The weird groupthink worsening Puerto Rico's economic crisis

Puerto Rico literally has no good options, but that's only because policymakers are unwilling to think outside the conventional wisdom

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Puerto Rico, as you may have heard, is in financial shambles. It's been battling an economic downturn, it labors under a Rube Goldberg-ian system of fiscal relationships to the U.S. mainland, and it faces over $70 billion in looming debt repayments — a staggering 89 percent of its personal income. (The average ratio for a U.S. state is 3.4 percent.) The territory may face "a humanitarian crisis as early as this winter," an anonymous White House source told The New York Times.

The Obama administration has worked up a possible deal to avert the crisis. But it would effectively add a new chapter to U.S. bankruptcy law, as well as provide Puerto Rico some fiscal help. So the austerity-obsessed denizens of the House of Representatives would have to pass it, which seems unlikely.

But as with most economic stories in the news, it's important to pause here and return to fundamentals. Get back to the central tree trunk of knowledge, as it were, then rework the problem from there. This may not change our options in the end — the political constraints will remain what they are — but it will at least enable us to see our choices clearly.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The discussion of Puerto Rico has been beset by a weird collective groupthink. The core of the problem gets brushed over, and everyone goes spinning off into tangents. Should Puerto Rico cut its education spending and public investments, so it can pay off the wealthy hedge funds that hold most of its debt? Were the various complicated tax breaks the territory's manufacturers long-enjoyed — the loss of which, along with beginnings of the Great Recession, may have triggered its 2006 downturn — a bad idea? Et cetera, et cetera.

Here is the situation: Puerto Rico has been in an almost-continuous recession for nine bloody years. That means falling income throughout the economy, which means falling tax revenue even if tax rates stay constant. That in turn means a budget crunch. Our politicians talk about government budgets as if they exist in a vacuum, determined solely by the prudence of politicians. But this is poppycock. Government budgets are second-order functions of the economies they sit atop of. If the economy falls, the budget will be dragged down with it, no matter how virtuous the policymakers.

So Puerto Rico's economy must be fixed to fix the other problems. That will require big deficit spending for a while: investment in public programs like pensions and education and health; aid to put a floor under everyone's purchasing power; and low taxes to avoid choking off recovery.

Unfortunately, Puerto Rico can only borrow the money to do that if creditors lend it money at reasonable rates — precisely what the financial markets are not willing to do. As it turns out, there's a weird quirk in U.S. tax law that means Puerto Rican bonds are uniquely subsidized in the U.S. tax code. The territory used this to gorge on debt before the 2006 downturn, to no noticeable benefit: It didn't invest in new permanent infrastructure like public transit, or new industries like tourism. You can argue this was strategically unwise; if you're dependent on lenders when you go into a crisis, you should stay in their good graces when you're not in crisis.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But the thing is, if Puerto Rico controlled its own currency, none of this would matter. It could just stiff its creditors, then have its central bank operate as its "creditor of last resort" by printing new money and buying up whatever new debt it needed to issue, keeping interest rates down. Then, once its economy was back on its feet, Puerto Rico could raise its taxes and pay its debt service obligations to bleed off any possible rise in inflation.

So Puerto Rico is yet another lesson it why it's a terrible idea for any government to control the fiscal policy of a given society without also controlling the monetary policy for it.

Which brings us to the reality of the problem. Puerto Rico can't borrow and it can't print money. If it hikes its taxes or cuts its spending to balance its budget and pay off its creditors, the territory will defeat itself by driving its economy even deeper into the ditch. There is quite literally nothing Puerto Rico can do, under its own power, to fix its situation.

So we need an outside power — the U.S. obviously being the best candidate — to step in and use its ability to borrow to unilaterally subsidize Puerto Rico's budget without condition. That's where the political constraints come in, since the GOP-dominated legislature would never agree to such a thing.

The Obama administration's bankruptcy gambit is essentially an attempt to thread the needle between all these competing forces: allow Puerto Rico to stiff its creditors to a limited extent, restructure its budgetary balance, and use a reform of its Medicaid system and other public investments to provide the country with some fiscal aid. The administration is gambling that, faced with the potential of a big shock to financial markets, Republicans will violate their austerity principles a little bit, if not a lot.

Finally, there is one other interesting possibility: Just make Puerto Rico a full-fledged state. Individual U.S. states don't control their currency either, but they don't fall into crises like this because federal spending programs constantly reshuffle money to the poorest states, propping them up. While Puerto Rico does enjoy aid from federal programs like Medicaid and Social Security, they're capped and attenuated compared to the mainland. The territory is also dirt poor — its GDP per capita is currently less than $20,000, which is a good $10,000 below the poorest state. So simply bringing Puerto Rico fully into the fold would trigger an immediate flood of new federal spending, with no need for offsetting tax hikes, as Puerto Ricans qualified for various mandatory aid programs.

At any rate, them's the options.

The bitter irony is that the best solutions are impossible, and the merely good ones are extremely unlikely. But in terms of what caused the crisis, any failures on Puerto Rico's part are several notches down the list. It's mainly the fault of our shared fiscal policy, which is foolishly designed. And it's the fault of our leaders, who are gripped by a combination of ideological mania and basic macroeconomic ignorance.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

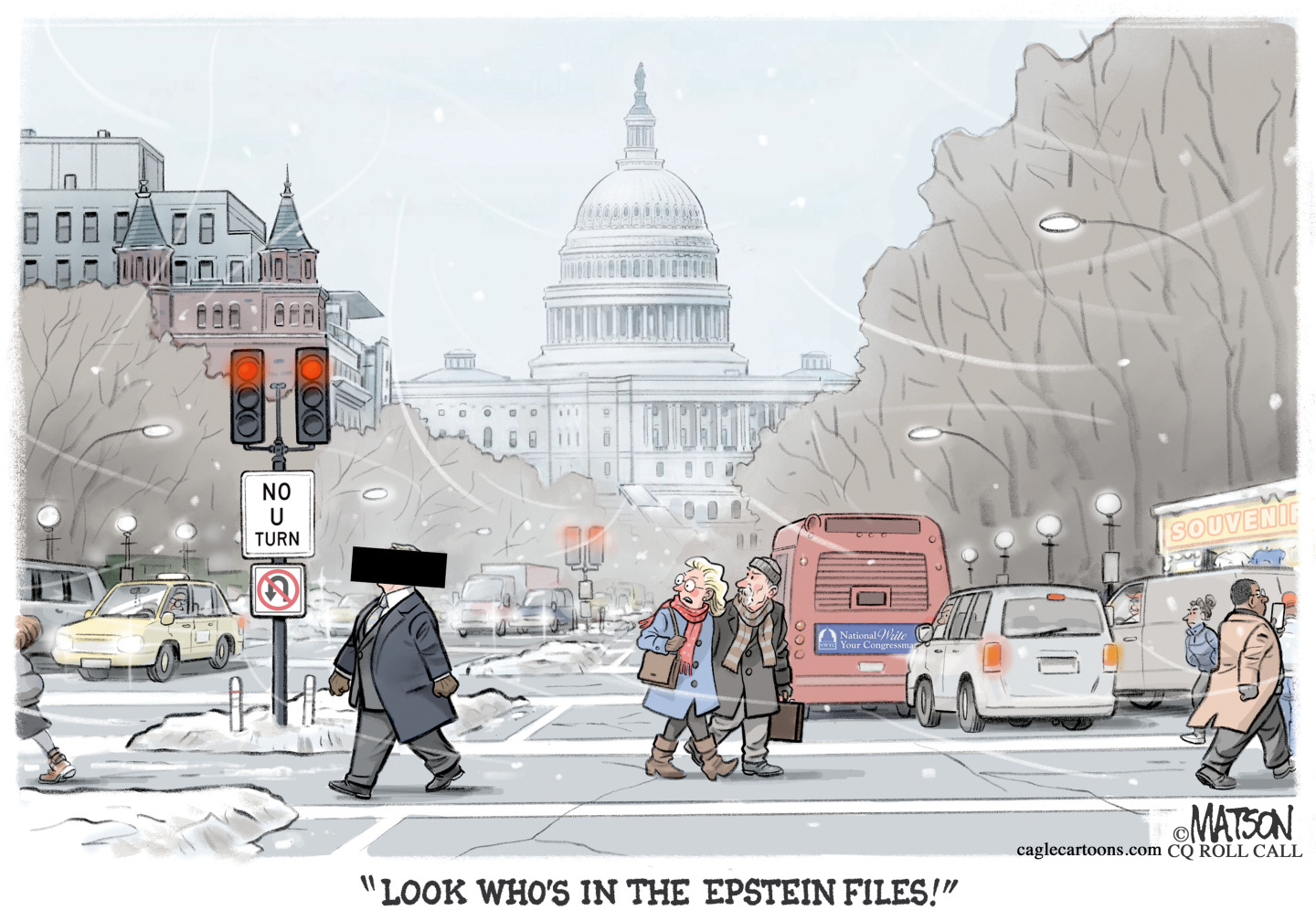

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactions

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactionsCartoons Artists take on hidden identities, a censored presidential seal, and more

-

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonadeTODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns