Why I'm glad I gave up my dream of going to law school

We can't all be Elle Woods

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For years, I was dead-set on going to law school. And not just any law school — Harvard. But midway through college, I was forced to confront this plan I had for myself. I asked myself why I really wanted it, and how much I was willing to sacrifice for it.

I realized I wasn't willing to sacrifice much, and that my dream may have been a convenient aspiration — one that ultimately hindered my pursuing less conventional career paths that would have better suited me.

Why did I want to be a lawyer in the first place? I'm not particularly proud of this, but I blame Legally Blonde. Elle Woods was spunky, smart, and accomplished, and when I was 10 years old, I wanted to be just like her. (To this day, I keep a blonde Chihuahua sidekick).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In high school, I began telling people that I wanted to be a lawyer. As a student whose best subjects were English and history, it was a logical progression of my studies. Plus, pursuing law seemed like a reliable career path with well-defined milestones (take the LSAT, go to law school, pass the bar exam, get a job at a firm, become a partner) that my parents and I would both be proud of. It was prestigious, respectable, and familiar, like a good handshake.

But at the time, I never really examined why I was so all-in on becoming a lawyer. Once I declared I wanted to be a lawyer, I simply organized the rest of my life around getting there. It was a bar I had to hurdle, and I was going to figure out how to do it.

When I was applying to colleges, I kept up with the law school theme, selecting political science as my intended major because I assumed that's what pre-law students did. I got to college, took undergraduate law classes, and did well in them. I was mainly interested in criminal law, and I genuinely enjoyed it: The material we studied was bizarre and fascinating — like one case where a man was acquitted of murder on a sleepwalking insanity defense, and another where a man was arrested for drunk driving after he was home, asleep in his bed. It was probably the only course in which I did the required reading prior to class. I would sit in the front row, eagerly answering questions and offering opinions about the cases, countering the justices' decisions due to this or that precedent. I even started writing for a political magazine, where our staff covered everything from Supreme Court cases to rap music's effect on economic policy. I was surrounded by peers I considered brilliant, and they pushed me to develop the critical thinking skills that were surely a core part of being a litigator. I was confident I was on the right track.

And yet, I began to have inklings of doubt. Nearly every professor in my political science classes would use the first day of class to ask how many of us wanted to be lawyers; he would then launch into a speech about why this was a terrible career choice given the law school bubble (which has since popped).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

I tried not to let it get me down. Sure, I was on a pre-law track at a time when high percentages of law grads were struggling to find employment, but I shouldn't be deterred, I thought. I'm ambitious. I'm a hard worker. I'm not daunted by a challenge.

This ambition clouded my judgment. It made it easy for me to keep working toward my predetermined goal of law school without ever really stopping to think about why I wanted to become a lawyer in the first place.

Finally, something in me snapped. Part of it was finally confronting the terrifying reality of taking out massive six-figure loans to finance law school. But more than that, it was the anecdotes from my jaded ex-lawyer professors, who described what daily life as a lawyer would actually be like. They described miserable 60-hour work weeks in huge firms where no one cares about you. They warned us that being a lawyer isn't all sweeping Atticus Finch speeches. There are countless thankless, painstaking tasks, grueling research, and all kinds of things that sounded pretty terrible to me when I actually stopped to think about them.

It shattered my conception of what it might be like to be a lawyer. It forced me to really evaluate why I wanted this dream in the first place. It made me confront all the negative things about the profession I had previously brushed off as mere obstacles. Suddenly, I imagined myself as a young lawyer, fresh out of school and recently licensed, doing the work my professors described. I didn't like what I saw.

I realized that I had wanted to be a lawyer for all the wrong reasons; for the prestige and the respect. I wanted people to know I was smart and confident and successful. But when it came down to it, I realized I could show people I was smart and successful in another way — one that would likely make me happier.

At first, it was hard to give up the idea of law school. I felt like I had failed in a way, even though all I really did was change my mind. But at the same time, I felt free. It was a relief not to be locked into a plan I didn't really want.

Stephanie is an editorial assistant at TheWeek.com. She has previously worked for USA Today and Modern Luxury Media.

-

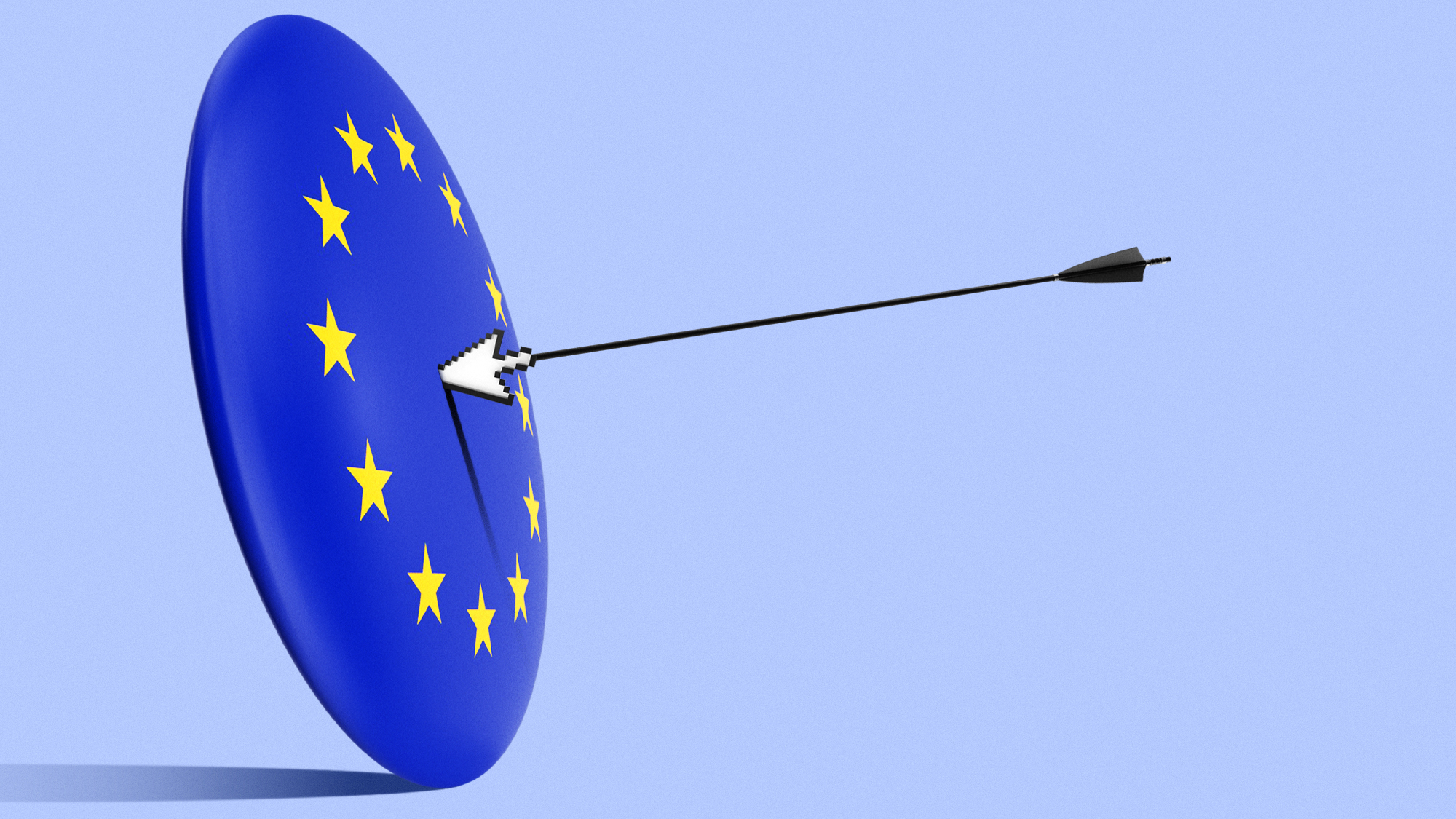

Can Europe regain its digital sovereignty?

Can Europe regain its digital sovereignty?Today’s Big Question EU is trying to reduce reliance on US Big Tech and cloud computing in face of hostile Donald Trump, but lack of comparable alternatives remains a worry

-

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to Starmer

The Mandelson files: Labour Svengali’s parting gift to StarmerThe Explainer Texts and emails about Mandelson’s appointment as US ambassador could fuel biggest political scandal ‘for a generation’

-

Magazine printables - February 13, 2026

Magazine printables - February 13, 2026Puzzle and Quizzes Magazine printables - February 13, 2026