The rapture of nostalgia

Why nostalgia is at once an acknowledgment of death and a quiet reassurance that it is not final

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When he was a child a family friend asked the future historian and biblical translator Mgr. Ronald Knox what his favorite thing to do was. "I lie awake and think about the past," the 4-year-old replied. I used to be reminded frequently of young Knox's comments by a perfectly unmusical "song" I used to hear in cabs that went "Wish we could go back / To the good old days."

These are, however frightfully expressed, sentiments to which, as Dr. Johnson once neatly put it, "every bosom returns an echo." Or rather nearly every bosom. The fierce loathing of the past typified by Elon Musk and other grandees of Silicon Valley is an interesting topic beyond the scope of this article. The rest of us are hopelessly enthralled by the past.

The primary form that this enchantment takes is nostalgia, which, more so than despair or even anger seems to me the emotion most fundamental to our age and, as Matthew Continetti wrote recently, "our national mode." Nostalgia is the reason the most popular film of this year will almost certainly be yet another Star Wars sequel, why dozens of books have been published this year on the 50th anniversary of a single overrated Beatles album, why Harry Potter remains a favorite political metaphor in this country, why an entire political party is organized not around principles or even pragmatic considerations of economic interest but around the practice of roleplaying as the Founding Fathers and Ronald Reagan.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I myself am a perfect example of this vassalage to yore. I recently purchased an ancient television-VCR combo unit for the express purpose of playing tapes of the Star Wars trilogy in the form in which I first experienced it. I own crate upon crate of dusty records, some of which — Van Morrison's Astral Weeks, or "Gold Soundz" by Pavement, much of Purcell and Handel and Elgar — can bring me to tears if I'm not careful. I buy my clothing at Brooks Brothers, where nearly everything in the store could have been for sale half a century ago. I spent an hour on a recent morning at the local historical society of the small town in Michigan where I live reading about the WASP grandee-turned pioneer who built my house in 1840 and about his son, a major who died fighting for Grant at Missionary Ridge in 1863. My favorite genres of literature are history — especially ecclesiastical history — and biography. Even when traveling for work I will go to extraordinary lengths to attend Mass in the ancient form of the Roman Rite promulgated by St. Pius V in 1570 rather than the modern form dreamed up in the 1960s in the wake of the Second Vatican Council.

