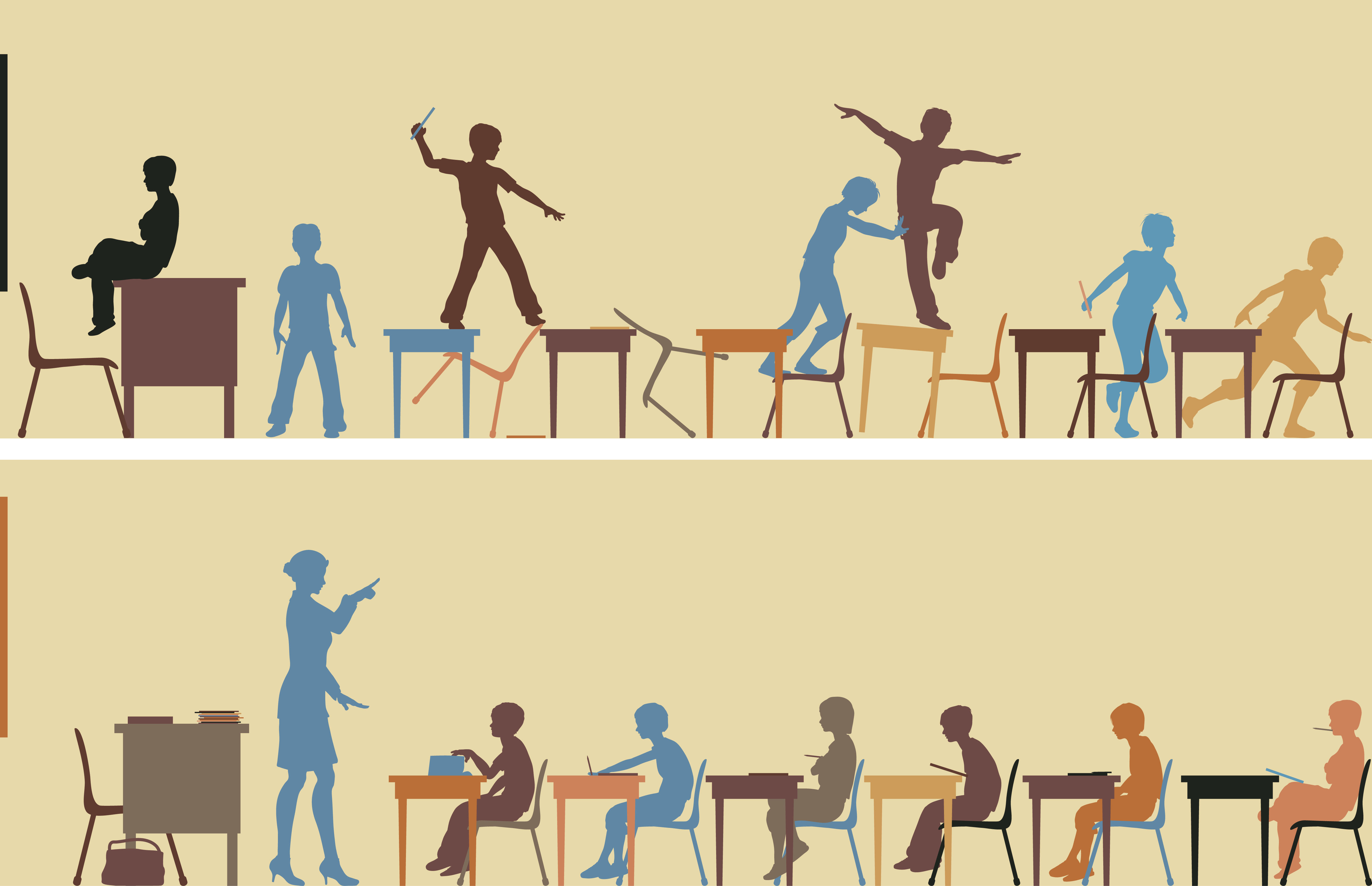

Ban school suspensions!

Not only does this archaic form of school punishment not work, it's bad for our kids

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One day this spring, my 6-year-old came home from school with deep scratches on his arm. After several meandering stories involving fictional characters, he divulged that a friend had used his fingernails to get attention. I suggested my son ask his friend not to do this again. Matter closed.

