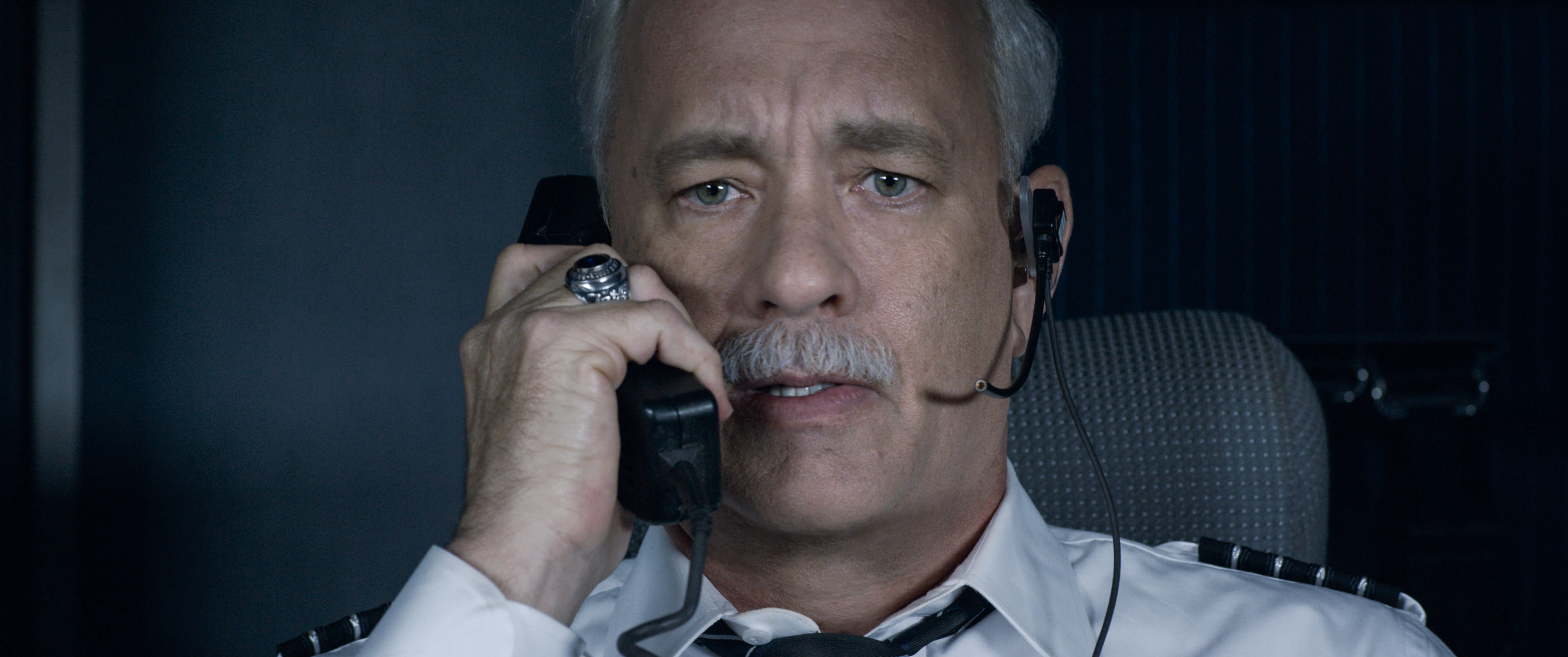

An ode to Tom Hanks' upper lip

It curls, it smirks, it has a sense of humor. And when it's obscured, as in Sully, something wonderful is lost.

Sully is the kind of movie you ought to see in IMAX if you're going to see it at all. The new Clint Eastwood film about Chesley Sullenberger, the pilot who successfully landed United Flight 1549 in the Hudson River after a bird strike in 2009, has grand cinematography: When the airplane lands in the river, you'll feel it. You'll shiver as the passengers stand on the airplane's wings in the dead of winter, baffled and scared and freezing wet. IMAX is the medium for a spectacle of this scale.

Unfortunately, the cinematic catharsis of 155 people surviving a crash gets nearly neutralized by the outsize atrocity atop Tom Hanks' lip.

