modest resistance. However, the US suffered significant casualties at Omaha where they lost more than 2,000 personnel.

The Allies are estimated to have suffered at least 10,000 casualties that day, with more than 4,000 confirmed dead, but by the evening, five vital access points for Allied military operations into Europe had been established. By 11 June, "326,000 troops, more than 50,000 vehicles and some 100,000 tons of equipment had landed at Normandy", said History.

Why was the invasion so significant?

Prior to D-Day, the Allied forces' access to Western Europe had been limited by the fall of France to the Nazis in 1940. By June 1944, an operation was under way to liberate the Italian peninsula, but establishing a foothold in Normandy was essential for a full-scale invasion.

Following their defeat on the beaches, the Nazi forces in Western Europe were so depleted that the Allies were able to advance, capturing Paris by 25 August, and Brussels by 3 September. Meanwhile, German resources were tied up on the Eastern Front in the Soviet Union.

Hitler's defensive strategy was enormously detrimental to the Nazi war effort. He refused to allow his commanders freedom to give up ground, inadvertently handing the Allies "a more complete victory than they could have hoped for, as enemy units were sucked into the maelstrom and destroyed" across France, said IWM historian Ian Carter.

By late April 1945, the Allies had advanced deep into German territory and liberated Munich, one of the key Nazi strongholds. Unable to defend two fronts at once, the Nazis were decisively beaten by the Red Army in Berlin, leading to the suicide of Hitler and forcing the surrender of Nazi Germany on 8 May 1945.

"Without D-Day," said Frank Blazich, curator of military history at the Smithsonian Institute's National Museum of American History, "the total defeat of Nazi Germany and return of democracy to Western Europe could not be envisioned as inevitable."

How is it being commemorated?

Two days of events are being held to remember D-Day on its 80th anniversary. A "spectacular cultural commemoration" took place in Southsea, Portsmouth – from where many vessels were launched on D-Day – on Wednesday, with King Charles and Rishi Sunak among those in attendance to honour surviving veterans and those who fell, said The Guardian.

An "international event" will take place today on Omaha beach and will be attended by US President Joe Biden and Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. It has been a rare trip for King Charles, who has "made only a few public appearances since his cancer diagnosis", but he will also join the events in France today.

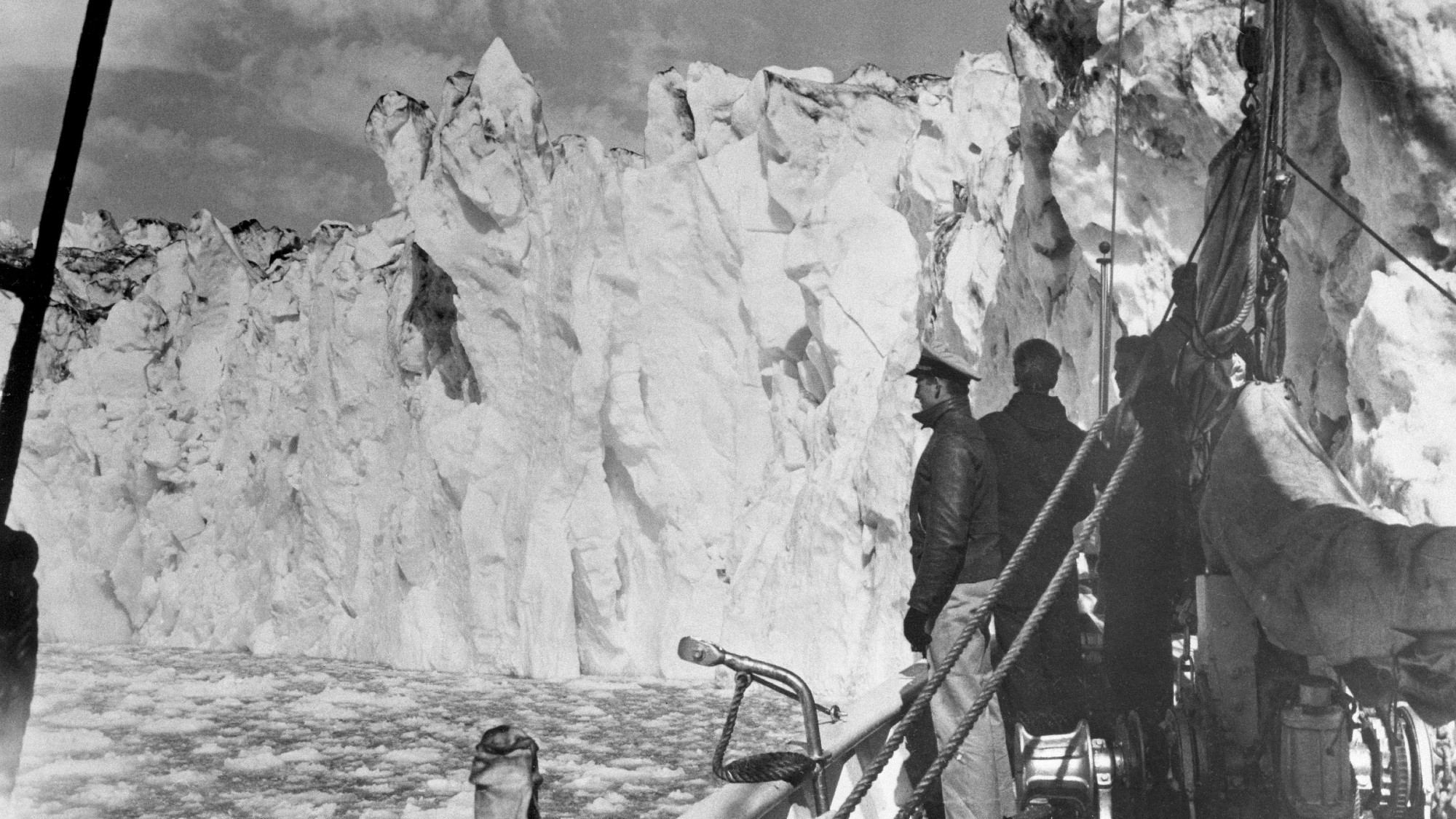

Overnight, the frigate HMS St Albans replicated the journey Allied troops would have made 80 years ago. Many veterans made their way to Normandy earlier this week to begin commemorations. As they set sail, said Politico, they gathered "on deck and waved like rockstars to well-wishers who cheered them off".

Richard Windsor is a freelance writer for The Week Digital. He began his journalism career writing about politics and sport while studying at the University of Southampton. He then worked across various football publications before specialising in cycling for almost nine years, covering major races including the Tour de France and interviewing some of the sport’s top riders. He led Cycling Weekly’s digital platforms as editor for seven of those years, helping to transform the publication into the UK’s largest cycling website. He now works as a freelance writer, editor and consultant.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World War

Why Greenland has been a US military stronghold since the Second World WarIn Depth American interest in acquiring Greenland is rooted in decades of military and economic strategy

-

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victory

How China rewrote the history of its WWII victoryIn Depth Though the nationalist government led China to victory in 1945, this is largely overlooked in modern Chinese commemorations

-

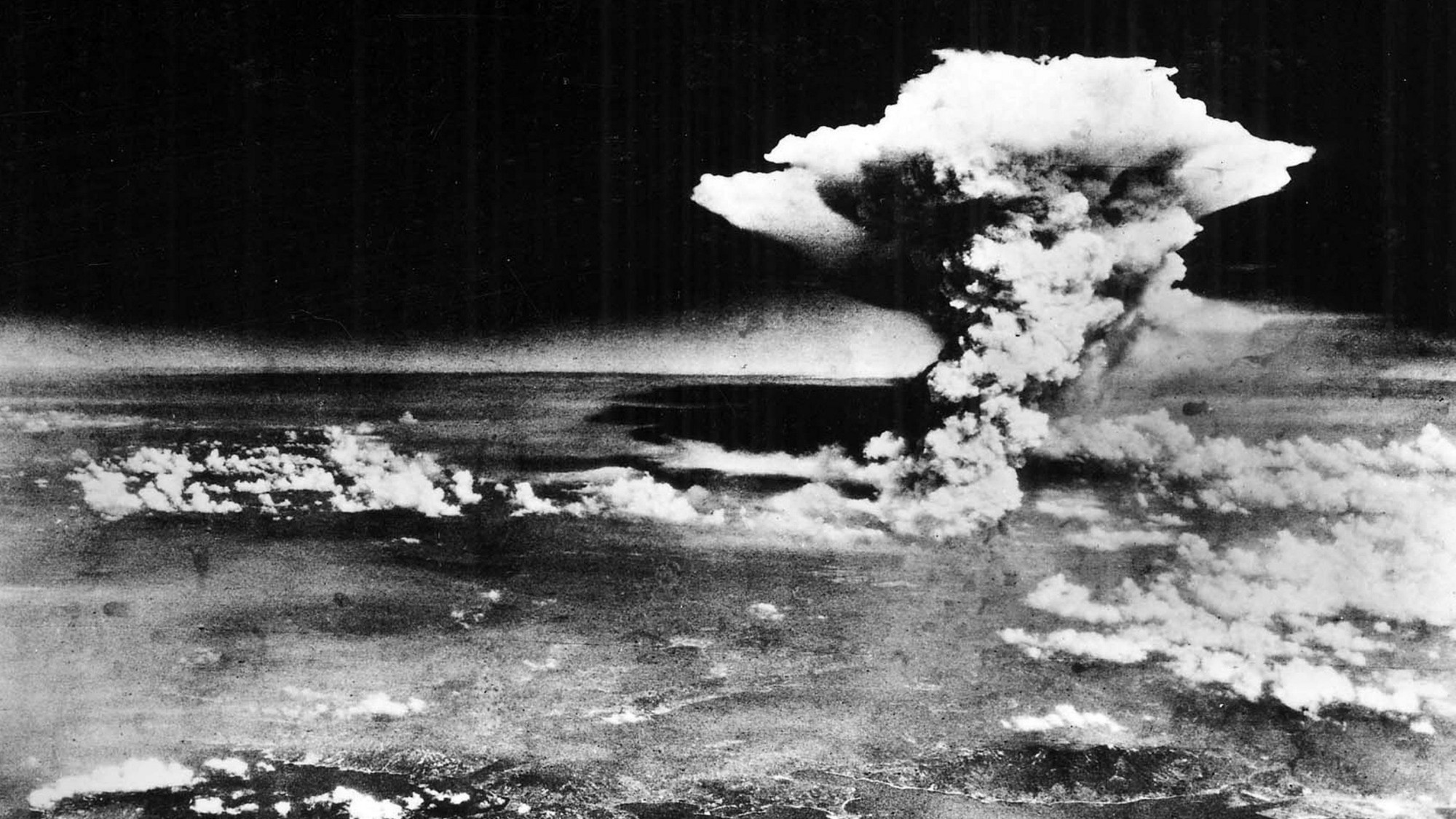

America's controversial path to the atomic bomb

America's controversial path to the atomic bombIn Depth The bombing of Hiroshima followed years of escalation by the U.S., but was it necessary?

-

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for Nazis

Argentina lifts veil on its past as a refuge for NazisUnder the Radar President Javier Milei publishes documents detailing country's role as post-WW2 'haven' for Nazis, including Josef Mengele and Adolf Eichmann

-

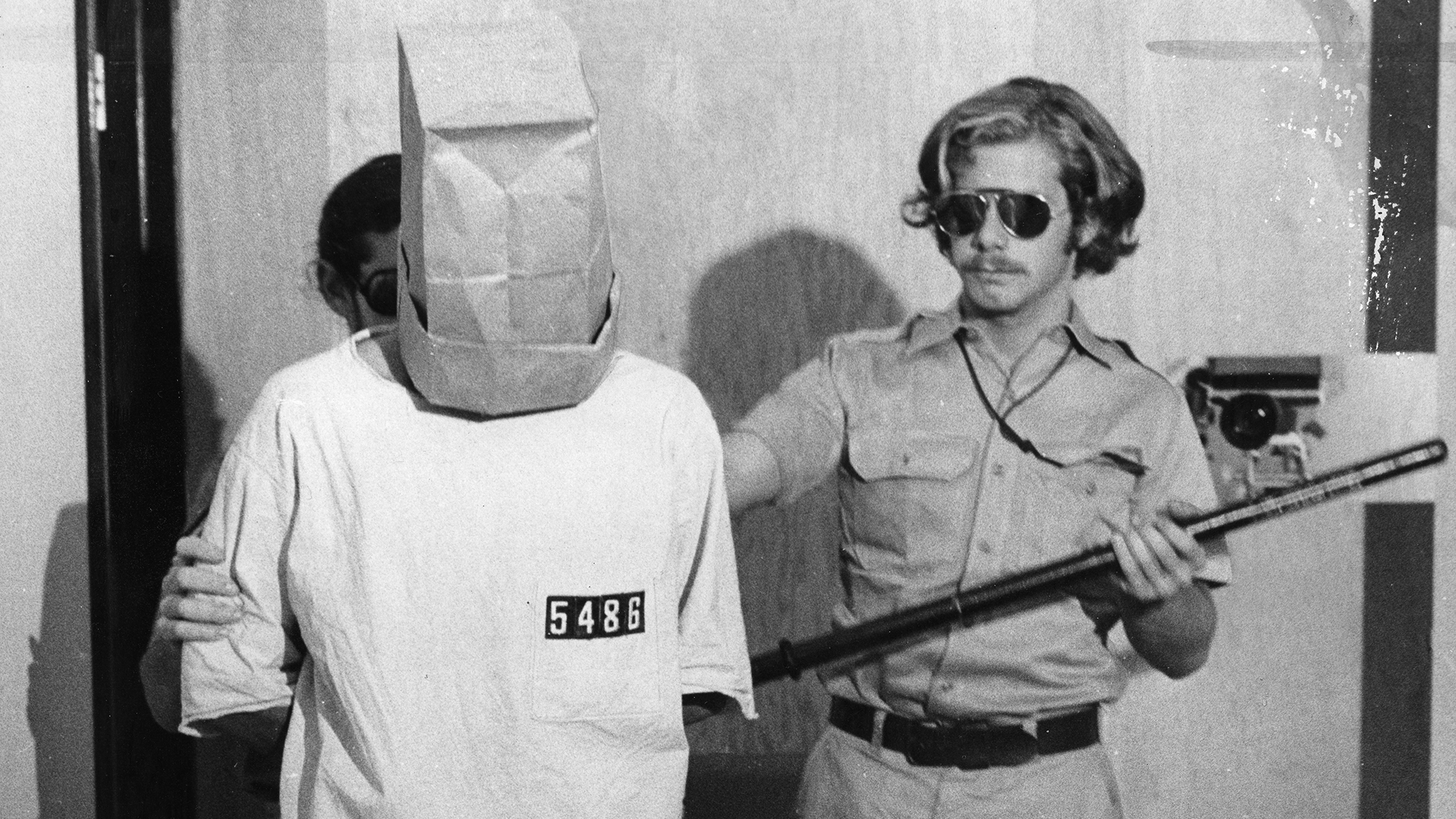

The real story behind the Stanford Prison Experiment

The real story behind the Stanford Prison ExperimentThe Explainer 'Everything you think you know is wrong' about Philip Zimbardo's infamous prison simulation

-

Haredim: Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jews now facing conscription

Haredim: Israel's ultra-Orthodox Jews now facing conscriptionThe Explainer Religious community pays few taxes, receives vast subsidies and has avoided military service, provoking ire of wider society

-

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensions

D-Day: how allies prepared military build-up of astonishing dimensionsThe Explainer Eighty years ago, the Allies carried out the D-Day landings – a crucial turning point in the Second World War

-

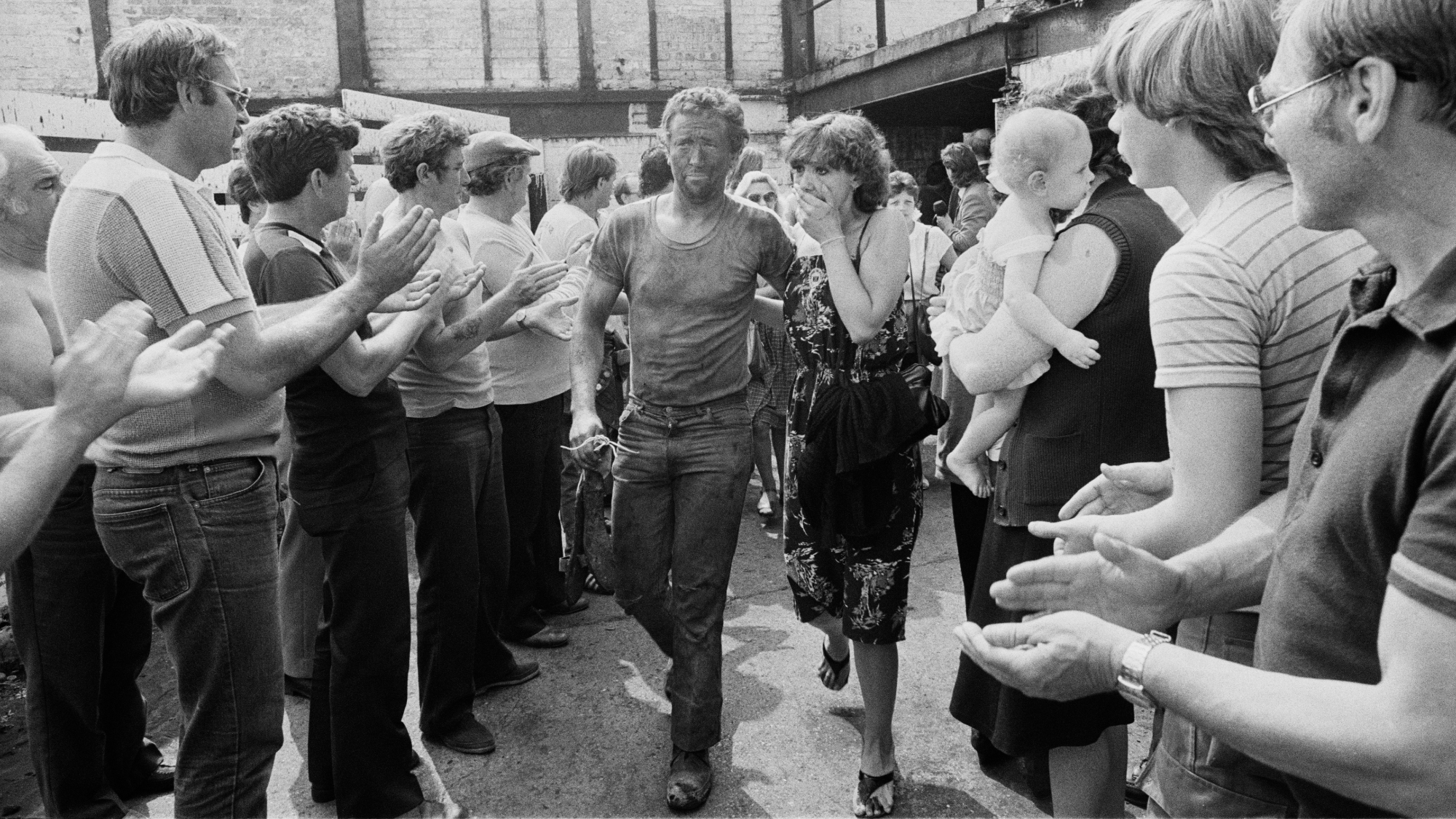

Why the miners' strike was so important

Why the miners' strike was so importantThe Explainer It is 40 years since most of Britain's coalminers went on strike, in the most bitter and divisive industrial dispute in recent history