Monica Lewinsky and the lasting price of shame

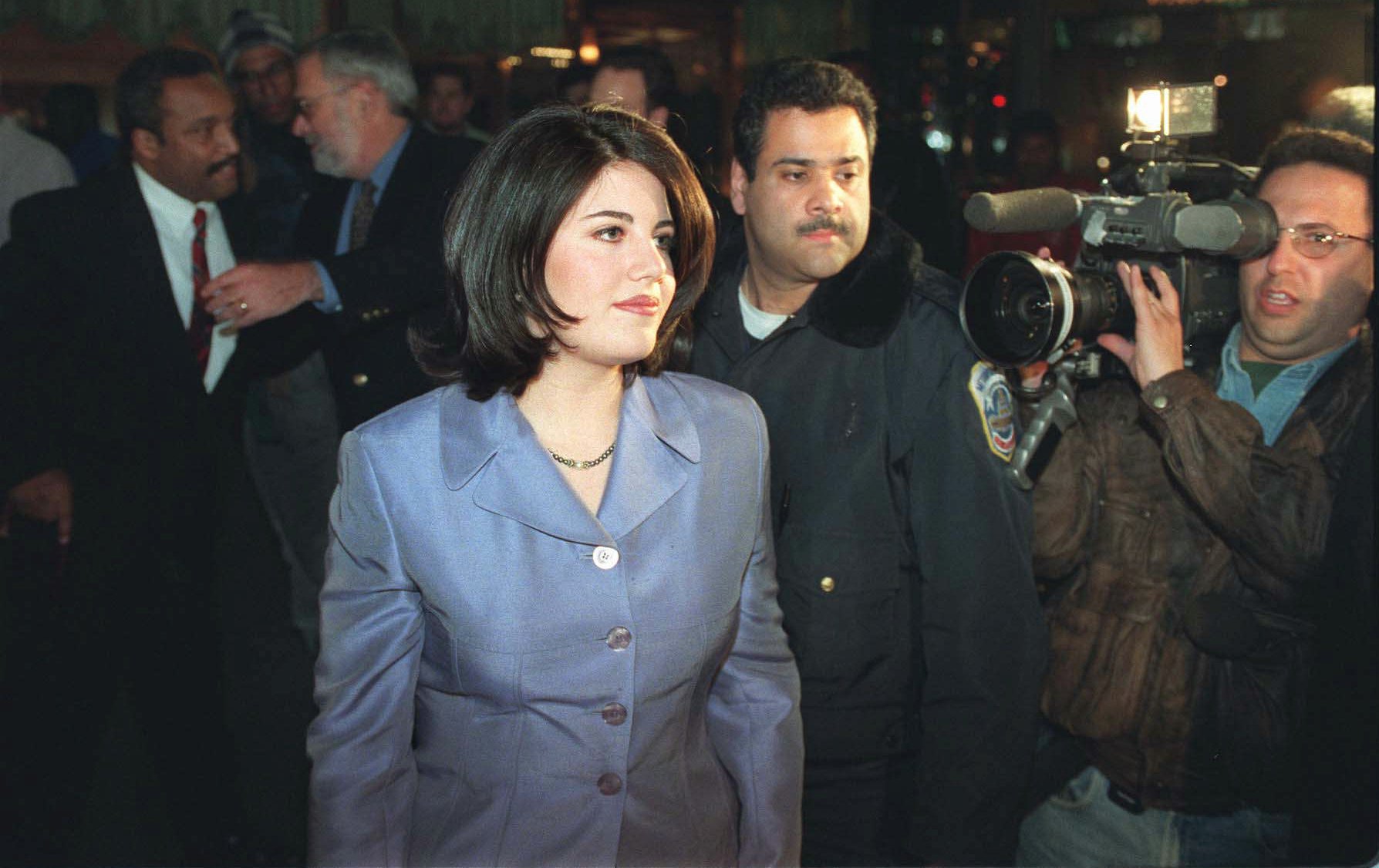

Monica Lewinsky barely survived her humiliation. Now she's teaching what she learned.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

MONICA LEWINSKY WAS sitting in a Manhattan auditorium several weeks ago watching teenage girls perform a play called Slut. She was wiping away tears.

In the scene, a young woman was seated in an interrogation room. She had been asked to describe, repeatedly, what had happened on the night in question — when, she said, a group of guy friends had pinned her down in a taxi on the way to a party and sexually assaulted her. She had reported them. Now everyone at school knew; everyone had chosen a side. "My life has just completely fallen apart," the girl said, her voice shaking. "Now I'm that girl."

The play concluded, and Lewinsky fumbled through her purse for a tissue. A woman came and whisked her to the stage.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Hi, I'm Monica Lewinsky," she said, visibly nervous. "Some of you younger people might only know me from some rap lyrics."

