Is there a bubble in digital media? On NBCUniversal's deal with BuzzFeed.

Investors have been plowing money into online media properties. But it's far from clear that they're worth it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

NBCUniversal is poised to dump a big, heaping pile of cash into BuzzFeed and Vox Media, two online outlets that embody the new world of digital media and news.

BuzzFeed began as the internet's go-to source for kitten gifs, then moved into serious and long-form journalism. Vox Media, meanwhile, oversees a swarm of digital outlets, including The Verge, Polygon, and most recently Vox, the news site led by Washington Post alum Ezra Klein. As of last year, BuzzFeed was valued at $850 million, and Vox Media at $380 million.

On Wednesday, Kara Swisher and Peter Kafka reported in Re/code (also owned by Vox Media) that the NBCUniversal deal would raise BuzzFeed's valuation to $1.5 billion, and Vox Media's to $850 million. The Vox arrangement is still in negotiations, while the $250 million investment in BuzzFeed is in the "handshake" phase.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

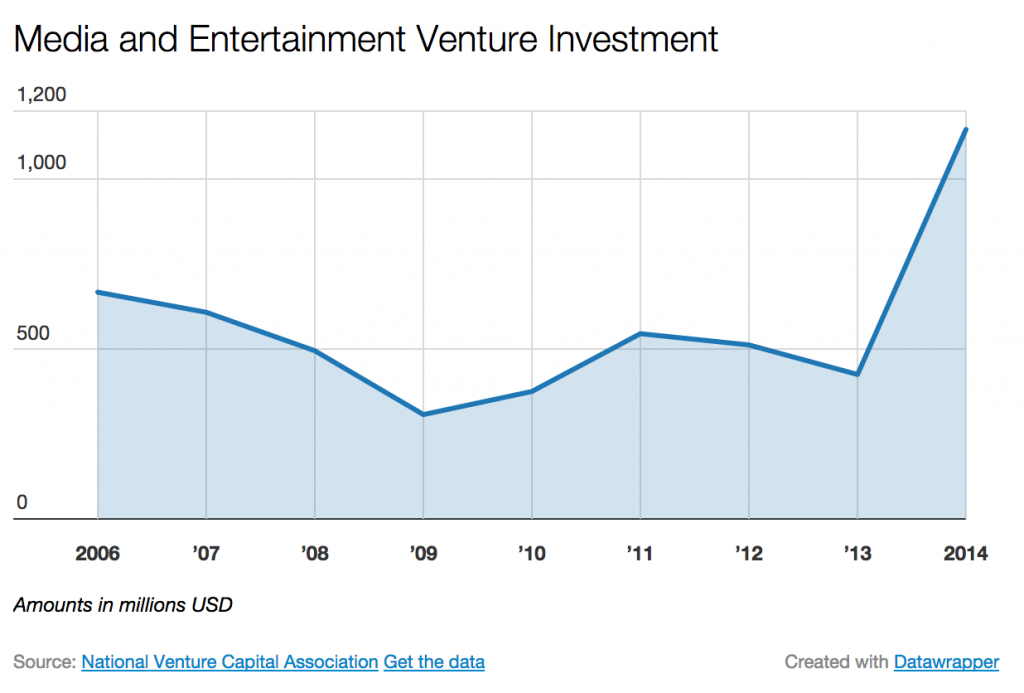

NBCUniversal is the film and television arm of the behemoth cable operator Comcast, and this isn't the only recent instance of a traditional media operator plowing hundreds of millions into the digital media arena. Last year, the cable programmer A&E invested $250 million in Vice Media, and in May Verizon bought out AOL wholesale. Venture capital has also been pouring into Vox Media, BuzzFeed, and other online media sites like Business Insider, producing a remarkable boom in investments since 2013:

(Graph courtesy of Doremus.)

Not surprisingly, fears of a bubble in digital media are percolating. Digital media companies were "once thought to be toxic to investors," Swisher and Kafka wrote. "But the notion that these companies are the equivalent of cable TV networks like ESPN in the early 1980s — rough around the edges now, and incredibly valuable 10 and 20 years later — has become fashionable in some parts of the media world."

It probably goes too far to say that a bubble can only be spotted after it bursts, but there's a certain truth there: Investment is by definition risk, and taking a risk is by definition an act whose pay-off cannot be foreseen. Henry Blodget, who runs Business Insider, is skeptical a bubble is what we're seeing. "CNN is worth $11 billion. There are going to be digital-media companies that are worth $10 billion in 10 years, 20 years," he told New York Magazine the other day.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Maybe. The problem is it's hard to see — practically speaking — how this particular business model is supposed to justify those kinds of sky-high valuations. Keep in mind these sites have all turned away from charging users for access to content, for the most part. That leaves advertising as the main source of revenue. There's certainly nothing new about that, but back in the old days when media was still all print, getting advertisements into a magazine or newspaper and churning out thousands upon thousands of physical copies came with significant costs. Those costs in turn made selling advertisement space a viable and robust income stream: There was only so much space to go around, so advertisers valued it, and publications didn’t have to bend over backwards to keep themselves in the black.

But the digital revolution has made the space for advertisements nearly infinite, and pushed the costs of creating and distributing those advertisements close to zero. (Moving around electrons is an exceedingly cheap business.)

It's important to remember that digital outlets' customers aren't the readers, they're the advertisers. What digital media is selling advertisers is views, and thanks to the digital revolution, those views are close to becoming a commodity — cheap, ubiquitous, and undifferentiated. Digital outlets now have to make their money selling way more views, or "units" of advertising, each one of which provides far less revenue per unit.

Vox and Business Insider and BuzzFeed and all the rest are in danger of falling into "commodity hell," where there's no way to distinguish yourself from the competition and everyone competes on price alone, driving profits to zero.

Of course, that fate isn't sealed. Facebook seems to be keeping ahead of the problem in the most blunt way possible: by crushing every other social media provider in terms of user numbers. But that's probably not so much a strategy as an unrepeatable fluke of good fortune. In fact, Facebook already seems to be evolving away from a digital company competing with its fellows, and into a platform on which those other companies then compete.

This points to the other ways companies could escape commodity hell. Some unforeseen innovation in advertising or digital technology could always restructure the market. But the more interesting innovations are the non-technological kind: changes in product or approach or business model. BuzzFeed's exploration of nesting content within Facebook and sharing advertising revenue — rather than using Facebook to drive clicks back to its own site — is one possibility. (The New York Times is trying a similar approach.)

Even Business Insider's use of sensationalistic headlines, promising to blow your mind with remarkable reversals of the world you thought you knew, were an innovation of a sort. But that's been commoditized too, as the practice is now everywhere. So Business Insider now appears to be playing with charging users for premium content and research — a hybrid approach other, more established outlets like the Times and The New Yorker are trying on the online side.

In truth, digital media outlets could probably survive just fine with smaller and more specialized readerships, charging for some content, and accepting modest returns. But investors are still in their early, excitable phase, expecting every new outlet to be the next big payout.

Some might pull it off.

Or they might go the way of GigaOm, a tech blog that led the digital media craze, raising $22 million in six rounds of funding over eight years, before it blew apart in March. "Folks, someone getting a lot of VC [venture capital] investment isn't a sign they're successful at anything other than getting VC funding," Danny Sullivan, the founder of Search Engine Land, wrote at the time. "An investment in a company could be a vote a confidence in it, that a VC has made a careful analysis that success is likely.

"Or, it could be a crapshoot."

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.