What the Fed keeps getting wrong about the economy, in one crazy chart

How the Phillips Curve explains the Fed's wrongheaded desire to raise interest rates

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If the chatter out of Jackson Hole is any indication, the recent financial market freak-out over China did not extend to the Federal Reserve.

The Wyoming town played host this weekend to an annual economic symposium, and several of the Fed's big decision-makers were in attendance, including Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer. And while they'll be paying close attention to August's job creation numbers — due this Friday — they seem to see no reason to ditch their plan to begin increasing interest rates sometime this year, perhaps as early as September.

To be fair, it's likely the recent turmoil won't reach down into America's real economy at all. But even if August's jobs numbers are fine, that's no reason for the Fed to start raising rates.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In fact, it's a reason for them not to.

This weekend's symposium was entitled "Inflation Dynamics and Monetary Policy." In plain English, economists have a rule of thumb for how inflation is supposed to behave in recessions and recoveries, and in recent decades inflation's real world behavior hasn't fit the model.

The basic theory behind inflation is this: As jobs become more plentiful and more Americans become employed, businesses can no longer attract new hires by simply offering a job. They have to offer higher salaries, and a society-wide bidding war for workers ensues.

Now, if productivity throughout the economy keeps growing at a fast enough rate — if businesses keep coming up with new ways to deliver the same value at less cost — inflation won't increase. The new money freed up by the productivity increases goes into paying the higher wages for workers.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But if productivity can't keep up, then the only way for businesses to keep paying higher salaries is to hike prices. So a ratchet effect sets in as wage pressure drives up prices throughout the economy — the textbook definition of inflation.

That gives you the relationship economists usually expect to see between inflation and unemployment. As the economy recovers from a downturn and the unemployment rate goes down, inflation should start rising.

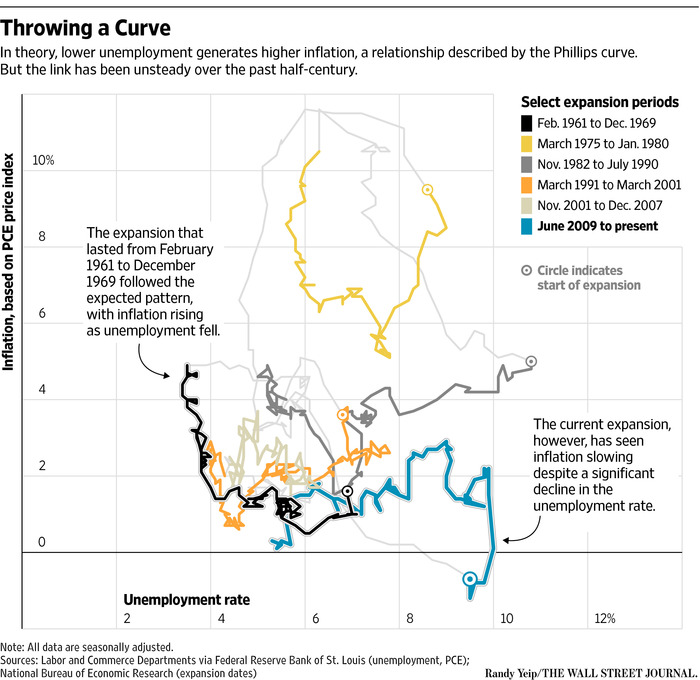

This can be illustrated by a graph called the "Phillips Curve," seen below. It may look like horrifying ball of string. But it's just the inflation rate on the vertical axis, and the unemployment rate on the horizontal axis, and then a plot of where the two intersect. The Phillips Curve is the path that intersection traces over time. And if you look at the black line below — the economic expansion from 1961 through 1969 — it does what economists think it should do: trace an upward sloping curve from right to left, as unemployment drops and inflation picks up.

(Graph courtesy of The Wall Street Journal.)

But the more recent expansions — the orange, tan, gray, and turquoise lines — don't really trace any pattern at all. They're just a relatively flat jumble, with low inflation in times of both high and low unemployment. Ever since the Great Recession, inflation has remained stubbornly at basement levels, nowhere near the Fed's ostensible target rate of 2 percent annually, even as the official unemployment rate has dropped. That really has everyone confused.

May I humbly suggest they shouldn't be?

The unemployment rate isn't the percentage of the country that doesn't have a job, it's just the percentage of the "labor force" that doesn't. This introduces a big hiccup because, as many have noted, the labor force only counts the employed and the people who are unemployed but looking for work. If you're able and willing to work, but the economy has been so bad you've just given up looking for a job, you don't count as part of the labor force at all.

This is a big deal. Human beings are not abstract economic functions. If they go without work too long, they can lose skills, social and professional networks, their marriages, their family and social support, and, yes, their will and spirit. They may be forced to move to a more impoverished area that offers fewer opportunities even as the economy improves. If their abilities lie in physical labor, their bodies may begin to fail them. Recessions do enormous damage to real human lives, and that damage can live on long after a recession has faded.

And in the period of time defined by the malfunctioning Phillips Curve, recessions have been especially bad: Recoveries have been much slower, jobs took much longer to come back, and when they did they paid worse.

