The most hunted man in Iraq

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi is wanted for a series of gruesome, high-profile atrocities in Iraq. How did this former petty criminal from Jordan become the symbol of a murderous insurgency?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What do we know about al-Zarqawi?

Iraq’s most wanted terrorist is a surprisingly shadowy figure. No one knows where al-Zarqawi is, or exactly what he looks like. A recent Marine Corps analysis described him as having a “possible prosthetic leg,” a “possible shoulder injury,” and a “possible Jordanian accent.” What is certain, however, is that his terrorist group, Tawhid and Jihad, has carried out a series of bloody atrocities in postwar Iraq. In August 2003, the group bombed the United Nations’ Baghdad headquarters, killing 17; this March, it killed 180 in multiple suicide bombings of Shiite mosques in Baghdad and Karbala. But it is al-Zarqawi’s talent for media manipulation—and for gruesome executions—that has brought him international infamy.

Who has he executed?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Al-Zarqawi’s group has made a specialty of kidnapping foreign nationals and beheading them on videotape. In a now familiar tableau, the terrorists pronounce the death sentence on their blindfolded victim, then savagely saw off his head. On one tape, aired in May, a man identifying himself as al-Zarqawi personally decapitated U.S. businessman Nick Berg and held his severed head aloft. More recently, al-Zarqawi’s henchmen did the same to British engineer Kenneth Bigley, as he wept and pleaded for mercy. The U.S. has now offered a $25 million reward for information leading to al-Zarqawi’s capture or death.

Where did he come from?

Al-Zarqawi is a Jordanian, born Ahmed al-Khalayleh, in 1966. His poverty-stricken hometown of Zarqa, from which he took his name, was known as the “Chicago of the Middle East” for its lawlessness. Although his father was a local sheikh and committed Muslim, who had fought against the fledgling state of Israel, al-Zarqawi was a dissolute youth. In his teens he was a petty criminal and drug dealer, barely literate but quick with a knife. Gradually, though, he became interested in radical Islam. He gave up drugs, and in the late 1980s went to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. He returned to Jordan in 1992; a year later he was imprisoned for plotting to overthrow the monarchy of King Hussein.

How did prison affect him?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It turned him into a committed jihadist, determined to transform the world into a medieval Islamic caliphate. Renouncing modernity, al-Zarqawi committed the entire Koran to memory and used hydrochloric acid to burn off a homemade tattoo he had inscribed on his left forearm. He also recruited many fellow prisoners, over whom he seemed to have a mysterious hold. “He could direct his men simply by moving his eyes,” says his former prison doctor. At that time, however, his hatred was not directed at America. “His main foe was Russia and communism,” recalls an inmate. “Americans, at least, had faith in God.”

When did his terrorist activities begin in earnest?

After he was released from jail in 1999, al-Zarqawi made his way back to Afghanistan. There, under the protection of the Taliban, he set up a terrorist training camp near the city of Herat. He specialized in chemical weaponry, and appears to have had operatives in several countries. In April 2000, police in Jordan broke up what might have been an al-Zarqawi cell, which had been plotting to detonate 20 tons of chemicals in central Amman. (The blast, authorities estimated, could have killed 80,000.) When the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, in the fall of 2001, al-Zarqawi was a prime target. His leg was badly damaged in a bombing raid, and he fled to Iran. But by early 2002 he had surfaced in Iraq.

What was he doing there?

He was operating another terrorist camp, near Khurmal in the northeastern Kurdish region of Iraq. There, he trained followers in the production and use of ricin and cyanide. His presence in Iraq was used by the Bush administration as part of the justification for war. In February 2003, when Secretary of State Colin Powell presented the case against Saddam Hussein to the U.N., he identified al-Zarqawi as an “associate” of Osama bin Laden, and as proof of the “sinister nexus” between Iraq and al Qaida. Last month, however, a CIA report found that there was no conclusive evidence that Saddam had given al-Zarqawi safe haven. In fact, some intelligence officials believe that al-Zarqawi spent his time in Iraq working with Kurdish radicals who were trying to overthrow the dictator.

So does he have links to al Qaida?

That, too, is questionable. In February, U.S. troops discovered a computer disk bearing a long, eloquent letter supposedly written by al-Zarqawi to bin Laden, in which he implores the al Qaida leader to send operatives to fight a holy war in Iraq. But many think the letter is a fake, since the language is too sophisticated for a man with little education. Several weeks ago, however, al-Zarqawi used a Web site to swear allegiance to bin Laden and al Qaida—a sign, say some experts, that he is cornered and desperate. “He was more of an al Qaida competitor,” says one U.S. military officer, “and resisted allying with them because he didn’t want to be dominated by them.”

