How we turned Mount Everest into a dump

Littered with discarded equipment, corpses, and human excrement, the world’s highest mountain is now a dump

Why is Everest so dirty?

Everest has gone from being the ultimate challenge for the most-skilled mountaineers to a bucket list item for adventure seekers. Every year hundreds of climbers try to scale the 29,029-foot peak, and this huge influx of climbers has left its once pristine slopes covered in garbage, discarded equipment, and human waste. A recent report by Grinnell College estimated that 12 tons of feces are left on the mountain each year, either buried in the snow around the four camps near the peak or deposited in rudimentary toilets that are emptied near water supplies further down. An estimated 50 tons of garbage — from broken tent frames to used oxygen canisters to food wrappers — are strewn along the route up the mountain, along with many of the frozen, half-buried corpses of the more than 200 climbers who have perished attempting the ascent. Little wonder the mountain has earned the nickname World's Highest Garbage Dump.

Is anyone trying to clean it up?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Last year, the Nepali government began requiring each climber to bring back at least 17.6 pounds of trash or lose his or her $4,000 deposit — although there are questions about how strictly that rule is enforced. Several expedition companies organize voluntary cleanup trips and offer Sherpas, the local mountain guides, cash rewards for bringing down extra rubbish. In 2013, a joint Indo-Nepali army expedition collected an impressive 4.4 tons of trash in just six weeks; more than half was classified as "biohazardous waste." Sherpas are now finding less trash to bring back, which suggests cleanup efforts are working. But "there is no way to say how much garbage is still left," says veteran guide Dawa Steven Sherpa. "It is impossible to say what is under the ice."

How many people climb Everest?

More than 4,400 climbers have reached the peak since Edmund Hillary and his Sherpa, Tenzing Norgay, first "summited" it in 1953 — most of them very recently. In 2013 alone, Everest was climbed by 658 people during the yearly two-month climbing window in spring. The previous year, 234 climbers reached the peak on a single day. As a result, the top of the world has a serious overcrowding problem. Long lines form below the toughest climbing spots, and Sherpas have even considered erecting a ladder to ease congestion at the Hillary Step, the iconic final obstacle before the summit. Climbing Everest, says mountaineer and author Graham Hoyland, "isn't a wilderness experience. It's a McDonald's experience."

Who are all these climbers?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Many of them are tourists, not true mountaineers. Sherpas spend weeks before each climbing season setting up ropes, ladders, and other equipment along the route to make it easier to ascend. As a result, anyone with a bit of training and in decent shape can climb Everest — provided, of course, they pay from $30,000 to $100,000 per person to an expedition company. Advances in equipment and weather forecasting have also significantly improved success rates: In 1990, only 18 percent of climbers made it to the top; by 2012, it was 56 percent. While the Nepali government has encouraged this dramatic influx — it makes more than $3 million a year from the $11,000-a-head climbing permits — overcrowding on steep slopes 20,000 or 25,000 feet high carries very real dangers.

What sort of dangers?

When climbers have to stand in line for as long as two hours, they waste precious body heat and valuable oxygen supplies. Larger groups usually have to be roped together — meaning if one person falls, and the safety ropes fail, everyone else goes down, too. For Sherpas, who spend so much time on the mountain preparing the routes, the risk is heightened. Last year, an avalanche on the notoriously dangerous Khumbu Icefall killed 16 Sherpas — the deadliest accident in Everest's history. The Nepali government's underwhelming response to the tragedy — offering the victims' families just $400 each in compensation — prompted the Sherpas to end the climbing season early and sparked a debate on their pay and working conditions. But in a region where the only real alternative to mountaineering work is subsistence farming, the stakes are high. "No mountaineering means no tourists," Nima Doma Sherpa, the wife of one of the victims, told The Wall Street Journal. "No tourists means no jobs."

How can Everest be made safer?

Nepali officials have changed the route up the mountain this season to avoid the treacherous Khumbu Icefall. There have been calls for all Sherpas to be given an avalanche beacon, a $300 device that helps rescuers find buried climbers. Ultimately, climbing the world's highest peak — with its deep crevasses and fragile ice towers — will always be a dangerous pursuit. But despite the risk, not to mention the garbage, there will never be a shortage of willing adventurers. "I don't think Everest has that sense of the unknown anymore," says British climber Adele Pennington. "But it still has that majesty. There is still something about standing on top of the world."

Sushi and white wine, please

During their historic ascent of Everest, Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay survived on sardines, dates, and tinned apricots. Today's climbers can pay to enjoy a much higher degree of luxury while conquering nature. At base camp, 17,598 feet up the mountain, high-end expeditions offer yoga classes, sushi, and bars fully stocked with wine, beer, and liquor. On the peak, there is even enough cell reception for climbers to send a celebratory tweet. When last year's tragic Khumbu Icefall avalanche left a section of the mountain all but impassable, a wealthy Chinese businesswoman provoked uproar by paying for a helicopter to ferry her and her team of Sherpas above the accident site. Before his death in 2008, Hillary himself lamented the commercialization of Everest. "Having people pay $65,000 and then be led up the mountain by a couple of experienced guides," he said in 2003, "isn't really mountaineering at all."