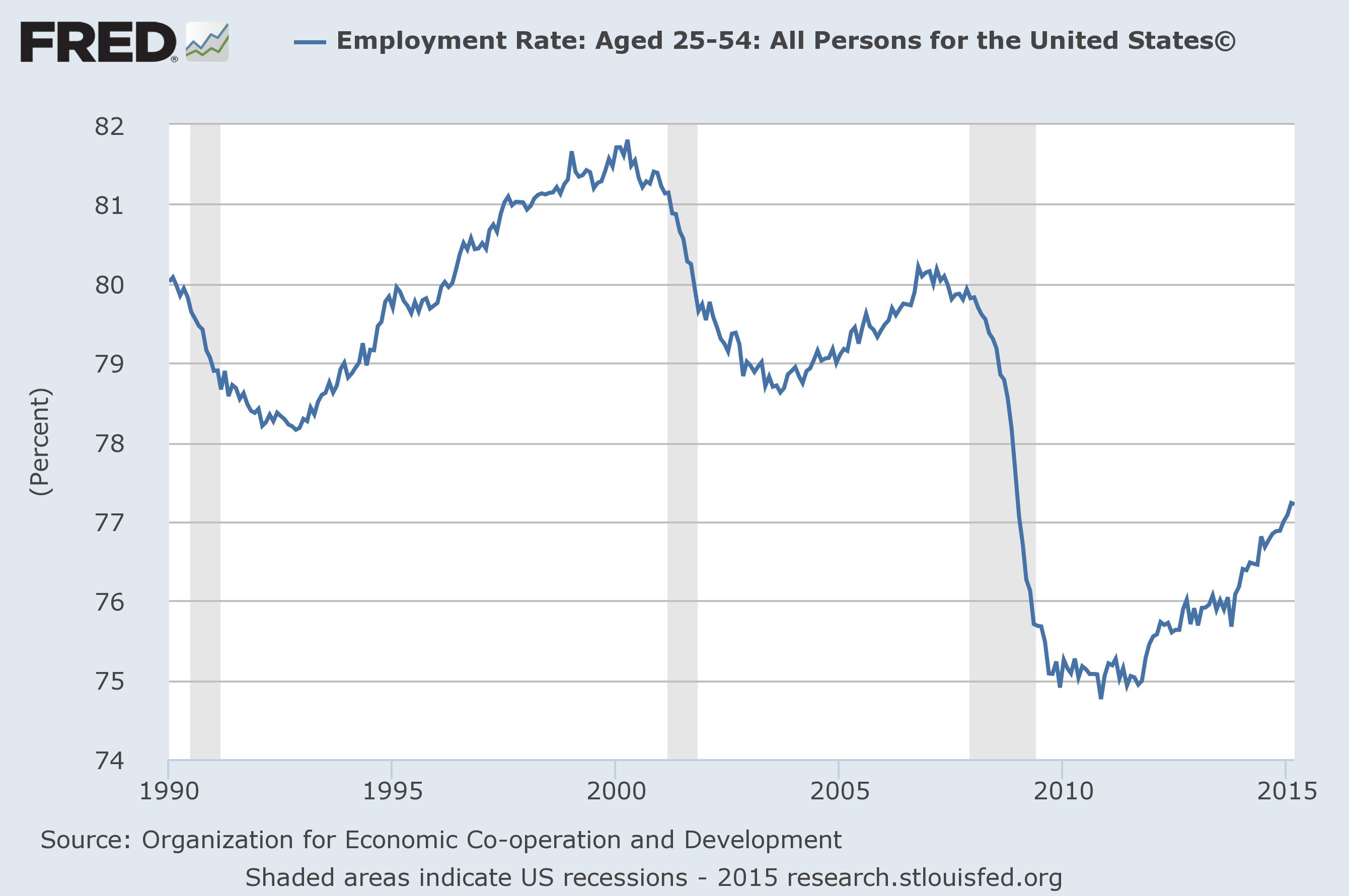

You can see this in the official labor force numbers, which started dropping after 2000 and fell off a cliff after 2008. But people can fall out of the labor force for a lot of reasons; for example, they may respond to a recession by staying in school longer or retiring earlier. So the real tell is the employment rate amongst all Americans age 25 to 54 — too old to be students and too young to retire:

It's at 77 percent, which is below its 2007 peak of 80 percent, which was below its 2000 peak of 81 percent. The prime age labor force is 124.5 million people, and 4 percent of that is almost five million.

That's a lot of workers who are just...missing.

This gets us back to the Phillips Curve. Nothing structural has changed to explain why the natural employment rate for prime age workers should be lower now than in the 1990s. If five million people have dropped out of the labor force because their lives were wrecked by previous downturns, then that's a huge "reserve army" of labor that could potentially be brought back in. In that case, the unemployment rate compared to the official labor force could get very low without inflation rising, precisely because you're still bringing in people who just need a job — any job — rather than higher wages.

Given that the damage from recessions takes time to set in, it's also going to take time to repair it. And the prime age employment rate is improving, slowly but surely. Prematurely hiking interest rates could cut off that process.

So it's encouraging that a popular movement to pressure the Fed to keep interest rates low appears to be gaining steam. At the very least, the Fed should wait until the prime age employment rate is back to 81 percent before it starts hiking. A few years of inflation above 2 percent is a small price to pay to repair millions of livelihoods.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’