The children haunted by 12 seconds of gunfire

Over the past two decades, more than 135,000 American students have experienced a shooting at their school. In one small town, first-graders remain tormented by what they saw.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Recess had finally started, so Ava Olsen picked up her chocolate cupcake, then headed outside toward the swings. And that's when the 7-year-old saw the gun.

It was black and in the hand of someone the first-graders on the playground would later describe as a thin, towering figure with wispy blond hair and angry eyes. Dressed in dark clothes and a baseball cap, he had just driven up in a Dodge Ram. It was 1:41 on a balmy, blue-sky afternoon in late September of last year, and Ava's class was just emerging from an open door directly in front of him to join the other kids already outside.

Then he pulled the trigger.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"I hate my life," the children heard him scream, in the same moment he added Townville Elementary in Townville, South Carolina, to the long list of American schools redefined by a shooting.

A round struck the shoulder of Ava's teacher, who was standing at the green metal door, before she yanked it shut. Near the cubbies inside, 6-year-old Collin Edwards felt his foot vibrate, then burn, as if he had stepped in a fire. A bullet had blown through the inside of his right ankle and popped out beneath his big toe, punching a hole in the sole of his Velcro-strapped sneaker. As his teachers pulled him away from the windows, Collin recalled later, he spotted a puddle of blood spreading across the gray tile floor in the hallway. Someone else, he realized, had been hurt, too.

Outside, Ava had dropped her cupcake. The Daisy Scout remembered what her mom had said: If something doesn't feel right, run. She sprinted toward the far side of the building, rounding a corner to safety. Nowhere in sight, though, was Jacob Hall, the tiny boy with oversize, thick-lensed glasses Ava had decided to marry when they grew up. He had been just a few steps behind her at the door, but she never saw him come out. Ava hoped he was okay.

Standing on the wood chips near a yellow tube slide, Siena Kibilko felt stunned. Until that moment, her most serious concern had been which How to Train Your Dragon toy she would get for her upcoming seventh birthday. "Run!" Siena heard a teacher shouting, and she did.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Karson Robinson, one of the biggest kids in class, hadn't waited for instructions. At the initial sound of gunshots, he scrambled over a fence on the opposite side of the playground. He then turned back to the school and found his classmates banging on a door. "Let us in," Siena begged, and the kids were hustled inside.

The gunfire had stopped by then, and in a room on the other side of the school, Collin had discovered the source of all that blood.

Sprawled on the floor was Jacob, the boy Ava adored. At 3½ feet tall, he was the smallest child in first grade — everyone's kid brother. On the green swings at recess, Collin would call him "Little J" because that always made Jacob cackle in a way that made everyone else laugh, too. But now his eyes were closed, and Collin wondered if they would ever open again.

"Look at me," a teacher urged Collin, but the boy couldn't stop staring at his friend.

On a gray wall inside Townville Elementary's front lobby hangs a framed dream catcher, and beneath its blue beads and brown feathers is a Native American phrase: "Let us see each other again."

It was among hundreds of items — letters, ornaments, photos, posters, plush toys — that deluged the school of 290 students after the Sept. 28 attack. But the dream catcher held special meaning. It had been sent to four other schools ravaged by gun violence, and the names of each were listed on the back: Columbine High in Colorado, Red Lake High in Minnesota, Sandy Hook Elementary in Connecticut, Marysville Pilchuck High in Washington state.

In each shooting's wake, the children and adults who die and those who murder them become the focus of intense national attention. Often overlooked, though, are the students who survive the violence but are profoundly changed by it.

Beginning with Columbine 18 years ago, more than 135,000 students attending at least 164 primary or secondary schools have experienced a shooting on campus, according to a Washington Post analysis. That doesn't count dozens of suicides, accidents, and after-school assaults that have also exposed children to gunfire.

"A meaningful number of those kids are going to have significant struggles," said Bruce Perry, a psychiatrist who worked with families from Columbine and Sandy Hook. "It's stunning how one event can have this echo that will impact so many more individuals than people realized."

Every child reacts differently to violence at school, therapists have found. Some students, either immediately or later, suffer post-traumatic stress similar to combat veterans returning from war. Many grapple with recurring nightmares, are crippled by everyday noises, struggle to focus in classes, and fear that the shooter will come after them again.

Because of the lasting damage, Townville's teachers, administrators, first responders, counselors, pastors, and parents and their children agreed to speak about what the community of 4,000 has endured over the past nine months.

They'd always felt safe in this swath of countryside, which claims a single stoplight but at least six churches. Overwhelmingly white, it is home to families that have farmed for decades, retirees with lake houses, college-educated professionals, and hundreds of people in mobile homes living from one paycheck to the next.

