This amazing 90-year-old WWII veteran just got his high school diploma

Bravo, Mr. Rowlands

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There was just one time during all of World War II when Francis "Sonny" Rowlands was scared.

Now 90, the WWII veteran remembers it clearly. It felt like a "suicide mission." The USS Dunlap was working out of Iwo Jima, and had to go into Hahajima island. "It was like a light bulb," he said. "We went down a real narrow body of water, into a big area where they had a lot of their ships. We were supposed to go down and make a circle and then go into this narrow deal, where they could shoot at you from either side with a rifle. We were supposed to take them by surprise to beat that."

The plan was to go in, drop the torpedoes, then "get the hell out of there." The Dunlap was the flagship, and the destroyer behind it caught a mine, which went up into the magazine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"There were three guys down there, pushing ammunition, and they couldn't get out," Rowlands said. "They kept talking on the phone, until the water finally got up and they drowned. You couldn't open it up and let them out; it makes an air pocket and it really would have come in. That always stayed in my mind. They aborted the trip on account of that, and we all pulled out and went back to Iwo Jima."

Rowlands was just 18 when he joined the Navy. Most times, "we were too young to get scared," he said. Rowlands was at an age where he felt invincible, and figured he had a plum assignment aboard the Dunlap: "I happened to be lucky enough to get on a destroyer, and to see three-fourths of the world."

Joining the Navy and serving in the Pacific was the last thing a young Rowlands expected. Born and raised in Ontario, California, he didn't find high school all that interesting, and his father issued an ultimatum: "I was either gonna have to work, or give that seat to somebody who wanted to learn." But before he could decide whether to stay in school, Rowlands was drafted, and in January 1943, he started his stint on the Dunlap, sailing out of San Diego with 270 other crew members.

There were two special guests on board: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his dog, Fala. "We took him up to Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands, for a day of fishing," Rowlands said. While in San Diego, a bathtub was installed on the ship for the president, and a ramp was built so he could go to his room on an upper deck. The sailors were allowed to talk to FDR whenever they wanted. "He was a common person," Rowlands said. "It wasn't a big thing."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Dunlap's home port was Pearl Harbor; it was at sea on Dec. 7, 1941, and arrived the day after the attacks to patrol the islands. In 1943, Pearl Harbor was one of the first stops Rowlands made on the Dunlap, and he said he was glad to be there, "for my country." From there, they went out to the heart of the Pacific Theater, working with the Third Fleet from the Marshall Islands down to Iwo Jima.

"I remember at the Marshall Islands, the battleships were out on the horizon and they were shooting and we heard the shells go right over us, going to the island," Rowlands said. Next, the Dunlap joined the English fleet and operated out of Ceylon, protecting the aircraft carrier Saratoga. Rowlands was a Baker, Third Class, and had to make 96 loaves of bread every night, as well as assorted pastries, pies, and donuts; he was also a projectile gunner.

"We had pretty good teamwork," he said. "Everybody got along pretty well for the amount of us there were. You'd just wait for the next time you hit port so you could knock the hell out of a bunch of 'em from another ship."

While in the service, Rowlands started writing to a woman named Fran, whose parents knew his parents. She was also from Ontario, and after the war was over and Rowlands readjusted to civilian life, the two married in 1946. Rowlands started working at his uncle's heavy equipment supplier in Ontario, eventually becoming the owner, and he and his wife had two children.

Over the years, Rowlands rarely thought about not having obtained his high school diploma. But he also knew that times have changed, and now "you can't stop at high school because you need more education if you're going to be anything at all in this world. Back when I was going to high school, there was still a future out there you could make if you wanted to get out and work for it. Nowadays I don't think there's a starting point."

And as Rowlands proves, a diploma is more than just a piece of paper.

Rowlands was reading the local newspaper when he spotted an ad for Operation Recognition Veterans Diploma Project, a program offered by the San Bernardino County Department of Veterans Affairs and Superintendent of Schools. The goal of the project is to award diplomas to men and women living in the county whose high school education was interrupted due to serving in the military or internment in a Japanese relocation camp.

"I got my daughter and said, 'Check this out,'" Rowlands said. "I never really thought I'd ever get one, and I thought I'd go for it."