In another family, at another school district, the story might have ended very differently for one or both boys. They could have been suspended for causing minor injury. But in July, the New York City Department of Education told its elementary school principals that — barring outstanding circumstances — they could no longer suspend students in kindergarten through second grade. Instead, they would have to use other methods to help young children learn to play nice.

Nearly three million American schoolchildren are suspended — or made to stay home due to misbehavior — in any given school year. About 20 percent of the 2013 graduating class had been suspended in high school for offenses ranging from dress code violations to fighting or drug use. The most serious offenses — like guns in school — involve police and expulsions and are regulated by federal law. But more often, suspensions target smaller and often more subjective crimes like "defiance," physical contact, or bad language.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

New York City is one of a handful of places where educators are starting to rethink the usefulness of this archaic practice. California, Connecticut, and Oregon already passed similar restrictions on suspensions, while bills are pending in New York state and New Jersey. Other states and districts have asked schools to try a host of alternative options called "restorative practices" or "positive behavioral interventions and supports."

Why? Well, because suspensions don't work.

That's not just my opinion. The American Psychological Association says suspensions for students who "defy" a teacher don't help the suspended student and don't provide greater order or safety for those left behind, and there's academic research to back that up. Yes, there should be a consequence for actions that hurt others. But out-of-school suspension doesn't prevent bad choices, and worse, it leads to lost learning for those who may need it most.

Suspension is also a lazy option for correcting behavioral problems. As a fellow parent told me once, removing a kid from school "is just kicking the can down the road. It's not helping the child, the parent, educators. It's not even a short-term solution. It's just nothing." Instead of helping a student learn to do the right thing, a suspension often ignites a cascade of future failures, including more suspensions and entry into the juvenile justice system.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Not only are suspensions counter-productive, they are discriminatory in their application: Black students are suspended at nearly four times the rate as white students, even in preschool. The higher suspension rates for black students (particularly black boys) has little to do with them committing more offenses. Even after researchers take into account other variables, such as poverty, black students in poverty are still suspended more than white students in poverty. Neither are black students committing serious infractions at higher rates; it's the discretionary offenses where racial differences most appear. This is bad for educational outlooks: Suspension in high school increases the rate of dropping out by at least 12 percent. But it's also bad for states' bottom lines: A recent analysis by the UCLA Civil Rights Project estimates that reducing suspensions could save states billions of dollars in the long term.

The good news is that some schools, districts, and states are recognizing this and are holding back on sending kids home for acting out. And it's working. In June, the Office of Civil Rights noted a marked decline in suspensions.

The practice of sending kids home for bad behavior may ultimately go the way of another old schoolroom disciplinary technique: corporal punishment. The controversial practice of reprimanding a child through physical violence is still accepted in 19 (predominantly Southern) states, but anathema in others. Interestingly, the states moving to ditch school suspensions are some of the same ones that first banned corporal punishment. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the movement corresponds with blue and red states on political maps.

So if suspension doesn't work, what's the alternative? Talking about conflicts and having offenders make meaningful restitution works around the country, where it is put into place thoroughly and thoughtfully. This has worked in Denver, where public schools dropped suspensions by two-thirds and cut the discipline gap between African-American and white students by a third after implementing a restorative justice program. Broward County, Florida banned suspensions for non-violent acts in 2013 in favor of counseling and saw incidents drop. After 200,000 fewer kids lost school time when these discretionary suspensions were discouraged in California, researchers found that fewer suspensions lined up with higher test scores.

Back in New York City, more than $50 million has been provided for training in positive behavioral interventions and support programs or restorative practices, which involve a lot more than talking about your feelings. These programs emphasize noticing trends in student stress and helping kids before they fly off the handle. They include using direct and affirmative language ("flush toilets after use" versus "don't leave a mess") and coming up with solutions to conflicts with everyone involved.

Some teachers complain that they haven't been trained yet in these practices, so suspension bans are premature. But as Cassie Swerner, senior vice president at The Schott Foundation, points out, "The bans have to happen immediately because of the cost to young people, not only in their immediate lives but in their futures — you can't get that year back."

Carly Berwick contributes to TheAtlantic.com and Next City and has been an editor at The Week and ARTnews. She has written about culture and cities for many publications including Bloomberg News, The New York Times, Art in America, Conde Nast Traveler, and New York magazine. She lives and teaches in New Jersey.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day