I say this with love, and with no particular hatred of moustaches (the one Aaron Eckhart grew for the film, for instance, works beautifully). Hanks is a gifted actor and he remains one of the best things about this movie despite the white thing on his face; if Sully is a competent three-star film with five-star ambitions, Hanks is responsible for two of those stars. But something is obscured in Sully. Something is missing, and its absence becomes that much more palpable in IMAX. I'm talking, of course, about Tom Hanks' philtrum. His cupid's bow. His brilliant vermilion border. His Oscar-winning labial tubercle.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

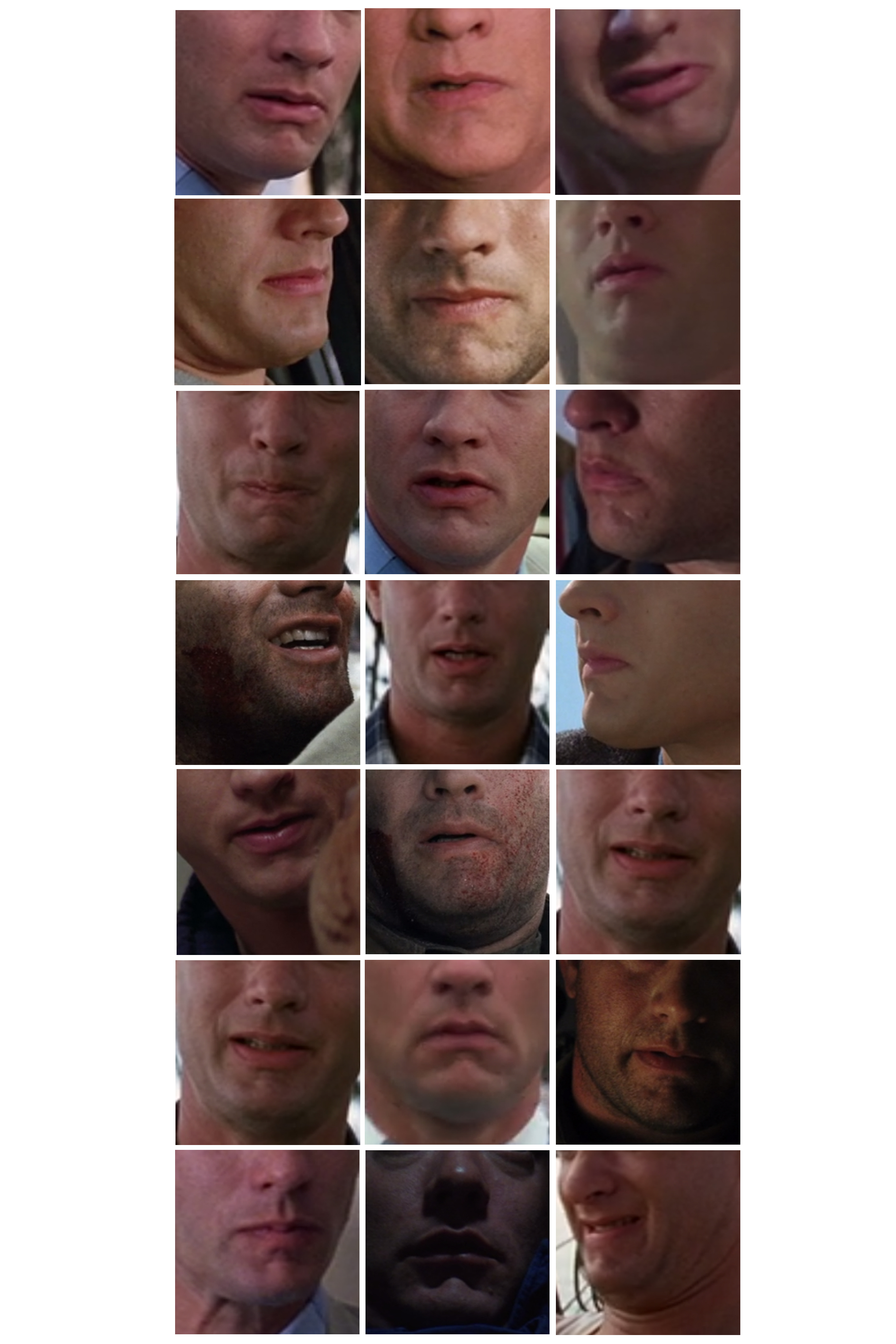

I'd never realized how much work Hanks does with his excellent upper lip before this film deprived him of the use of it. He's had moustaches before, of course, but never like this. In Saving Mr. Banks it was a trimmed-down version that still allowed the contours to peek through. Sully shows no such restraint. The film buries one of American cinema's greatest assets behind a scrubby, too-long set of whiskers. I wouldn't have thought hiding the philtrum would matter; it took losing it to realize what we had. What's a lip, after all?

