Why the miners' strike was so important

It is 40 years since most of Britain's coalminers went on strike, in the most bitter and divisive industrial dispute in recent history

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How did the strike begin?

The immediate cause was the announcement in March 1984 by the National Coal Board (NCB) that 20 pits would be closing, at the cost of 20,000 jobs. After coming to power in 1979, Margaret Thatcher had made it clear that she wanted to close down unprofitable collieries, importing cheaper coal from abroad; the NCB wanted the nationalised industry to break even by 1988. However, Arthur Scargill, president of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), argued that no pit should be shut if it had coal reserves and claimed (correctly, it later transpired) that there was a "secret hit-list" of more than 70 pits marked for closure. On 6 March, miners at Cortonwood Colliery in South Yorkshire, having learnt that their pit was slated for closure, walked out. The strikes soon spread across Yorkshire and beyond. On 12 March, the NUM declared a nationwide strike.

Why was it so important?

It was the most divisive, and consequential, industrial dispute in postwar British history. Between 6 March 1984 and 3 March 1985, some 140,000 out of Britain's 187,000 working coal miners walked out. Although the coal industry was in rapid decline in the early 1980s, the NUM was still the UK's most powerful union, and had secured significant victories by striking in 1972 and 1974, crippling the Tory government. Coal accounted for almost 80% of the UK's electricity supply; miners kept the lights on. A bitter war of attrition played out over those 12 months, pitting the NUM not just against the government but – very damagingly for the union – against miners who wanted to keep working.

Why was this so damaging for the NUM?

Scargill refused to hold a national ballot of members on whether to strike: he had lost three ballots on strike action since becoming NUM president in 1982, and feared losing again. He argued that miners whose jobs were apparently safe should not be allowed to vote against a strike designed to protect jobs in vulnerable pits. So instead, ballots were held in individual regions. Some, particularly in Nottinghamshire (the most productive area), never voted to strike; miners there complained that the charismatic, militant Scargill had ulterior political motives (by his own admission, he wanted to bring down the government). The decision proved costly, since a national ballot was required by law. Without it, the Labour Party and much of the media did not support the strike – and the miners were badly divided.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What effect did this have?

Within a fortnight, only 11 of the 170 or so pits left in Britain were working normally. Over the following year, the strike was especially "solid" in Yorkshire, Scotland, Kent and south Wales; and weakest in the Midlands, and particularly Nottinghamshire. Many hardline miners joined "flying pickets": men who travelled in their thousands – often from Yorkshire – to shore up support at other collieries (this was illegal, under a law passed in the 1970s). In Nottinghamshire, pitched battles between striking miners and "scabs" determined to work became a regular fixture over spring and summer. Before long, ministers had realised that their initial calculation that the strike would be over in a few months was mistaken. Scargill and the NUM would not easily cave in; but the government, too, was determined and well-prepared.

How had the government prepared?

In 1977, before even winning power, the Tory MP Nicholas Ridley had drawn up a plan to defeat the NUM by stockpiling coal for power stations, and building up a powerful police presence: officers were mobilised from forces across the country. In Nottinghamshire, they frequently intercepted flying pickets on main roads into the county, turning back cars full of men. Those that did make it to the picket lines were confronted by officers, many of whom were kitted out in riot gear, or on horseback. The miners fought running battles with officers; hundreds of people were injured daily. About 11,000 miners were arrested – mostly for public order offences – and 8,000 were prosecuted. The most infamous of these conflicts took place at Orgreave coking plant on 18 June 1984. Thatcher secretly prepared to declare a state of emergency and call in the Army to deal with them, according to government papers released in 2014. She told her MPs that she regarded striking miners as "the enemy within".

How did the dispute end?

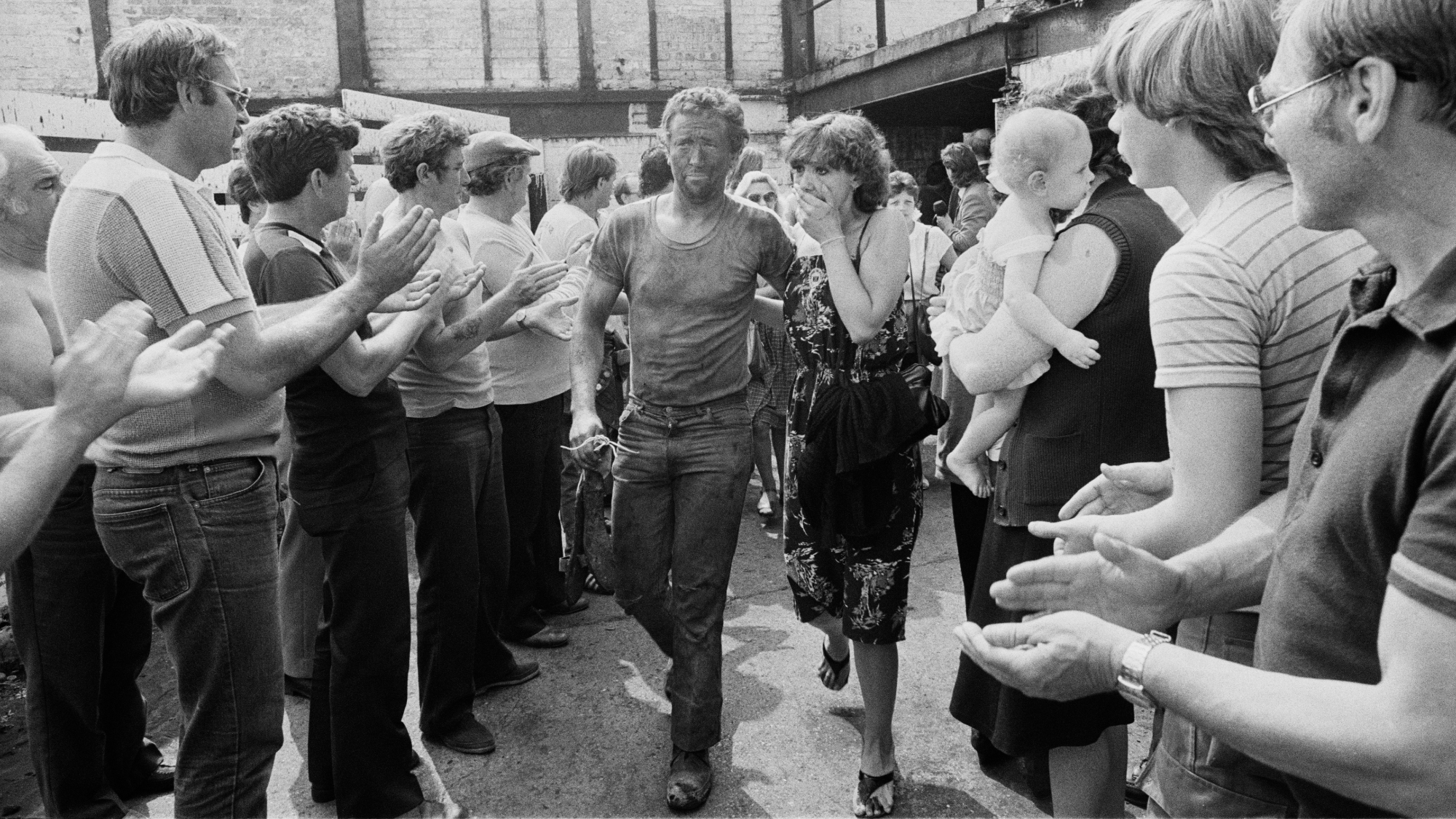

With a crushing defeat for the NUM. Actually, it came close to victory in the autumn, when NACODS, the union for overseers and safety officials, voted to strike; this would have closed the pits. But the NCB won them round, and the miners' last chance of victory slipped away. They endured great poverty, after months without pay. Despite an impressive effort by the miners and their supporters to create what one official called "an alternative welfare state" – soup kitchens, food parcels – union funds were running low by Christmas, and miners and their families were desperate; ministers moved to block benefits for their dependents. On 3 March 1985, the NUM held a conference at which delegates narrowly voted to end the strike; and the miners marched back to work.

What is the strike's legacy?

It is still bitterly contested. On the Right, Thatcher's determination to face down the miners was seen as a triumph against over-mighty, undemocratic union power; it paved the way for the liberalisation and globalisation of the British economy. It also, however, heralded the destruction of the British coal industry. The NCB pushed ahead with pit closures. By 1994, when the industry was privatised, only 15 pits remained open. The last deep coal mine, Kellingley, closed in 2015. The socioeconomic effects on miners and their families were devastating. Unemployment soared; tight-knit communities were ripped apart. To this day, many still have an acute sense of being "left behind".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

American empire: a history of US imperial expansion

American empire: a history of US imperial expansionDonald Trump’s 21st century take on the Monroe Doctrine harks back to an earlier era of US interference in Latin America

-

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa Parks

Claudette Colvin: teenage activist who paved the way for Rosa ParksIn The Spotlight Inspired by the example of 19th century abolitionists, 15-year-old Colvin refused to give up her seat on an Alabama bus

-

Decking the halls

Decking the hallsFeature Americans’ love of holiday decorations has turned Christmas from a humble affair to a sparkly spectacle.

-

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?

Hitler: what can we learn from his DNA?Talking Point Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator is the latest documentary to posthumously diagnose the dictator

-

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025

The seven strangest historical discoveries made in 2025The Explainer From prehistoric sunscreen to a brain that turned to glass, we've learned some surprising new facts about human history

-

How did Kashmir end up largely under Indian control?

How did Kashmir end up largely under Indian control?The Explainer The bloody and intractable issue of Kashmir has flared up once again

-

The fall of Saigon

The fall of SaigonThe Explainer Fifty years ago the US made its final, humiliating exit from Vietnam

-

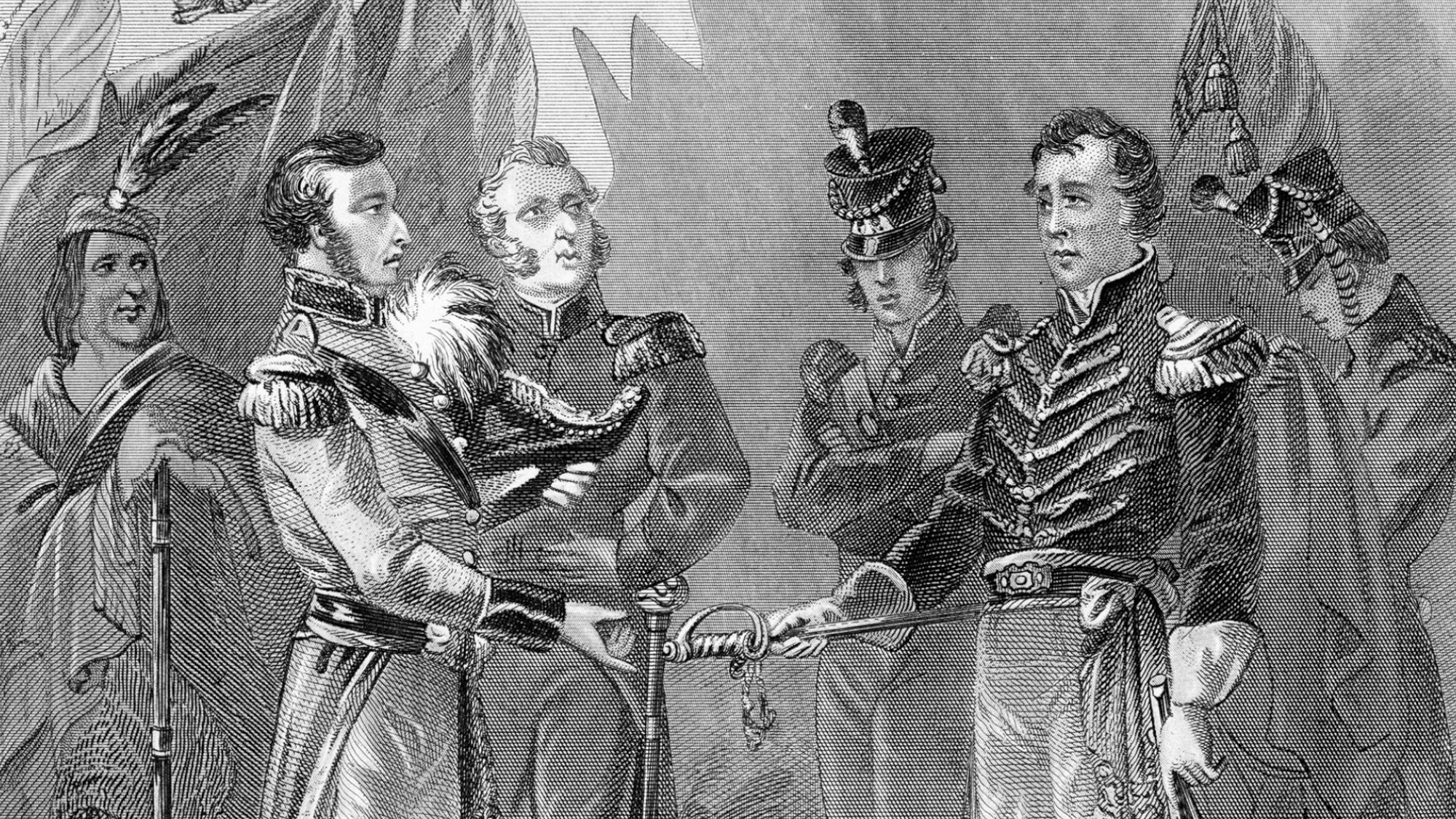

When the U.S. invaded Canada

When the U.S. invaded CanadaFeature President Trump has talked of annexing our northern neighbor. We tried to do just that in the War of 1812.