Musharraf: The indispensable ally

Pakistan’s ruling general, Pervez Musharraf, may be the U.S.’s most critical ally, but many in his country would like to see him dead. Can he survive?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Why is Pakistan so important?

It is the second-largest country in the Islamic world, and the only one with a nuclear arsenal—30 to 50 devices, according to Western intelligence estimates. It is also not a particularly stable country. Carved out of British India in 1947 to provide a homeland for the subcontinent’s Muslims, Pakistan has always been a shaky amalgam of rivalrous Muslim sects, with additional fault lines based on ethnicity and geography. No leader has ever been able to bind the people together for long in the name of Islam, writes author and Pakistan expert Mary Anne Weaver, “because in Pakistan, you must ask, ‘Whose Islam?’”

Are there many extremists?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yes. Many Pakistanis—a majority by some accounts—favor a fundamentalist form of Islam that has more in common with the former Taliban regime of Afghanistan than with modern varieties in places like Turkey and Indonesia. The country, largely Sunni, also still labors under a de facto caste system, with many privileges available only to the Brahmans, the highest and wealthiest caste. “And beneath the Brahmans is the army,” said Karachi businessman Adil Mufti. “It is our second caste.” Recruits in Pakistan’s 550,000-man army quickly learn the basic tenets of Pakistani nationalism: that Hindu India is bent on Muslim Pakistan’s destruction, that civilian politicians are corrupt, and that the army alone can assure the country’s survival. Gen. Pervez Musharraf is the latest in a string of army leaders who have ruled the 150 million Pakistanis.

What sort of man is he?

The well-educated son of a diplomat, Musharraf is a career military man with a distinct secular tilt. He’s known for having a taste for Johnnie Walker scotch and, in his single days, had a reputation as a ladies’ man. The world first became aware of him only five years ago, when, as army chief of staff, he directed a huge incursion of Pakistani forces into the Indian-held territory of Kargil, high in the Himalayas of Kashmir. In the news footage, Musharraf was seen leading his troops as a dashing commando in fatigues and a beret. The assault was the biggest Indo-Pakistan military clash in 28 years, gaining the alarming distinction as the first-ever direct combat involving two nuclear powers. Under pressure from the U.S., Pakistan’s prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, ordered a troop withdrawal. Four months later, after a bloodless coup, the humiliated civilian leader was gone and the swaggering Musharraf, now calling himself “Chief Executive,” was in charge.

Has he been a good leader?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

From the beginning, Musharraf, now 60, confounded the West, mixing saber rattling toward India with secular-sounding calls for a broad-based and even democratic government. U.S. officials had reason to hope that he would stand up to the Islamic fanatics. “Islam teaches tolerance, not hatred,” he said soon after taking power, “peace and not violence, progress and not bigotry.” But he cozied up to the Taliban fundamentalists who ran neighboring Afghanistan. President Bill Clinton, during a brief visit to Pakistan in March 2000, pointedly refused to be photographed shaking his hand. But Sept. 11 changed everything.

In what way?

After the terror attacks in New York and Washington, D.C., the U.S. demanded that Musharraf choose between the Taliban and the West. “You are either with us or against us,” President Bush reportedly told Musharraf. Almost overnight, Musharraf abandoned the Taliban. He allowed the U.S. to use Pakistani territory as a staging area in its war against Afghanistan, and he cracked down on homegrown militants. “Policies are made in accordance with environments,” Musharraf explained matter-of-factly. “The environment changed; our policy changed.” The policy change transformed Pakistan from an international pariah that had barged into the nuclear club to a key player in the U.S.’s global war on terrorism. But Musharraf still faces huge challenges from his own population, which is generally not happy with his rule.

What is their objection?

Many Pakistanis see Musharraf as far too friendly with the U.S., and too indifferent to their poverty. A civilian political opposition, most of whose leaders are in exile, would easily control a majority in an elected parliament. Islamic fundamentalists are trying to unseat Musharraf without an election—by assassinating him. In December, radicals detonated a huge bomb and blew up a bridge just a minute after Musharraf’s convoy crossed it. Eleven days later, two suicide bombers detonated explosives in pickup trucks as Musharraf’s motorcade was passing by in Rawalpindi. If either attempt had been timed just a little more precisely, Pakistan—and its nuclear arsenal—might now be in the hands of Islamic extremists.

So what are his prospects?

Uncertain. Nearly bankrupt when Musharraf took over, Pakistan’s economy—with lots of U.S. financial help—has made strides. But the democracy picture is murky at best. In a referendum last April, Musharraf won a five-year extension of his presidency with 98 percent of the vote—a result human-rights groups called a sham. But in late December, under a deal reached with a coalition of hard-line Islamic parties, Musharraf agreed to step down as military chief by the end of 2004, while keeping political leadership of the country. Much of the Muslim world continues to see him as a traitor, because of his alliance with the U.S. Musharraf is in a “battle for the heart and soul of Pakistan,” said Chris Smith, a British military scholar. “He’s either going to win big or lose big.”

The big ‘What if?’

The New York Times

-

Political cartoons for February 14

Political cartoons for February 14Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include a Valentine's grift, Hillary on the hook, and more

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

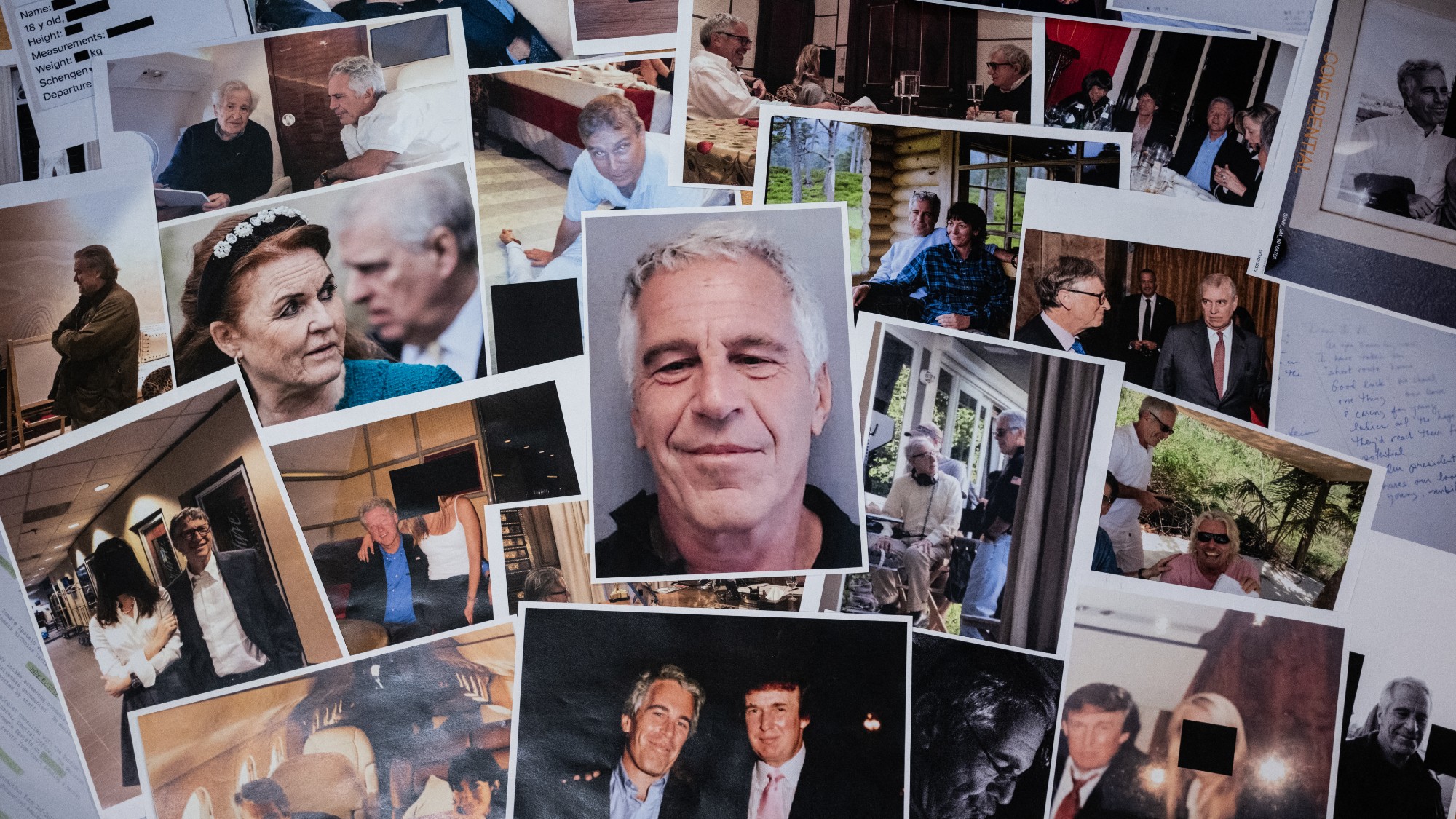

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing world

The Epstein files: glimpses of a deeply disturbing worldIn the Spotlight Trove of released documents paint a picture of depravity and privilege in which men hold the cards, and women are powerless or peripheral