But when I think of Hanks at his most idiosyncratically expressive — doing Godfather impressions in You've Got Mail, staring down the dog in Turner and Hooch, or battling a coconut in Castaway (skip to 1:30), what comes to mind is, inevitably, his mouth. It's a sly character actor in a face we love for its bland and handsome familiarity. Treacherous and adaptive, it moves like crazy when a character's trying to persuade: Watch it as Joe Fox tells Kathleen Kelly how much he likes her, observe how it arcs up and flattens out and turns curly in supplication.

It's so manipulative it's practically sentient. Forrest Gump's earnestness, in contrast, is 80 percent a function of the relaxed, un-self-conscious slackness of that upper lip as he tells his story. (I have struggled in vain to screenshot examples of these things for you, but the magic of Hanks' upper lip is a function of how fleetly it moves between states and feelings. It can only be observed in action.)

It even has a sense of humor, the lip does: Hanks' dancing in the classic radio scene from Joe vs. the Volcano is comedy at its broadest, but his upper lip is having a whole quiet joke with itself.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And sometimes that upper lip gets mean: Paul Ekman — the expert on facial expressions — says the recipe for contempt is lifting the upper lip on only one side. There it is, right there in the middle of the nicest man in film's otherwise kind and straightforward face, and it puts Meg Ryan badly out of countenance.

If that lip of Hanks' smuggles a mischievous sensibility into a whitebread exterior, what happens without it?

Well, maybe you get a simple, bland, conventional hero.

It didn't look like Sully was heading that way at first. The first half of the script seemed like more than a character study or a procedural: It was dedicated to exploring the psychology of heroism from the point of view of the hero who feels himself to be no such thing. The movie was thinking hard about scripts, about roles, about doubt. Chesley Sullenberger is the perfect lens through which to review our contemporary obsession with antiheroes. He's as close as we're likely to get to an American hero; decent, dutiful, self-deprecating, Sully was allergic to accolades, uncomfortable with fame, and unwilling to accept the narrative shortcuts through which a harrowing experience got reduced and repackaged into "The Miracle on the Hudson." In the film, he's being investigated, and he takes the possibility that he erred seriously: Was his judgment at fault? Did he endanger people because of his age? These unknowable things rankle. How can he live with the uncertainty while everyone around him claps him on the back?

Unfortunately, the script doesn't live up to its early promise. It handwaves doubt away: Nothing is unknowable! Eastwood and screenwriter Todd Komarnicki didn't ultimately see this as a story about PTSD and how living through something alienates you from the way the event is told. Nor did they see it as a story about doubt or uncertainty. Things have answers, and they repeat more than they progress: Sully is repeatedly called a hero by some people, repeatedly asked if he's a fraud by others, and repeatedly trapped in oddly robotic non-conversations with his wife (Laura Linney), who does what she can with lines like "I'm sorry if I'm adding to your stress" and "Please tell me this is almost over." And Sully's doubt, which began as an unanswerable existential problem laced with the ambient horror of 9/11, resolves into a neat and purely procedural one. There are definite, findable truths here, and the story of American heroism concludes intact.

You may feel, as I did, that something major went missing in this tale of a man who shouldered massive responsibility. I thought back to Hanks' work as Captain John Miller in Saving Private Ryan. There's a scene where he talks about how he deals with the impossible choices he makes every day: "You see when you end up killing one of your men," he says, "you tell yourself it happened so that you could save the lives of two, or three, or 10 others. Maybe a hundred others. Do you know how many men I've lost under my command?"

He's lost 94.

But that means I've saved the lives of 10 times that many, doesn't it? Maybe even 20, right? Twenty times as many. And that's how simple it is. That's how you, that's how you rationalize making the choice between the mission and the men.

The difficult choices in Sully have all been made. The long aftermath of Flight 1549 fails to raise the kinds of questions that would have given Hanks' upper lip anything interesting to do. Instead he wanders through the movie, a stunned, nearly anonymous figure pelted with spurts of fame, and endures.

I hadn't thought much about the anatomical implications of keeping a "stiff upper lip" until I saw this film. The expression never made much sense to me: When people cry, it's the lower lip that trembles. It's the chin that crumples and shakes. What do upper lips have to do with it? A ton, it turns out. The upper lip may not be where grief lives, but it somehow contains a character's perspective, his conflicts and contradictions and even his comedy. Sully is about a man who keeps a stiff upper lip in every sense of the word; Hanks' unusually mobile mouth is out of commission here, and the result is a confusing lack of tension. For a Hanks performance, it's admirably restrained, but without much behind it. It feels uncharacteristically empty, curiously flat.

