How tiny can nanowires get?

Really, really, really, really tiny

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When it comes to microchips, bigger isn't better. Quite the opposite, in fact: The smaller the chip — and the tinier the components it fits — the more computing power can be packed into one place. But as researchers race to find innovative new ways to make smaller chips, they're running up against a wall: The teensier the chip, the slower and more expensive it is to make.

The culprit is the infinitesimal wires that create circuits on the chips. The tiny wires control the flow of electrical signals and power across chips, and they can be found inside everything from your phone to your hard drive to your microchipped pet.

The more wires, the faster and more powerful a device — but so far, the smallest ones sold commercially limit the amount of power a chip can deliver. The tiniest chips on the market today have wires that are just 22 nanometers thick (about 4,000 of them could fit across the width of a single human hair). But for manufacturers, that's much too large.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As is, these tiny wires are produced using complex fabrication processes that rely on generating light wavelengths that cost a lot and are complicated to produce. Thankfully, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Chicago, and Argonne National Laboratory may have a solution to create smaller wires for less money.

The team describes its discovery in the journal Nature Nanotechnology: "The processors inside your smartphone are more powerful than the computer that took the Apollo mission to the moon," says Priya Moni, a graduate student at MIT who co-wrote the paper. But though the technology is complex, she says, the fabrication process doesn't have to be.

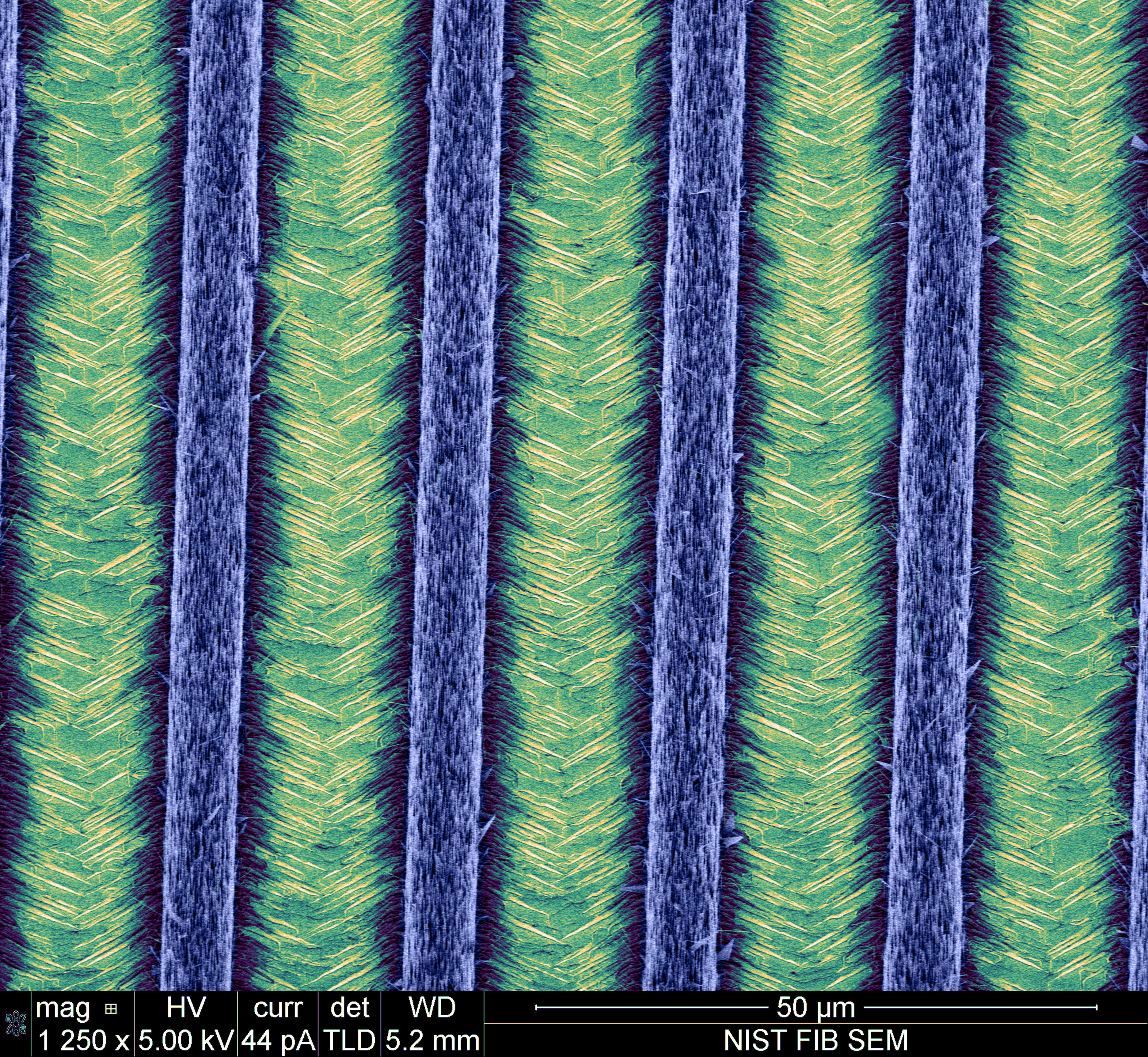

Moni and her colleagues borrowed from existing, but unrelated, fabrication processes to make even smaller wires a possibility. First, they use an electron beam to create a pattern on a tiny structure that's destined for life as a microchip. Then, they create tiny lines with a super-strong substance called a block copolymer. It gets its strength from molecules that sort themselves into wee chains and stick tightly together, forming more patterns on the chip. The third step is to make a top coat of polymer that forces the materials below into tiny vertical layers — turning them into wires that are much smaller than the ones they'd be able to create with any one of the old techniques.

The super-small lines — less than 10 nanometers in width, or a mere 20 atoms wide — do more than save space. Do Han Kim, who co-authored the paper, says that the smaller the wires, the less power is lost during computing. As a result, batteries last longer and devices are more energy-efficient.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"We were able to create very targeted chemistry," says Moni. And since the semiconductor industry is evolving so quickly, she notes, it's important to stay ahead of the curve. "They're always looking for solutions to problems that are 10, 20 years in the future," she says.

Now that the team has developed a better method for creating wires, they'll work to improve the process. Within a decade, you could find them inside your hard drive — ensuring a big future for ever-more-minute microprocessors.

Erin Blakemore is a journalist from Boulder, Colorado. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Time, Smithsonian.com, mental_floss, Popular Science and more.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy