Why the independence of central banks is overrated

The past seven years show that we should fear the bureaucrats, not the politicians

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The independence of central banks has long been one of the bedrock principles of orthodox economics. If you let grubby politicians get their hands on the monetary policy levers, then they'll quickly turn any developed country into Zimbabwe. This is because they will always be trying to stoke the economy and reduce unemployment to win the next election — and will be too reluctant to create the recession necessary to strangle inflation.

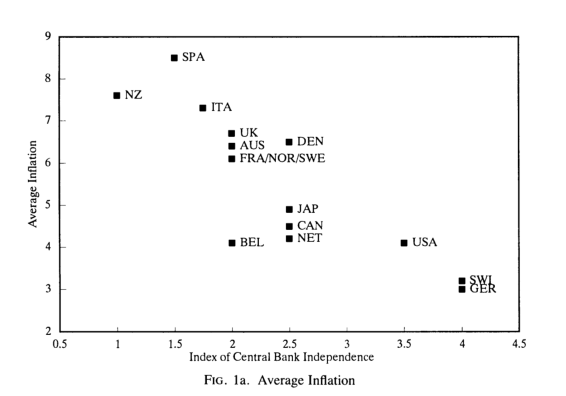

This notion got a huge amount of support from empirical work carried out in the early 1990s, perhaps most famously in a 1993 paper by Alberto Alesina and Larry Summers, which has been cited 1,937 times, according to Google Scholar. (Summers, of course, would go on to head the Treasury Department under Bill Clinton and become one of President Obama's top economic advisers, while Alesina would write a disastrously mistaken 2009 paper supporting fiscal austerity.) Their method was extremely simple: Just take a measure of central bank independence, and plot it against macroeconomic indicators taken from the period 1955-88. They found a smooth relationship between greater independence and lower inflation — and more importantly, no cost at all for unemployment or growth. This was widely promulgated as stark and very-easy-to-understand evidence for the orthodox case.

With several years passed since the onset of the Great Recession, I thought it would be a good time to take a quick and dirty look at Alesina and Summers' metric. Does central bank independence still work like it did back then?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Nope!

So here's the famous chart from the original paper. With that strong and obvious relationship, its easy to see why it has been so influential:

Their other charts plotting central bank independence versus growth or unemployment, by contrast, showed no relationship at all.

Before I get to my updated version, let me admit up front that a lot of things have changed in monetary policy since 1993 (especially the widespread adoption of inflation targeting), but I'm not going to deal with them. While I tried hard to use appropriate and similar datasets at all times, without question this is just a quick sketch, not a rigorously controlled piece of econometrics.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

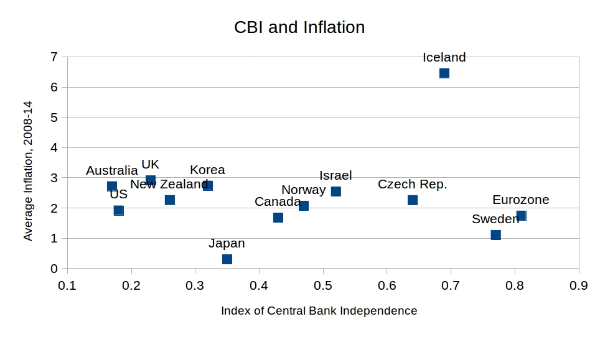

That said, here's central bank independence plotted against inflation since 2008, for as many industrialized nations as I could find:*

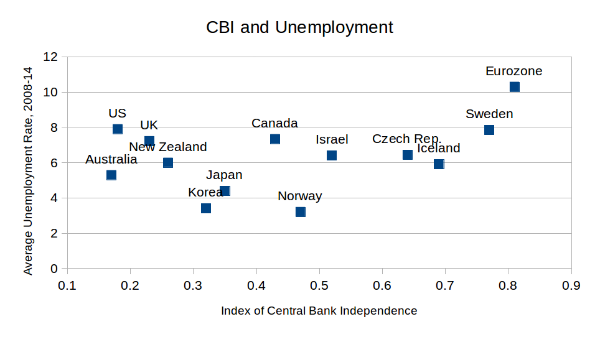

Alesina and Summers' relationship has totally disappeared! Here's unemployment:

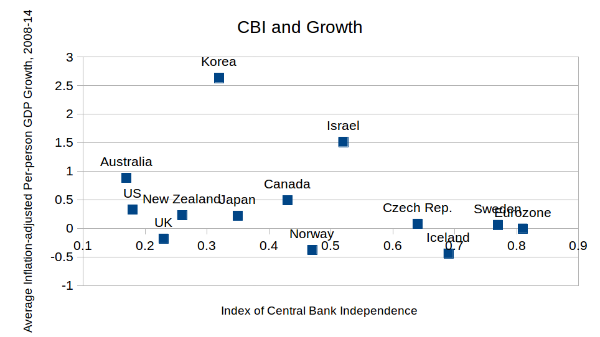

And growth:

Though neither of these latter measures have the same crystal-clear relationship seen in the inflation chart from 1993, there's a pretty clear positive relationship with unemployment, and a negative relationship with growth. The most one could say is that there is little discernible effect either way.

In short, as my colleague Jeff Spross argues, there is little reason to worry about "politicizing" the central bank.

The mind-crushingly abysmal performance of the European Central Bank deserves special mention. When it comes to political freedom, it is in a class by itself. In addition to overseeing a vastly larger economy than any institution save the Federal Reserve, it uniquely enjoys a supranational position, with the ability to execute coup d'etats against recalcitrant Italian prime ministers or dictate fiscal policy to sovereign nations. No other central bank in history has had that kind of power — and the ECB has turned in the kind of steaming garbage you'd expect from an office temp with a bad attitude. Real per capita GDP growth is negative over six years. Unemployment has been over 10 percent for five straight years. Even inflation is below target.

It was always kind of weird to see conservative economists loudly proclaiming the virtues of placing important policy instruments in the hands of unaccountable bureaucrats. But, at least when it comes to fighting world-historical recessions, it turns out that regular old democracy is nothing to fear.

*A note on data sources. Measurement of central bank independence taken from the CBIW table in Dincer and Eichengreen, 2014. Annual averages of inflation were obtained mostly from FRED (Australia, Canada, Iceland, Japan, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Czech Republic, U.K., U.S., eurozone, Israel, South Korea), as well as annual unemployment averages (Australia, Canada, Iceland, Japan, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Czech Republic, U.K., U.S., eurozone, Israel, South Korea) and inflation-adjusted growth of GDP per capita (Australia, Canada, Iceland, Japan, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, Czech Republic, U.K., U.S., eurozone, Israel, South Korea).

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Switzerland could vote to cap its population

Switzerland could vote to cap its populationUnder the Radar Swiss People’s Party proposes referendum on radical anti-immigration measure to limit residents to 10 million

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry