America's age of erasure

What happens when a mob demands that representations of people or events that fall short of current moral standards be taken down and destroyed?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

No one who cares about the dignity and autonomy of women, or who longs for men to be more than predatory perverts, can fail to be pleased by the recent public humiliation of so many alleged serial harassers and abusers in the worlds of entertainment and journalism.

But that doesn't mean the character and extent of the punishment always fits the transgression.

There's something more than a little creepy about the impulse to excommunicate the perpetrators and their entire life's work from civilized society. If we're not careful, a confluence of runaway moralism and market-driven mania will turn our time into an Age of Cultural Erasure.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The impulse animating the trend can be seen in its purest form in the drive to get rid of statues and other morally tainted symbols from public places. I'm not primarily talking about statues of Confederate generals removed after democratic deliberation. I mean acts of the mob, demanding that representations of people or events that fall short of current moral standards be taken down and sometimes even destroyed.

This is ultimately an expression of iconoclasm — the tendency in moments of transition, unrest, or revolution to tear down and smash symbols of the old order. It began in religious contexts (where iconoclasm played a significant role in the history of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) and then migrated over to politics in modern times, as disputes among far-left and far-right factions have come to resemble the sectarian conflicts of earlier eras. Conquering armies also delight in symbolic displays of iconoclasm, as the U.S. military showed in its televised toppling of a Saddam Hussein statue following the American invasion of Iraq in 2003.

What protesters are demanding when they clamor for the removal of statues and other symbols is that they be denied a place of public honor. But what about when the object of scorn is a person and a body of work instead of a symbol? When that happens, things become more troubling.

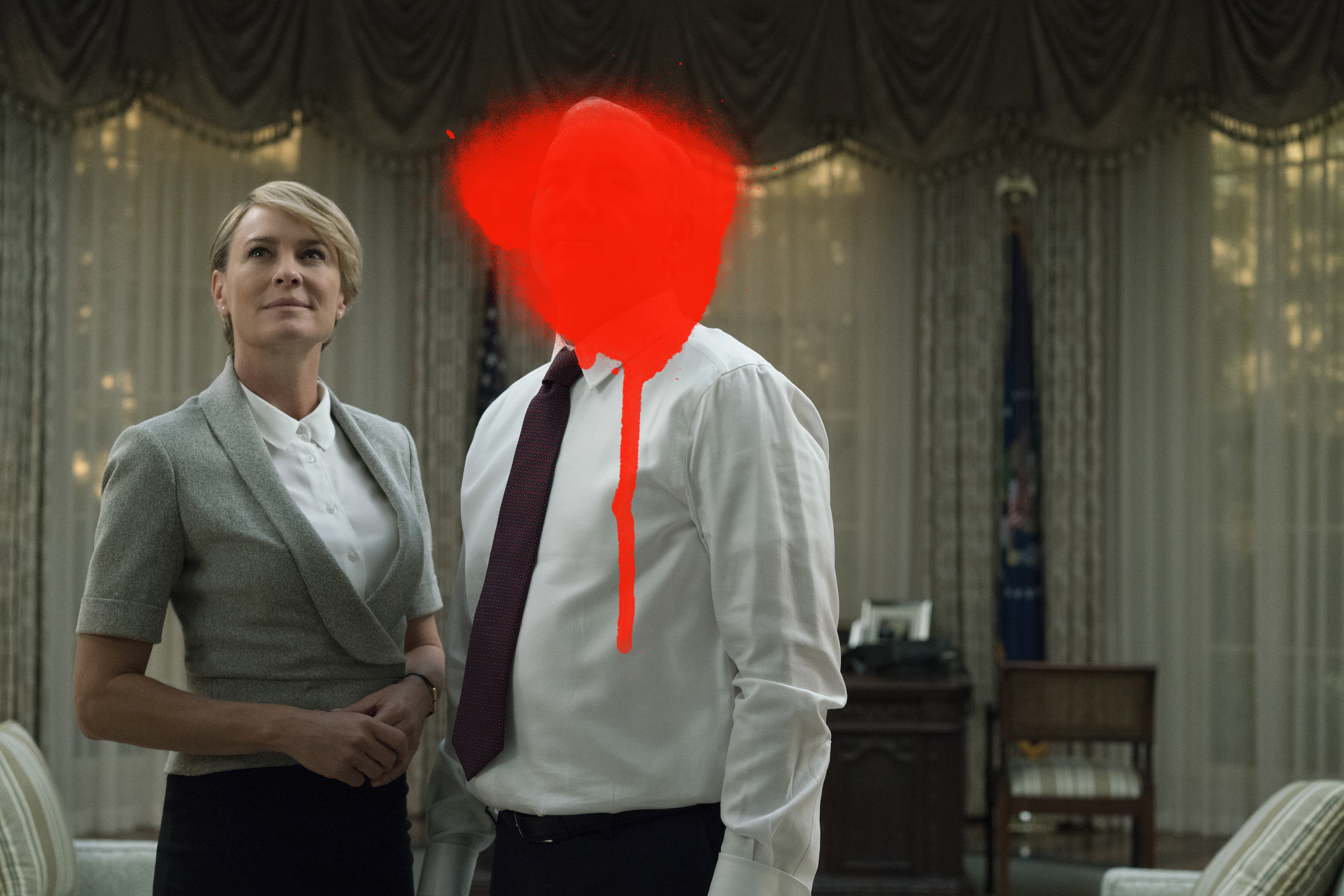

Consider the case of actor Kevin Spacey. In the wake of sexual assault allegations, it makes sense to keep him from situations in which co-workers on a film set might be in danger. But Spacey's career hasn't merely been placed on hold. His long-time agents have dropped him, and most astonishingly of all his performance in a forthcoming movie, which was filmed months ago, has been edited out entirely, with the director scrambling to reshoot his scenes at the last minute using Christopher Plummer as a stand in.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's almost as if Spacey had never existed.

The same drive toward erasure can be seen in the reaction to Leon Wieseltier being credibly accused of sexual harassment by numerous female former staffers of The New Republic. Wieseltier clearly has no business serving in a position of authority over women in a workplace. But did his new magazine need to be shuttered before its first (already completed) issue appeared? And did The Brookings Institution and The Atlantic really need to sever their ties to him completely, including removing him from the largely honorary positions he held at both institutions?

The banishment only makes sense if the point is to ensure not merely that Wieseltier is humiliated and prevented from being placed in a position of authority over female employees in an office environment, but also that he's banished from the cultural life of the nation altogether, like a once-revered icon smashed into dust in a frenzy of recriminations.

What's driving these acts of iconoclasm are not just severe moral judgments — the justifiable desire among the victims of harassment (long denied or downplayed) to see that perpetrators suffer consequences so severe that would-be future abusers think twice before engaging in similar behavior. It's also driven by market imperatives: Avoid bad press! Don't damage the brand! The result is a concerted effort to cut offenders loose from all institutional ties. That way everybody wins.

But do we?

The answer is far less obvious than many presume, especially once we begin to separate out the person from the art he creates. Such acts of separation can be tricky, but they are essential.

A Louis C.K. riff about technological innovation or mortality can still be funny and insightful after the grotesque revelations of the past several days, even if his many routines about masturbation and leering at women have now become nearly unwatchable. So enjoy the good and skip the bad.

Separation in Spacey's case is even easier. He's an actor. Actors are paid to play roles, none of which can ever be conflated with the actor himself. By all means, let the authorities investigate his past actions and punish him legally if the facts warrant it. By all means, make sure no one who works with him is placed in harm's way. But his mere presence in a film, a play, or a TV show doesn't taint it, as if the actor possessed the macabre power to spread evil spirits everywhere he goes.

Perhaps the clearest example of the disjunct between the allegedly atrocious behavior of an artist and the greatness of the work he creates can be seen in the case of film director Roman Polanski, who fled the United States in 1977 after pleading guilty to the statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl. Would the world be a better place today had Polanski been banished from the film industry internationally and prevented from directing the 2002 film The Pianist, among the most emotionally gripping movies ever made about the Holocaust? I have a hard time imagining an argument in favor of such a view, let alone finding it compelling.

The fact is that human beings are flawed, sometimes deeply so. But only in the rarest of cases are they irredeemable, with their transgressions contaminating everything they touch. Far more common are the hard cases, in which those who are morally depraved in one aspect of their lives are nonetheless capable of producing something valuable in another.

Our culture should be forgiving and supple enough to take account of both sides of this complex human truth.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.