Should tech companies run our cities?

The problems of the Googlopolis

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

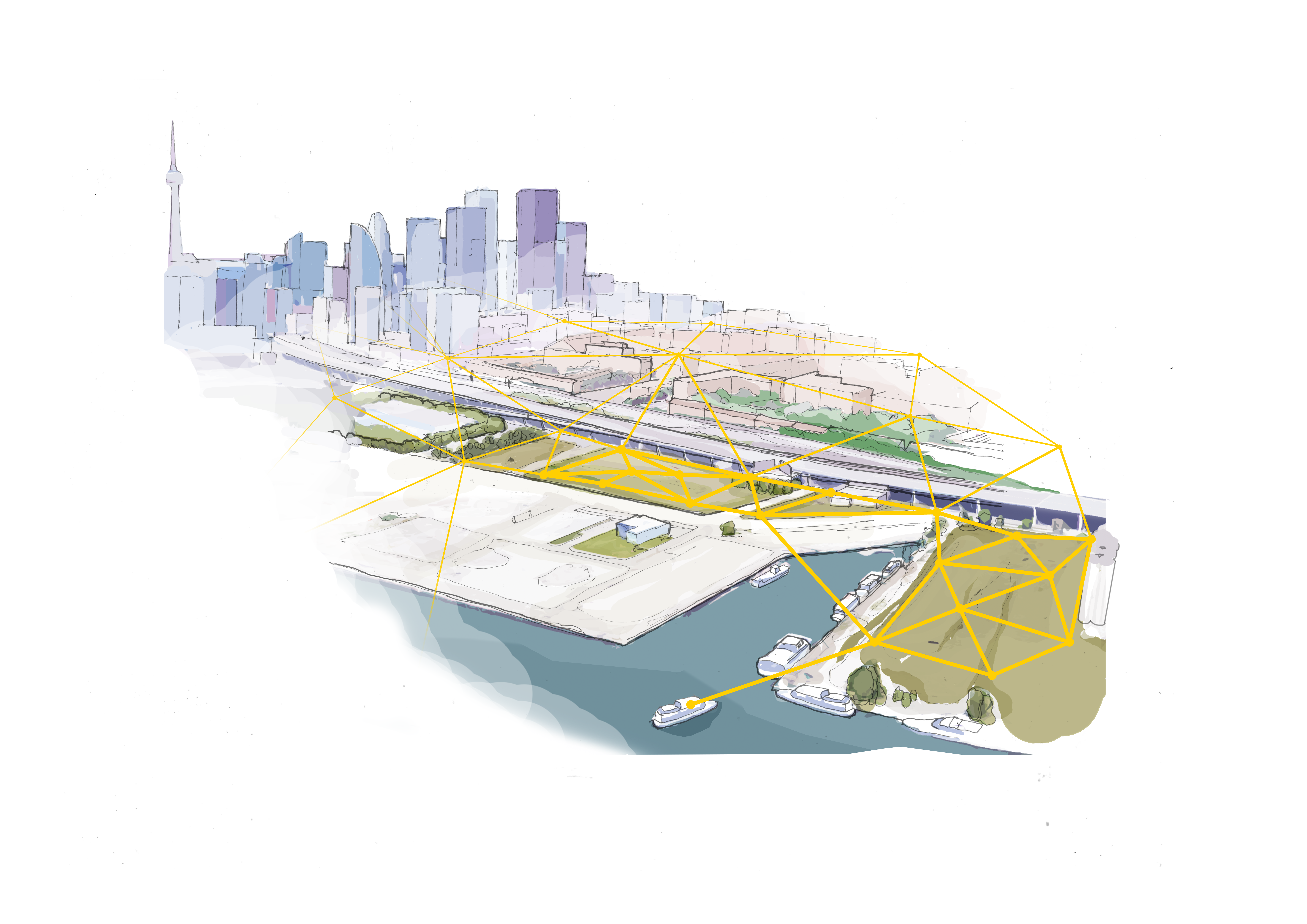

It sounds almost dystopian: One of North America's largest cities handing over a key neighborhood to a tech giant so it can be rebuilt from scratch. That, however, may be exactly what is about to happen. Recently, it was announced that Sidewalk Labs, a division of Google-parent Alphabet, will (pending approval) lead the creation of about a 12-acre district called Quayside in a prime area of Toronto's newly revitalized waterfront area.

But if the plan immediately sounds like the beginning of a sci-fi movie in which things are about to go very wrong, Sidewalk Labs' vision at least is distinctly utopian. Simply put, Google's urban spinoff wants to build a laboratory for how a city should be run, a smart city predicated on tech, data, and everything from self-driving shuttles to garbage sorted by robots — all while shifting its Canadian headquarters to the new district.

The project is emblematic of the ideal that increasingly lies at the core of tech. It reflects a desire on the part of the biggest companies to not simply sell products, tools, or even platforms, but rather to become actual infrastructure. It's not just Alphabet, either; Facebook, Uber, Airbnb, and more are all engaged in shifts that are just as much social as they are technological. That change has rightly elicited a growing sense of ambivalence around not just digital technology itself, but the companies that create and deliver it.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

We are thus stuck here, at the dawn of the new millennium, between needing new, possibly radical ways of organizing not just cities but societies, and the fact that the tech companies who pitch grand futuristic visions are not able to deliver the utopia they promise. And at least one problem is that there is, as of yet, no functional middle ground between the hyper-capitalist aims of Silicon Valley and the sometimes too-rigid systems of government and legacy business that stand in their way.

If no ideal middle ground yet exists, however, harshly criticizing the Valley's ideals is nonetheless fair. Consider: Speaking to The New York Times about the project, Alphabet Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt suggested the Sidewalk Labs idea emerged from asking, "Wouldn't it be nice if you could take technical things that we know and apply them to cities?" He continued: "We started talking about all of these things that we could do if someone would just give us a city and put us in charge." The point is clear: The same kind of data-driven, rapid, and often experimental approach that has allowed tech to innovate and change the world so fast should, at least in part, be applied to cities — an approach that should raise eyebrows. Cities are not only incredibly complex places of overlapping systems, the many different needs of different residents require a sophisticated mix of democratic governance, policy, and private action, not just fancy algorithms and sensors.

Schmidt did qualify his comments to say that there are good reasons that cities would resist the blanket application of his ideas. But his words still reveal a desire to use Google's methods for the web and mobile to fix cities or culture at large with tech — a phenomenon that scholar and writer Evgeny Morozov derisively refers to as "solutionism," mocking the tendency to see simplistic digital answers to complex societal problems.

All the same, there are problems that do need solving. For example, like many other global cities, Toronto has recently become a victim of its own success. Just as has happened in New York, San Francisco, Vancouver, and elsewhere, as residents both new and old pour into the city in search of jobs and a high quality of life, property values have skyrocketed to absurd levels, inequality is growing, while transit and other forms of infrastructure struggle to keep up. Exacerbating these pressures on cities are restrictive zoning practices enforced by backward-looking city governments, residents who resist change, and a lack of financing for necessary infrastructure projects.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In that sense, the Toronto Sidewalk Labs project may symbolically represent an attempt to address entrenched challenges with novel ideas. The plan includes fancy notions like driverless shuttle buses, but also genuinely intriguing ideas like "Lofts," in which buildings are built as adaptable frames that can be modified more quickly to suit changing demographics or business needs. There is also the way in which sensors might do things like monitor noise so that bars or clubs can co-exist with residential areas without one impinging too much on the other.

So there is on the one hand a set of legitimately difficult challenges; and on the other, the companies promising solutions perhaps cannot be entirely trusted — in no small part because they are themselves part of the problem. After all, it was only recently that Google put false news reports at the top of searches during the immediate aftermath of the Las Vegas shootings. It follows growing reports about the ways in which Russian groups may have exploited weaknesses in Facebook and Twitter's systems to foment discord in America and possibly even affect its election. This is to say nothing of how Twitter, after existing for 11 years, still doesn't know how to deal with abuse and harassment.

Simply put: When tech companies end up becoming social infrastructure, they have thus far done a middling job of responding with the appropriate level of social responsibility. Because their focus is on not just the bottom line, but the ideas of neutrality and a reliance on algorithms, tech has often proven not up to the task demanded of it by the very scale that the companies themselves sought.

Tech has thus become like a social infrastructure, but also without the safeguards that decades or even centuries of experience have bestowed upon other forms of infrastructure, like government itself. And this seems to be the tension between the utopian and dystopic dimensions of our grand digital shift: For each legitimately incredible advance, we are presented with a whole new set of problems, the solutions to which only seem to emerge after user outrage. And if we are to hand over portions of our cities to the idea and ethos of digital technologies, perhaps the expansive, exciting ideas of the tech world need an appropriate counterbalance — that is, the systems designed to represent the people who live under them. If we are ever to approach something like a new utopia, it seems that balance is the only true way toward the future.

Navneet Alang is a technology and culture writer based out of Toronto. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, New Republic, Globe and Mail, and Hazlitt.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

How do you solve a problem like Facebook?

How do you solve a problem like Facebook?The Explainer The social media giant is under intense scrutiny. But can it be reined in?

-

Microsoft's big bid for Gen Z

Microsoft's big bid for Gen ZThe Explainer Why the software giant wants to buy TikTok

-

Apple is about to start making laptops a lot more like phones

Apple is about to start making laptops a lot more like phonesThe Explainer A whole new era in the world of Mac

-

Why are calendar apps so awful?

The Explainer Honestly it's a wonder we manage to schedule anything at all

-

Tesla's stock price has skyrocketed. Is there a catch?

Tesla's stock price has skyrocketed. Is there a catch?The Explainer The oddball story behind the electric car company's rapid turnaround

-

How robocalls became America's most prevalent crime

How robocalls became America's most prevalent crimeThe Explainer Today, half of all phone calls are automated scams. Here's everything you need to know.

-

Google's uncertain future

Google's uncertain futureThe Explainer As Larry Page and Sergey Brin officially step down, the company is at a crossroads

-

Can Apple make VR mainstream?

Can Apple make VR mainstream?The Explainer What to think of the company's foray into augmented reality