How important is he, then?

Though the administration has depicted al-Zarqawi as the primary architect of Iraq’s postwar carnage, he may be responsible for only a small portion of the resistance. Iraqi guerrillas have told Western journalists that al-Zarqawi commands no more than 500 fighters, and that most Iraqi insurgents are disgusted by his beheadings and his bombing of civilians. Some skeptics think the U.S. has deliberately inflated al-Zarqawi’s importance to downplay the widespread scope of the insurgency. “The guy is on the run,” said one European intelligence official. “It would be almost impossible for him to calmly plan and execute the operations all over Iraq that some people believe he has done.”

How he got away

The Wall Street Journal,

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders

-

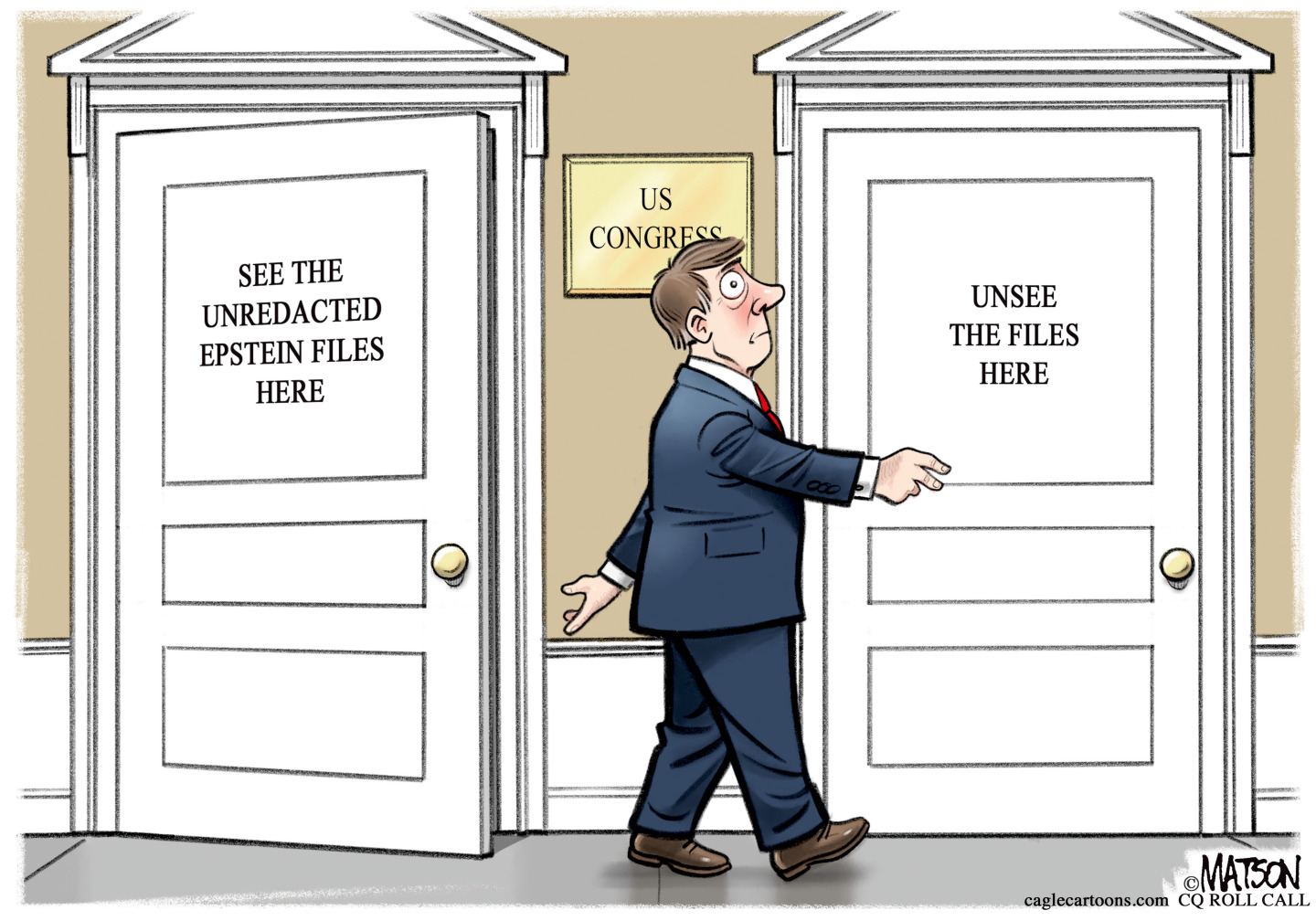

Political cartoons for February 11

Political cartoons for February 11Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include erasing Epstein, the national debt, and disease on demand