The crowd, made up largely of high school and college women, laughed. "Monica Lewinsky" is the title of a song by rapper G-Eazy; her name is a reference in dozens of others: by Kanye, Beyoncé, Eminem.

"Thank you for coming," Lewinsky said, "and in doing so, standing up against the sexual scapegoating of women and girls."

Asked later about the play, Lewinsky said, "It's really inspiring to hear people bring awareness to this issue. That scene in the interrogation room was hard to watch. One thing I've learned about trauma is that when you find yourself retriggered, it's helpful to recognize when things are different."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A LOT IS different for Lewinsky these days, starting with the fact that until last year, she had hardly appeared publicly for a decade. Now 41, the former White House intern, once famously dismissed by the president as "that woman," holds a master's degree in social psychology from the London School of Economics.

She splits her time between New York City and Los Angeles, where she grew up, and London, and said it's been hard to find work. Mostly she has embraced a quiet existence: doing meditation and therapy, volunteering, spending time with friends.

She is stuck in a kind of time warp over which she has little control.

But the quiet ended last May, when she wrote an essay for Vanity Fair about the aftermath of her affair with President Bill Clinton. In this essay, which was a finalist for a 2015 National Magazine Award, she declared that the time had come to "burn the beret and bury the blue dress" and "give a purpose to my past."

That new purpose, she wrote, was twofold: it was about reclaiming her own story — one that had seemed to metastasize — but also to help others who had been similarly humiliated. "What this will cost me," she wrote, "I will soon find out."

It hasn't appeared to cost her, at least not yet. In fact, the opposite has occurred.

Over the past six months, she has made appearances at a benefit hosted by the Norman Mailer Center (she and Mailer had been friends), at a New York Fashion Week dinner presentation for designer Rachel Comey, at the Vanity Fair Oscar party, and as her friend Alan Cumming's date at an after-party for the Golden Globes.

Perhaps most interestingly, in October, onstage at a Forbes conference, she spoke out for the first time about the digital harassment (or cyberbullying) that has affected everyone from female bloggers to Jennifer Lawrence to ... her: "I lost my reputation. I was publicly identified as someone I didn't recognize. And I lost my sense of self," she told the crowd.

She just took that declaration one step further last month on the main stage at TED in Vancouver, British Columbia, where she issued a biting cultural critique about humiliation as commodity. The title of her 18-minute talk (and, perhaps, the line that best sums up her experience), which received a raucous standing ovation, was "The Price of Shame."

THIS IS NOT Lewinsky's first attempt at reinvention. She's also not the Lewinsky of more than a decade ago, the one who created a handbag line and tried her hand at reality TV.

This iteration is a bundle of contradictions. Warm yet cautious. Open yet guarded. Strong but fragile. She is likable, funny, and self-deprecating. She is acutely intelligent, something for which she doesn't get much credit. But she is also stuck in a kind of time warp over which she has little control.

At 41, she doesn't have many of the things that a person her age may want — a permanent residence, an obvious source of income, a clear career path. She is also very, very nervous. She is worried about being taken advantage of, worried her words will be misconstrued, worried reporters will rehash the past.

She is prepared, almost always, for doomsday: the snippet of a quote that might be taken out of context; questions about the Clintons, whom she declines to discuss. "She was burned ... in myriad ways," said her editor at Vanity Fair, David Friend.

Lewinsky wouldn't call this a reinvention. This, she says, is simply the Monica who — despite the headlines, despite the incessant paparazzi-style coverage — "was seen by many but truly known by few," as she put it on the TED stage. "This is me," she told me. "This is a kind of evolution of me."

It was like reading a really wonderful dirty book, except it was her story.

I had approached her after the Vanity Fair essay in part because I was intrigued but also because I had a tinge of guilt. I had come of age in the Lewinsky era. I distinctly remember my high school self, wide-eyed, poring over the soft-core Starr report with friends. None of us had the maturity to understand the complexities, or power dynamics, of the president's affair with a young intern. When I was 16, one dominating image of Lewinsky seemed to overshadow all others: slut. Of course, that 22-year-old intern was only a few years older than I was.

And so I emailed her. I told her I was interested in her effort to re-emerge and had been particularly fascinated by the reaction to it, as if there were a kind of public reckoning underway. Feminists who had stayed silent on the first go-round were suddenly defending her, and using terms like "slut shaming" and "media gender bias" to do it.

Late-night host David Letterman was on the air expressing remorse over how he had mocked her, asking, in a recent interview with Barbara Walters, "With some perspective, do you realize this is a sad human situation?" Bill Maher said of reading Lewinsky's piece in Vanity Fair, "I gotta tell you, I literally felt guilty."