-

Magazine printables - January 16, 2026

Magazine printables - January 16, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine printables - January 16, 2026

-

Can Trump make single-family homes affordable by banning big investors?

Can Trump make single-family homes affordable by banning big investors?Talking Points Wall Street takes the blame

-

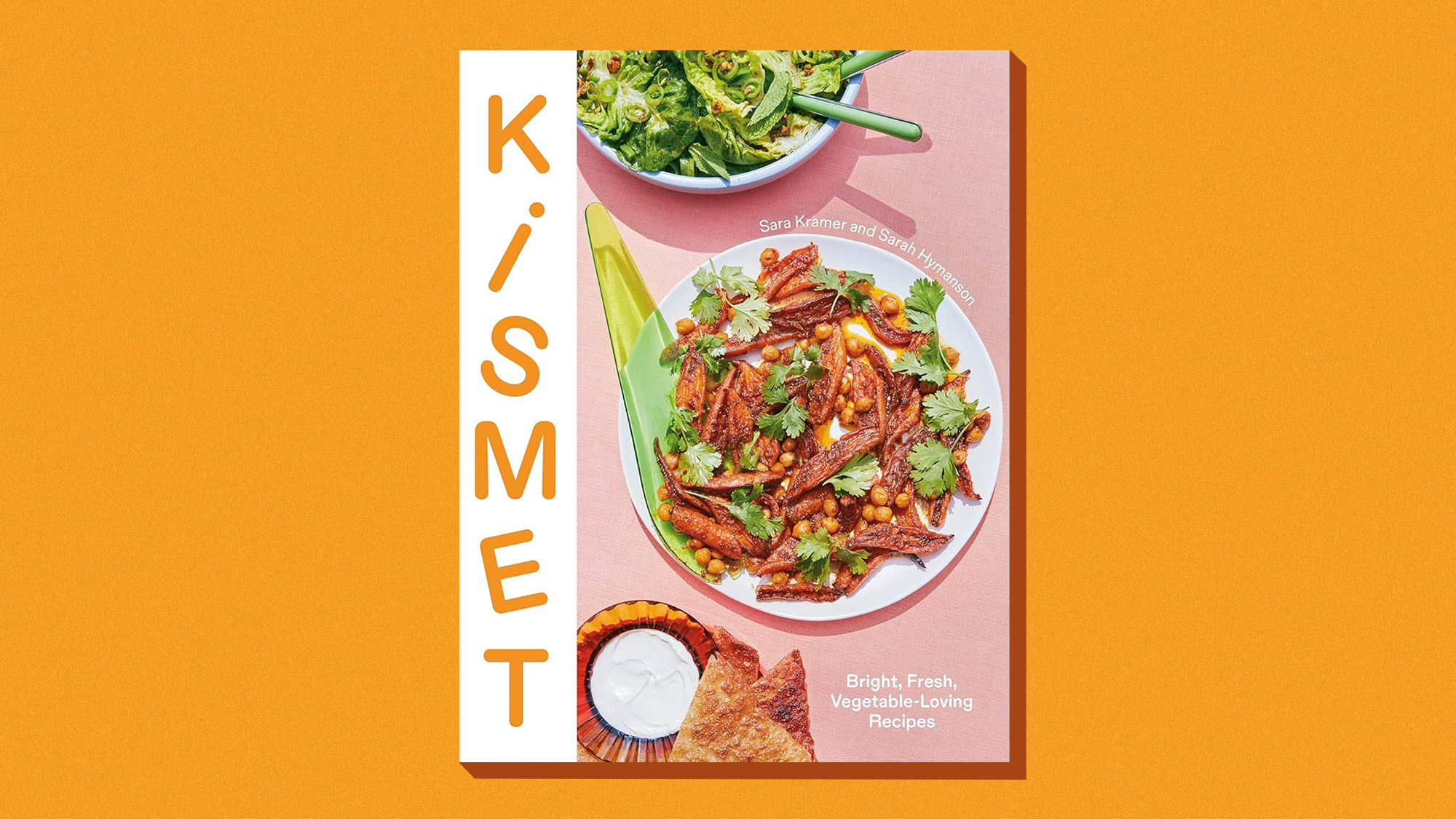

One great cookbook: ‘Kismet: Bright, Fresh, Vegetable-Loving Recipes’

One great cookbook: ‘Kismet: Bright, Fresh, Vegetable-Loving Recipes’the week recommends The beauty and wonder of great ingredients and smart cooking