How to revolutionize the tax code with only 'find and replace'

The case for changing every tax deduction into a tax credit

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The tax plan released by the Trump White House last week was blasted for being too simple: a one-page summary of campaign pledges and bullet points. But I think they could have gone simpler. Because if you really wanted to revolutionize the tax code, all you'd need is Microsoft Word's "find and replace" tool.

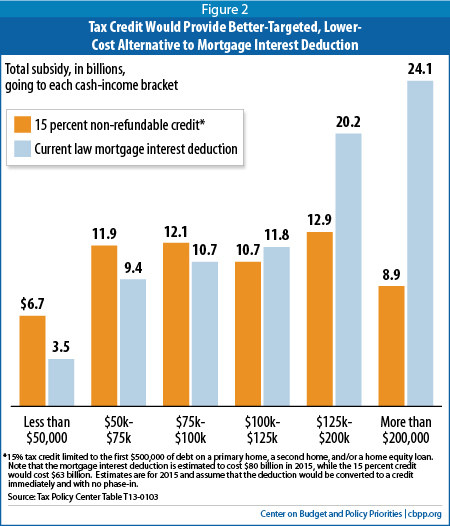

Let's start with the White House's pledge to "eliminate tax breaks that mainly benefit the wealthiest taxpayers." As Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin pointed out Monday, if you cut those loopholes while lowering tax rates, you could provide tax relief to the middle class with "no absolute tax cut for the upper class." But this is harder said than done because tax breaks are usually very popular. For instance, one of the biggest tax breaks is the mortgage interest deduction: a huge giveaway to the wealthy and one of the government's biggest revenue losers. But Mnuchin has already admitted the White House's plan won't touch it. So by the time tax reform is passed — assuming it's ever passed — you can be sure plenty of other tax loopholes will be mysteriously spared the axe.

But there's a better, simpler way. Broadly speaking, tax breaks come in two different flavors — tax deductions and tax credits. And if you want to make the tax code more egalitarian but you think eliminating tax breaks wholesale is too politically difficult, you could just convert tax deductions to tax credits whenever you can.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here's how it works. When you file your taxes, you first have to calculate the amount of income you owe taxes on. Tax deductions reduce that amount. The mortgage interest deduction, for example, removes all the money you paid in interest on your mortgage from the total income you'll pay taxes on. As a result, your final tax bill to the IRS goes down.

But if you're richer, you're probably spending more money on your mortgage, and you're escaping higher tax rates. So the tax deduction helps you more, as an intrinsic consequence of its very design.

Tax credits are different. They come in after you've calculated your final tax bill, and reduce that number directly. So how much any given taxpayer benefits from a tax credit varies a lot less depending on income.

Now, how policymakers set the tax credit's amount can differ. To take the mortgage interest deduction again: If you changed it to a tax credit, you could design it to knock 15 percent of your interest payments off your final tax bill. Or you could just design it to knock a flat $5,000 (or whatever number you want) off everybody's tax liability.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The second variation, with the fixed dollar amount, would be more egalitarian than the first. But even the percentage version of the tax credit distributes its benefits far more evenly than the tax deduction.

There are other deductions in the U.S. tax code that, like the one for mortgage interest, help out the rich the most. If you get your health care through your employer, but pay a portion of the premiums yourself, that money is tax deductible. What you pay in state and local taxes you can deduct from your federal taxes. And so forth.

But we don't have to stop there.

Another aspect of tax credits is something called "refundability." Again, we'll use turning the mortgage interest deduction into a tax credit as an example. Let's say that, under the new system, the mortgage interest tax credit is worth $5,000 to you. But your final tax liability is only $4,500. So the mortgage interest tax credit just wiped away all your tax liability — you owe the IRS nothing. But there's still this extra $500 left over.

If the mortgage interest tax credit was refundable, then you'd get that extra $500 back as a check.

As you can imagine, refundable tax credits specifically are a powerful tool for helping the poor. If you're rich, you're far more likely to use up all of your tax credits and still have tax liability left over. But if you're poor, you're far more likely to run out of liability before you run out of credit. So making tax credits refundable equalizes the benefits still further.

Besides the big ticket deductions for health care and mortgage payments that primarily go to the wealthy, there are also other tax breaks that less well-off Americans often claim: Teachers who buy classroom supplies can deduct those expenses, for example. You can also deduct the expenses of moving for a new job, the money you pay in student loan interest, the money you pay for tuition, etc. But once you've eliminated your tax liability, these tax breaks can't help you any more. If they were transformed into refundable tax credits, they'd do even more to lift up less fortunate Americans.

Now, there will be complications. We'd have to decide when to design the tax credits as a percentage versus a fixed dollar amount (I think we should lean towards the latter as much as possible). The tax credits would also have to be sufficiently generous to really help. We'd also need to resist any impulse to ignore the poorest Americans; right now, for example, there's a child tax credit that actually phases in as your income goes up, which obviously leaves the poorest parents out in the cold.

There would be other issues to consider, too. Going back to mortgage interest: Even if we changed it to a refundable tax credit, what about renters? They tend to be poorer than home owners. So really, we should change the mortgage interest deduction into a universal refundable tax credit for all housing expenses: Same dollar amount of help to renters and homeowners alike.

This change wouldn't be a cure all. But tax reform tends to get sold on big rules of thumb: "Cut tax loopholes and lower tax rates" is one obvious example. "Change every tax deduction you can into a refundable tax credit" could be equally powerful politically. And when it comes to making the benefits of our tax code flatter, fairer, and more universal, it would be hard to find a rule of thumb that would work better.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.