What connects them is a beloved two-story, red-brick school where generations of children have gathered to learn and play and grow up together.

The gunman paced the sidewalk, a cellphone in his hand. Moments earlier, as he had shifted his aim from the green metal door to the playground, his .40-caliber pistol jammed, ending his rampage 12 seconds after it began. Now Principal Denise Fredericks and some of her staff congregated at the end of a second-floor hallway to keep track of him until help arrived.

Then he looked up. "That's Jesse Osborne," a teacher gasped. He was 14 years old.

Jesse had attended Townville — walked its halls and romped on its playground — through fifth grade, before he transferred and was later homeschooled. Not once, Fredericks said, had his behavior prompted concern. He was quiet, earned good grades, and almost never got into trouble. He played catcher in the recreation league. He got invited to birthday parties.

Jesse had called his grandmother, Patsy Osborne, just minutes before he'd driven to the school that afternoon. He was screaming, she said. She couldn't understand him.

Patsy and her husband, Thomas, sped to his house, where they discovered their son — Jesse's father — slumped on a couch, eyes still open. He'd been shot to death.

Thomas later pulled up to the school just moments after Jesse had been subdued by an armed volunteer firefighter, arriving in time to see his handcuffed grandson loaded into the back of a patrol car.

Inside the school, 300 children and teachers cowered in locked classrooms, bathrooms, and storage closets. Siena remembered someone covering up windows with paper. Karson remembered playing with markers and magnets. Ava remembered a teacher reading a story about sunflowers. They all remembered the sound of weeping.

A week later, on a Wednesday morning in October, Jacob lay inside a miniature gray casket topped with yellow chrysanthemums and a Ninja Turtles figurine. He was dressed in a Batman costume. His family had asked that people attending the service dress like superheroes because of the boy's infatuation with them. Ava wore a Ninja Turtles top with a purple cape. Siena and Collin both dressed as Captain America.

From their seats, the children watched as Jacob's mom staggered to his casket, then collapsed on the floor. They stared as his body was wheeled up the center aisle at the end of the memorial. Then, just hours after their friend's funeral, they returned for the first time to the place he'd been shot.

"What if he gets out?" Siena asked her parents in the days after the shooting. Then she never stopped asking. They explained that Jesse Osborne was in jail, that she was safe. But still, Siena obsessed over him coming for her again. Next to a sign beside her top bunk that read "Night, night, Sweet Pea — sweet dreams," she relived the shooting in her nightmares.

Each morning included a negotiation with her parents. "I don't want to go to school today," she would say. "I don't feel good."

At drop-off, she would search the parking lot for the cruiser of the police officer assigned to Townville Elementary after the shooting. She needed to know he was there.

One day, Siena announced to her mother that she couldn't go to summer camp anymore: "They don't have a police officer."

Like many of her classmates, she was petrified by loud, unexpected sounds. Once, outside a Publix supermarket, a car backfired, and she dropped to the ground before dashing inside. Another time, after a balloon popped at a school dance, the entire gymnasium went silent as Principal Fredericks rushed to turn the lights on. She later banned balloons at the spring festival. "Noises are different now," she said.

A month after the shooting, Karson was beginning to sleep and eat normally again, but a sense of guilt still haunted him. "Maybe I should have waited on Jacob," he told his mother. "He could have jumped over the fence with me."

She insisted he couldn't have saved Jacob's life, but Karson wouldn't be persuaded. He stood half a foot taller than his friend, whom he'd known since they were toddlers. Big kids were supposed to help little ones.

He didn't like it when people mentioned Jacob's name. For Valentine's Day, Karson wrote a card in his memory: "I loved him but he diyd but he is stil a life in my hart."

In the corner of his room, behind a bunk bed covered in Paw Patrol sheets, Collin rummaged through a plastic toy bin. His medical boot had come off months earlier, and the bullet wound had healed, leaving a dark, nickel-size splotch on his ankle. He could run again, though sometimes he had to take breaks because of the pain.

Collin found what he was searching for and held up a plastic pistol. "His gun looked like that," he said, his tone matter-of-fact.

Of all the children who survived that day, Collin seemed the most vulnerable to psychological damage in the eyes of many Townville parents and teachers. Before learning to tie his shoes, he'd been shot and seen his friend covered in blood. But he didn't have nightmares, and he didn't think much about Jesse. At school, as long as one of his stuffed animals was within reach, he felt fine.

His father, a 200-pound construction worker, broke down about what had happened more often than Collin did. It wasn't that the boy didn't care, because he did, especially for Jacob's 4-year-old sister, Zoey, whom he'd often hug when he saw her.