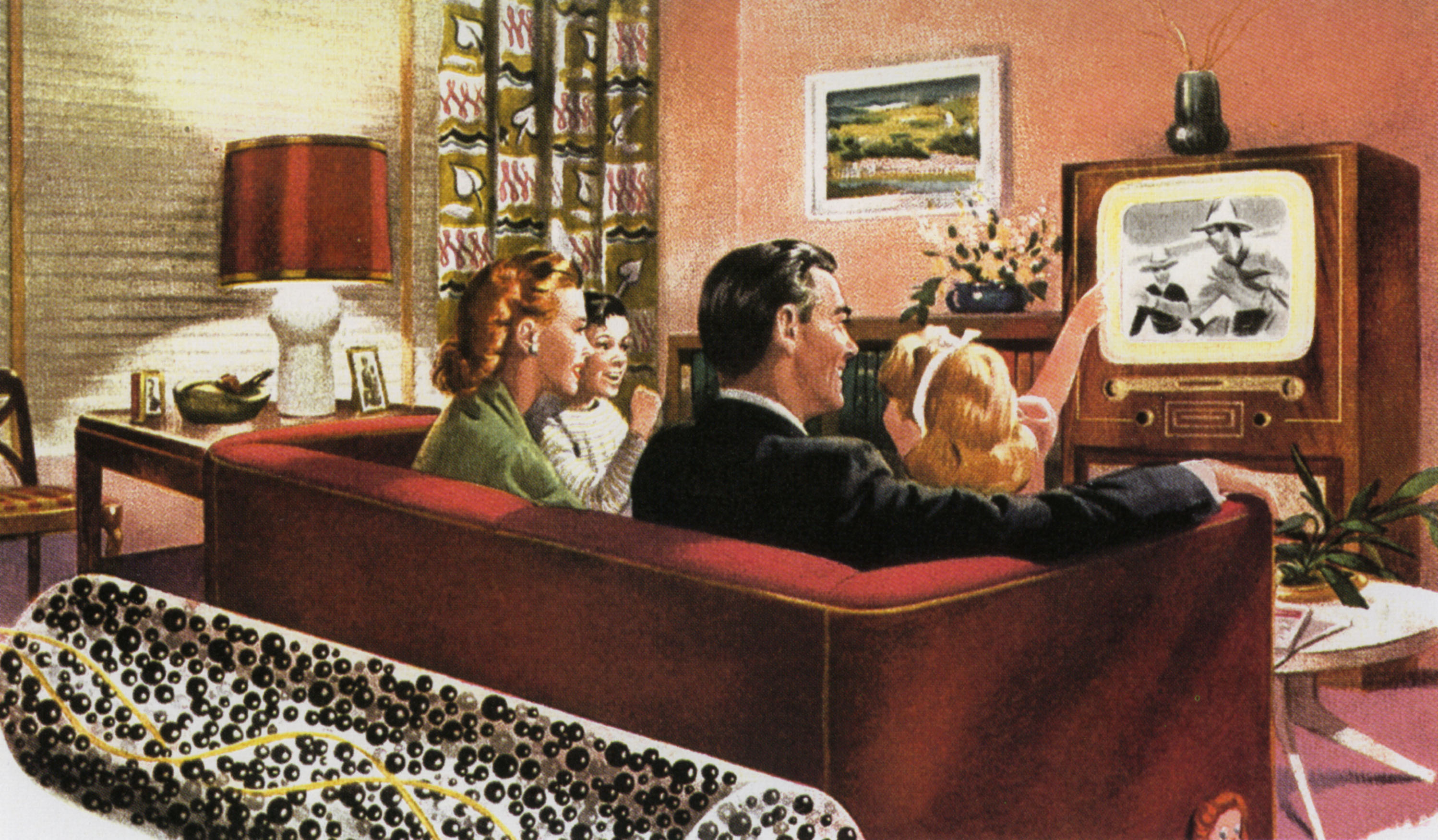

The past is as active a force in the imaginations of reactionary illiberal Catholics like your correspondent as it is in those of the thrice-divorced pro-same-sex-marriage president of the United States and the man who probably should have been his opponent in the 2016 election. President Trump and Bernie Sanders both wish to recreate the economic, if not the social, conditions of the 1950s and early '60s, that supposed golden era of prosperity. It was in large parts thanks to his ability to speak to the nostalgic aspirations of older blue-collar workers in Michigan and other former manufacturing states that Trump was elected.

That the glorious abundance of their youth was built, like Wagner's Valhalla, on an edifice of falsehood and privation — check local UAW rolls circa 1960 for black members the next time you feel inclined to say something glowing about the Big Three automakers and the wealth they engendered — does not occur to many older Americans. The evils of the past can be ignored or papered over; they can be acknowledged and dreamed away with the ill-founded assumption that the future will be very much like the past but in some vague sense better, more moral, more equitable, unbeholden somehow to the assumptions and conditions that made its antecedent realizable.

Nostalgia is frequently a silly thing. But it is also dangerous. James Alex Fields' nostalgia for a past about which he knows nothing of substance is what inspired him to drive to Charlottesville. A childish obsession with the iconography of the Soviet Union and various other antique revolutionary movements is what animates the 20-somethings of antifa to put on absurd costumes when they fight pitched street battles against their LARPing Nazi and Ku Klux Klan opponents.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

While it is important to recognize the limits of this emotion, and to be on guard against the numerous evils attendant upon it, I would like to insist that nostalgia is not only valuable but inescapable, even necessary. This is not because it offers us some sort of illusory glimpse at the world of our ancestors or even simply because it is pleasurable. Nostalgia matters because its origins lie ultimately, I think, in our alienation from a past so remote that there is only one brief account of it in all the world's literature.

It is our yearning for a lost prelapsarian existence in full union with our creator that lies, I think, behind that feeling of rapture that takes hold of us when we contemplate the past, real or imagined. It is the answer to a riddle posed in our hearts when we hear an old song or watch a beloved film from childhood or take quiet walks in late spring or early autumn; it is the musical theme developed in every human life.

Nostalgia is at once an acknowledgment of death and a quiet unbidden reassurance that it is not final.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.