A whole new world: redrawing the Mercator map

African Union joins calls to ditch 'colonial distortion' and portray countries at more accurate size

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"On classroom walls from Lagos to London", the standard map of the world depicts an "inflated Britain at the centre" and a dramatically "shrunken Africa", said The Times.

But this could soon change. The African Union has thrown its weight behind a "Correct the Map" campaign, calling for an end to the use of the standard Mercator map in favour of one that accurately reflects the scale of the world's second-largest continent.

"It might seem to be just a map," said Selma Haddadi, of the African Union Commission, "but in reality it is not."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

'World's longest misinformation campaign'

Created in 1569 by Flemish geographer Gerardus Mercator, the world map commonly used today "did a good job" of depicting the general shape of countries, said USA Today.

However, when trying to map a spherical planet on to a flat piece of paper, "something's got to give". In the case of the Mercator map and its successors, "what gives is the size of places near the poles", which become distended compared to land masses nearer the Equator.

The result? A map that "disproportionately" enlarges the "rich and powerful regions of the world", said Al Jazeera. In the Mercator projection, Europe appears to be bigger than South America, when it's "actually half its size", while Greenland is "shown to be relatively the same size as Africa" when it could fit inside the continent "14 times over".

"It's the world's longest misinformation and disinformation campaign," Moky Makura, executive director of Africa No Filter, told Sky News. "It just simply has to stop."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Haddadi, from the African Union Commission, said the Mercator map creates a "false impression" of Africa as "marginal", despite its size. These "stereotypes" then trickle down into "media, education and policy".

Advocacy group Speak Up Africa argues that Mercator impacts "Africans' identity and pride", especially children who "encounter it early in school".

'Colonial distortion'

Calls for alternative maps have formed part of wider efforts to challenge Western-centred representations in education for decades. After years of "colonial distortion", hundreds of schools in Boston received a "very different" map that sought to actively "correct the Western world's distorted view of its own size", said The Independent in 2017.

Several African nations have begun replacing Mercator maps in schools with alternatives. The current campaign is "actively working" on promoting a curriculum across the continent that uses the so-called Equal Earth map projection, which "tries to reflect countries' true sizes", said Reuters.

The Mercator projection is still "widely used" in "schools and tech companies" alike, but there has been progress towards adopting a more accurate map. The World Bank says it is "phasing out" the Mercator map, while the desktop version of Google Maps switched "to a 3D globe view in 2018, though users can still switch back to the Mercator if they prefer" and it remains the default view on the mobile app.

Rebekah Evans joined The Week as newsletter editor in 2023 and has written on subjects ranging from Ukraine and Afghanistan to fast fashion and "brotox". She started her career at Reach plc, where she cut her teeth on news, before pivoting into personal finance at the height of the pandemic and cost-of-living crisis. Social affairs is another of her passions, and she has interviewed people from across the world and from all walks of life. Rebekah completed an NCTJ with the Press Association and has written for publications including The Guardian, The Week magazine, the Press Association and local newspapers.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

Why recognizing Somaliland is so risky for Israel

Why recognizing Somaliland is so risky for IsraelTHE EXPLAINER By wading into one of North Africa’s most fraught political schisms, the Netanyahu government risks further international isolation

-

Benin thwarts coup attempt

Benin thwarts coup attemptSpeed Read President Patrice Talon condemned an attempted coup that was foiled by the West African country’s army

-

West Africa’s ‘coup cascade’

West Africa’s ‘coup cascade’The Explainer Guinea-Bissau takeover is the latest in the Sahel region, which has quietly become global epicentre of terrorism

-

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threat

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threatSpeed Read Trump has claimed the country is persecuting Christians

-

Sudan stands on the brink of another national schism

Sudan stands on the brink of another national schismThe Explainer With tens of thousands dead and millions displaced, one of Africa’s most severe outbreaks of sectarian violence is poised to take a dramatic turn for the worse

-

Protesters fight to topple one of Africa’s longstanding authoritarian nations

Protesters fight to topple one of Africa’s longstanding authoritarian nationsIn the Spotlight Cameroon’s president has been in office since 1982

-

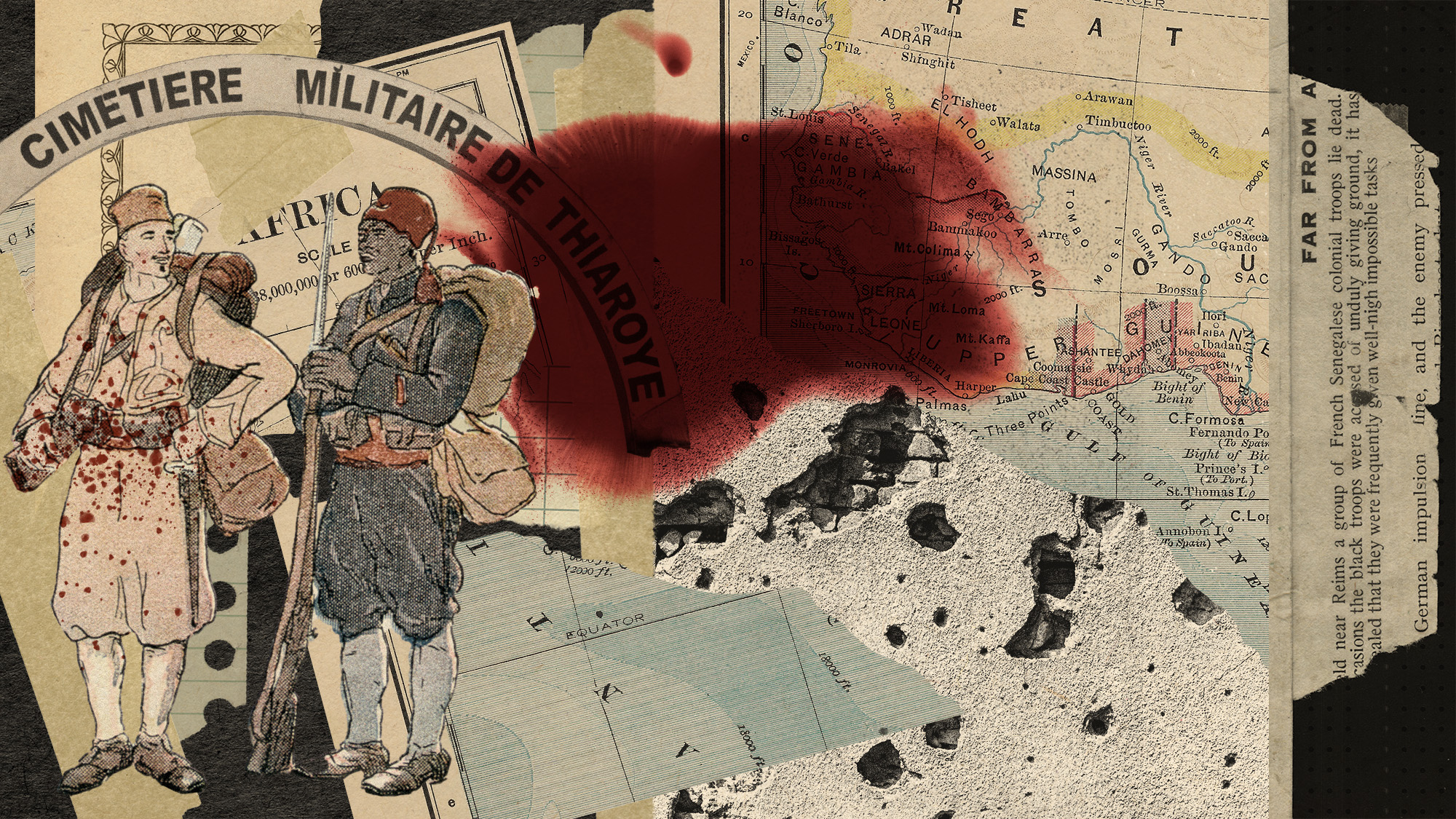

The WW2 massacre dividing Senegal and France

The WW2 massacre dividing Senegal and FranceUnder the Radar A new investigation found the 1944 Thiaroye attack on ‘unarmed’ African soldiers was ‘premeditated’, and far deadlier than previously recorded

-

The disputed claims about Christian genocide in Nigeria

The disputed claims about Christian genocide in NigeriaThe Explainer West African nation has denied claims from US senator and broadcaster