That's not exactly a criticism of Hanks' performance (though I watched some footage of the real Sully to gauge to what extent he was mimicking him — the real Sullenberger seems far more expressive). It is a gentle critique, however, of how little philosophical space Sully's doubts are granted. Of how little use the film made of Hanks' capacity to spike his character's apparent simplicity with a multi-faceted inwardness. Of how much better this film could have been if it had allowed its hero (and itself) some negative capability. Of how little it let him aim that cupid's bow.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

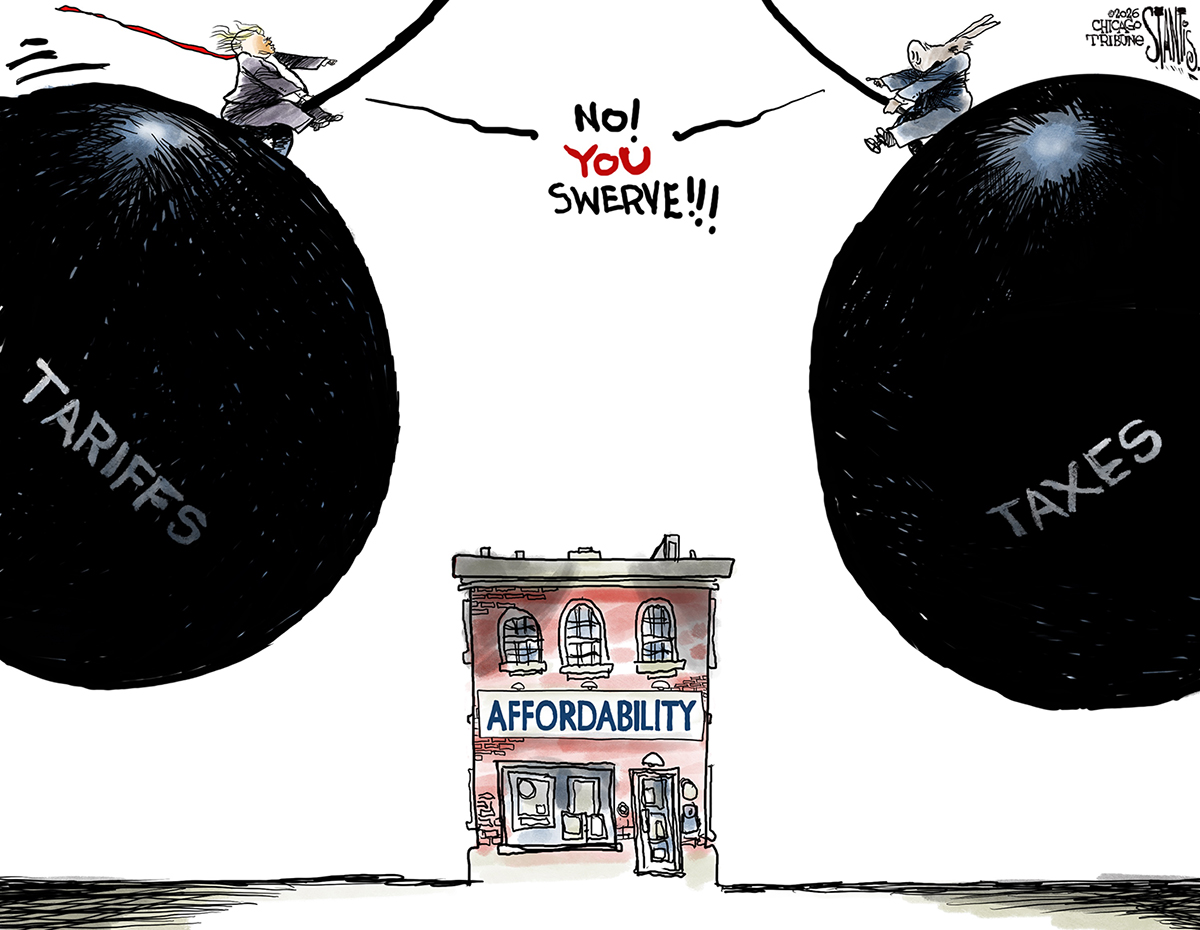

Political cartoons for January 18

Political cartoons for January 18Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include cost of living, endless supply of greed, and more

-

Exploring ancient forests on three continents

Exploring ancient forests on three continentsThe Week Recommends Reconnecting with historic nature across the world

-

How oil tankers have been weaponised

How oil tankers have been weaponisedThe Explainer The seizure of a Russian tanker in the Atlantic last week has drawn attention to the country’s clandestine shipping network