But Collin, now 7, can discuss that day with clarity and composure. Researchers who have studied kids for years still aren't certain why they react to trauma in such different ways.

Perhaps no one understands that better than Nelba Marquez-Greene, whose son survived the Sandy Hook massacre but whose daughter did not. "That's a factor you can't predict — how your child is going to deal with it," said Marquez-Greene, a family therapist for the past 13 years. She warned, however, that parents can't assume their kids have escaped the aftereffects, which sometimes don't surface for years.

"We still have this tendency to want to say, 'Okay, it's done. He's good. She's good,'" Marquez-Greene said. "That's not where the story ends."

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

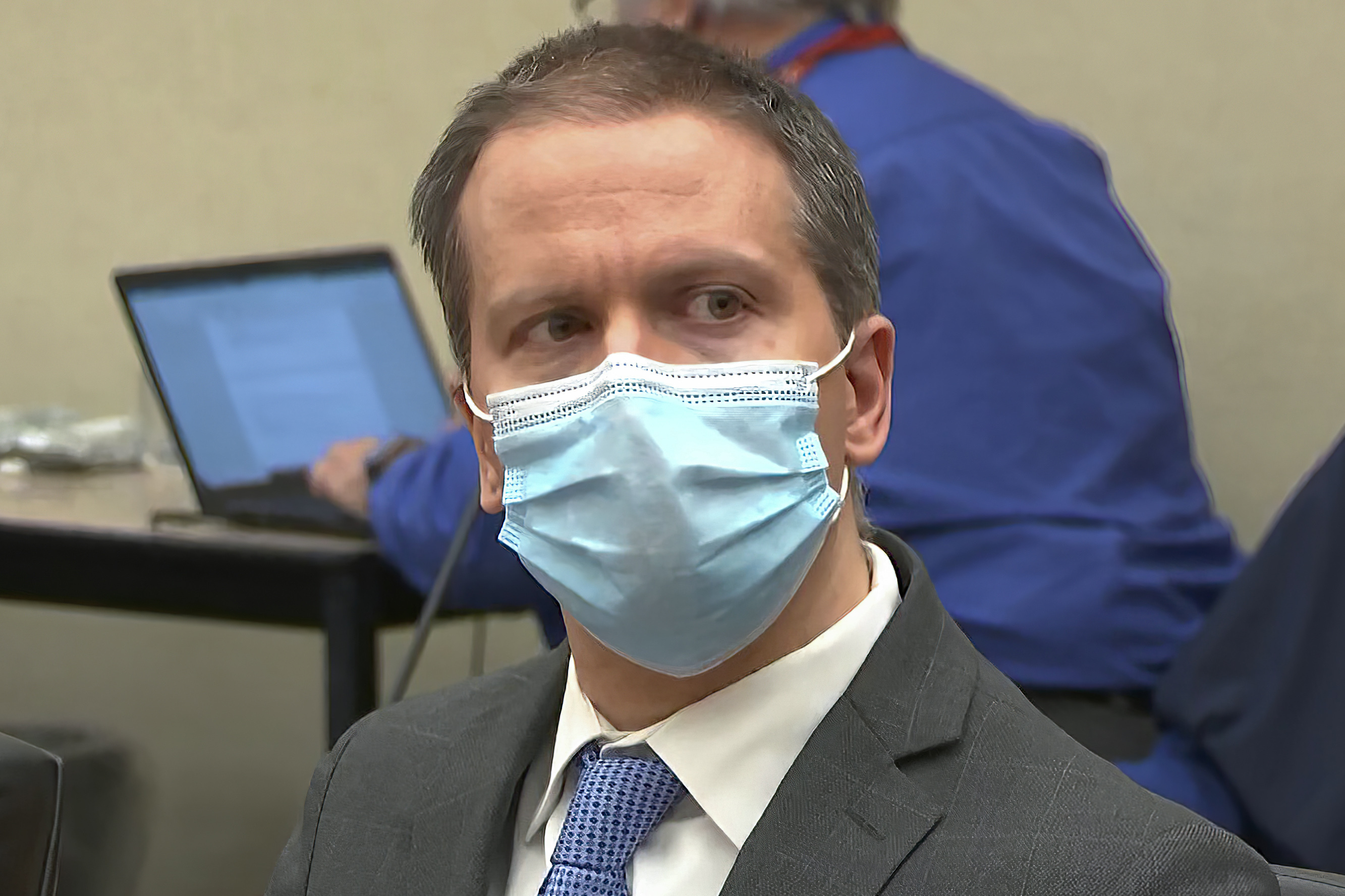

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read