"However you felt about the actual event, the way it played out was pretty grotesque," said Rebecca Traister, a senior editor at The New Republic who was just out of college when the Clinton scandal broke and who wrote about it later.

Traister said she was taken aback when she reread her own 2003 article, "Get Off Your Knees, Monica." "Whether it's guilt, or sophistication, or thinking a little harder about sexual power dynamics, I think people have started to think: ‘Oh, right, she probably does have a right to tell her story. And that's a good thing.'"

This time, Lewinsky appears determined to tell it on her terms. She has a P.R. agent screening requests and approaches media as one may expect: with the caution of a woman who has been raked over the coals.

I MET LEWINSKY at her apartment, where she was rehearsing her TED speech in front of a small metal music stand.

She handed me a script. "It's changed a bit, so you can follow along," she said. (By the time she appeared onstage at TED, in front of a packed room, she was on Version 24.)

She was working through the middle of the speech, where she would describe her questioning by investigators. It was 1998, and she had been required to authenticate the phone calls recorded by her former friend Linda Tripp. They would later be released to Congress.

She glanced at the script, and then looked forward. "Scared and mortified, I listen," she said. "Listen to my sometimes catty, sometimes churlish, sometimes silly self, being cruel, unforgiving, uncouth..."

"Listen, deeply, deeply ashamed, to the worst version of myself." She paused. "A self I don't even recognize." Lewinsky doesn't have a speechwriter; she wrote the speech herself.

She went back and forth over the opening, a joke about a man 14 years her junior, who hit on her after she spoke at Forbes. "What was his unsuccessful pickup line?" she would ask rhetorically. "He could make me feel 22 again. Later that night, I realized: I'm probably the only person over 40 who would not like to be 22 again."

"Can I see a show of hands," she would ask, "of anyone who didn't make a mistake or do something they regretted at 22?"

TED approached Lewinsky about speaking at the conference, whose theme this year was "Truth and Dare," after watching her Forbes speech. The speech's theme had been marinating for years. In graduate school, Lewinsky had studied the impact of trauma on identity.

Then Tyler Clementi, a Rutgers freshman, killed himself after being recorded by his college roommate being intimate with a man. It was 2010, and Lewinsky's mother was beside herself, "gutted with pain," as Lewinsky said onstage, "in a way I couldn't quite understand."

Eventually, she said, she realized that to her mother, Clementi represented her. "She was reliving 1998," she said, looking out over the crowd. "Reliving a time when she sat by my bed every night. Reliving a time when she made me shower with the bathroom door open."

She paused, becoming emotional. "And reliving a time both my parents feared that I would be humiliated to death."

"It was easy to forget," she said, "that 'that woman' was dimensional, had a soul, and was once unbroken."

THE WAY LEWINSKY tells it, she was Patient Zero for the type of internet shaming we now see regularly. Hers wasn't the first case ever, but it was the first of its magnitude. Which meant that virtually overnight, she went from being a private citizen to, as she put it, a publicly humiliated one.

"She couldn't go to a restaurant and order a bowl of soup — literally — without it being reported the next day," said Walters. The story was the perfect combination of politics and sex. "It was like reading a really wonderful dirty book," Walters said, "except it was her story."

It was before the days of the internet sex tape, but barely. Princess Diana had been photographed with a hidden camera while working out at the gym; Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee's honeymoon sex tape was stolen from their home and bootlegged out of car trunks. "It was at the tip of the spear of this invasive culture," said David Friend.

Lewinsky was quickly cast by the media as a "little tart" — as The Wall Street Journal put it. The New York Post nicknamed her the "Portly Pepperpot." She was described by Maureen Dowd in The New York Times as "ditsy" and "predatory."

And other women — self-proclaimed feminists — piled on. "My dental hygienist pointed out she had third-stage gum disease," said Erica Jong. Betty Friedan dismissed her as "some little twerp."

"It's a sexual shaming that is far more directed at women than at men," Gloria Steinem wrote me in an email, noting that in Lewinsky's case, she was also targeted by the "ultraright wing." "I'm grateful to (her)," Steinem said, "for having the courage to return to the public eye."

Earlier, I had asked Lewinsky what she hoped to accomplish with a platform like TED. She asked if I had read David Foster Wallace's Brief Interviews With Hideous Men. In it, there is a chapter about suffering and the story of a girl who survives abuse.

What the young woman endures is horrific, said Lewinsky, but by going through it, she learns that she can survive.

"That's part of what I thought I could contribute," she said. "That in someone else's darkest moment, lodged in their subconscious might be the knowledge that there was someone else who was, at one point in time, the most humiliated person in the world. And that she survived it."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The New York Times. Reprinted with permission.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal