Pro tip for the eurozone: Give Greece's Syriza what it wants

The country's new prime minister is calling for a change

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Syriza, a left-wing party, won a resounding victory in Greek elections over the weekend, running on a platform to roll back a vicious austerity program imposed by eurozone elites. Now the leaders of the eurozone must choose whether they will respect the will of Greek voters or double down on an austerity regime that has crippled the Greek economy.

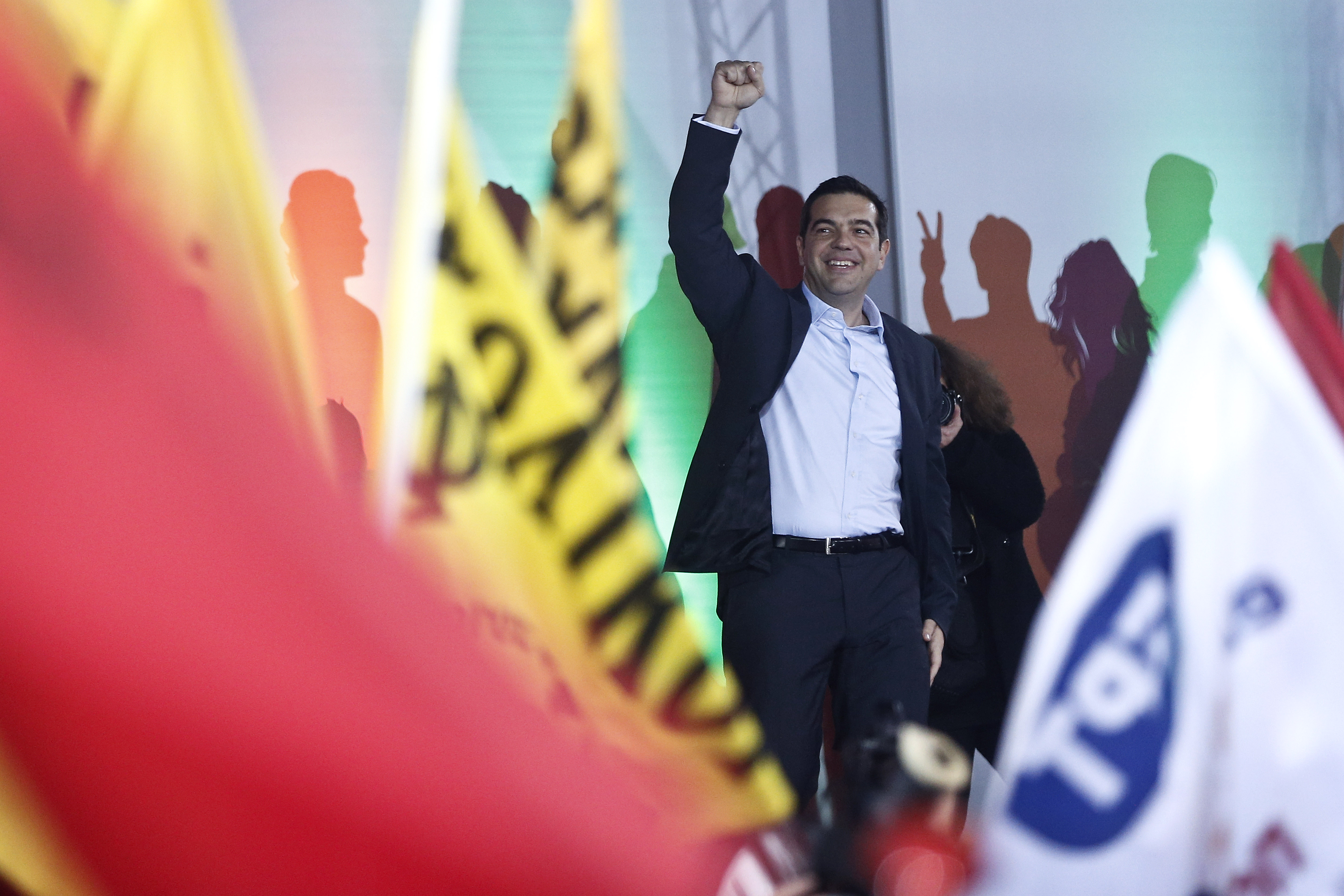

New Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras says his intention is not to leave the euro, but to renegotiate the terms of Greece's austerity package. If they have any sense at all, eurozone elites will give Syriza what it wants.

Recall how we got here: Back in 2010, a newly elected Greek government discovered that previous governments had been cooking the books, and that Greece owed far more to its creditors than was thought. Running out of cash, the Greeks asked for a loan to avoid default.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The eurozone "troika" — the IMF, the European Commission, and the European Central Bank — had the money. But the troika, led by German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the French, strongly disliked the idea of bailing out the Greeks. So in exchange for the loan it mandated sharp tax hikes, severe spending cuts, and a hollowing-out of the public sector — the equivalent of beating the Greek economy senseless with a pipe wrench.

Austerity turned out to be a colossal failure. The Greek economy fared far, far worse than the troika predicted, with the unemployment rate tripling its forecast. Meanwhile, Greece's debt burden has actually gotten worse, not better. Thus, Syriza wants a partial debt cancellation and more breathing room to set its own fiscal policy. It's bog-standard macroeconomic policy.

More than anyone else, the Germans should be sympathetic. In the 1953 London Debt Agreement, West Germany got a colossal package of debt relief. The Germans had decided, as a show of good faith, to pay back some of the World War I–era debts they had defaulted on. But that debt, combined with some large reconstruction loans from the immediate postwar period, threatened to strangle their economy. Creditor nations got together, and West Germany was handed a cool 50 percent debt cancellation.

Furthermore, the Germans even got a clause saying that remaining repayments would be paid out of a maximum of 3 percent of trade surplus earnings — thus further strengthening their economy by incentivizing the purchase of German exports.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Of course, that bargain was mostly about Cold War politics. West Germany was needed as a strong bulwark against the Communist bloc, and so it was patched up without a fuss. But it also reflected a general understanding that demanding too much money from a nation, regardless of the merits of the debt's origins, could destroy its economy and poison its politics.

The creditors would have been perfectly within their rights to demand that Germany pay all it could and then some, since the Germans had just recently started the bloodiest war of all time. But they recognized that this vindictive logic — that of the Treaty of Versailles — was blinkered. Better to keep nations stable and prosperous, and risk someone getting away with malfeasance, than burn economies to the ground on principle. That's how you get fascism.

That lesson — taught by Keynes in 1919, when he howled himself hoarse arguing that Versailles would instigate an apocalyptic war — has been largely forgotten. German policymakers insist that the integrity of Greek debt is paramount:

"The Greeks have the right to elect whoever they want; we have the right to no longer finance Greek debt," Hans-Peter Friedrich, a senior member of Merkel’s conservative bloc, told the daily newspaper Bild on Monday. "The Greeks must now pay the consequences and cannot saddle German taxpayers with them." [New York Times]

This is simply a really stupid way of looking at the problem. Many eurozone nations, including Greece, are in full-blown depression. If your house is on fire, first you put out the fire, then worry about who should pay what.

As in 1953, sometimes it's best for everyone to just wipe the slate clean and have a do-over. Carping about "moral hazard" to a country with an unemployment rate of 26 percent, the vast majority of whom did nothing to create the current disaster, is a failure of political leadership that will only hasten the euro's demise.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Mixing up mixology: The year ahead in cocktail and bar trends

Mixing up mixology: The year ahead in cocktail and bar trendsthe week recommends It’s hojicha vs. matcha, plus a whole lot more

-

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probe

Labor secretary’s husband barred amid assault probeSpeed Read Shawn DeRemer, the husband of Labor Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer, has been accused of sexual assault