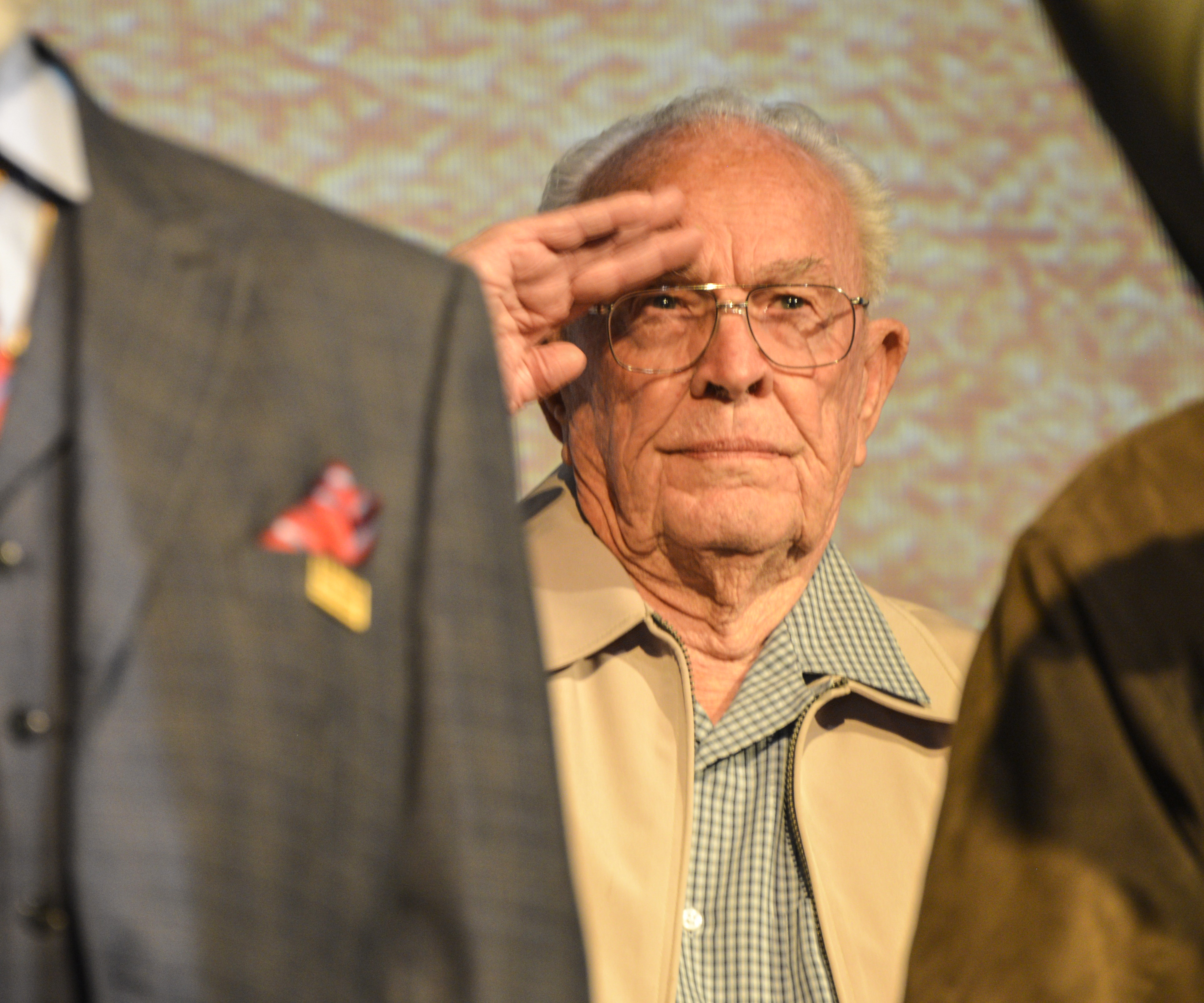

On Nov. 4, along with other veterans who served in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, Rowlands attended a special ceremony and received his diploma, more than 70 years after he last stepped into a classroom. "It's a satisfaction," he said. "I think it's really showing an appreciation to veterans when they come back. It's a small thing, but it's pretty important to know that somebody cares."

Rowlands will keep his diploma with his discharge papers, but first plans to show it to his two great-grandchildren, both students in college.

"I always talked my kids into at least finishing high school, and they did. And I sat back and could never say I had a high school education," he said. "Now, I'm pretty complete."

Catherine Garcia has worked as a senior writer at The Week since 2014. Her writing and reporting have appeared in Entertainment Weekly, The New York Times, Wirecutter, NBC News and "The Book of Jezebel," among others. She's a graduate of the University of Redlands and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.