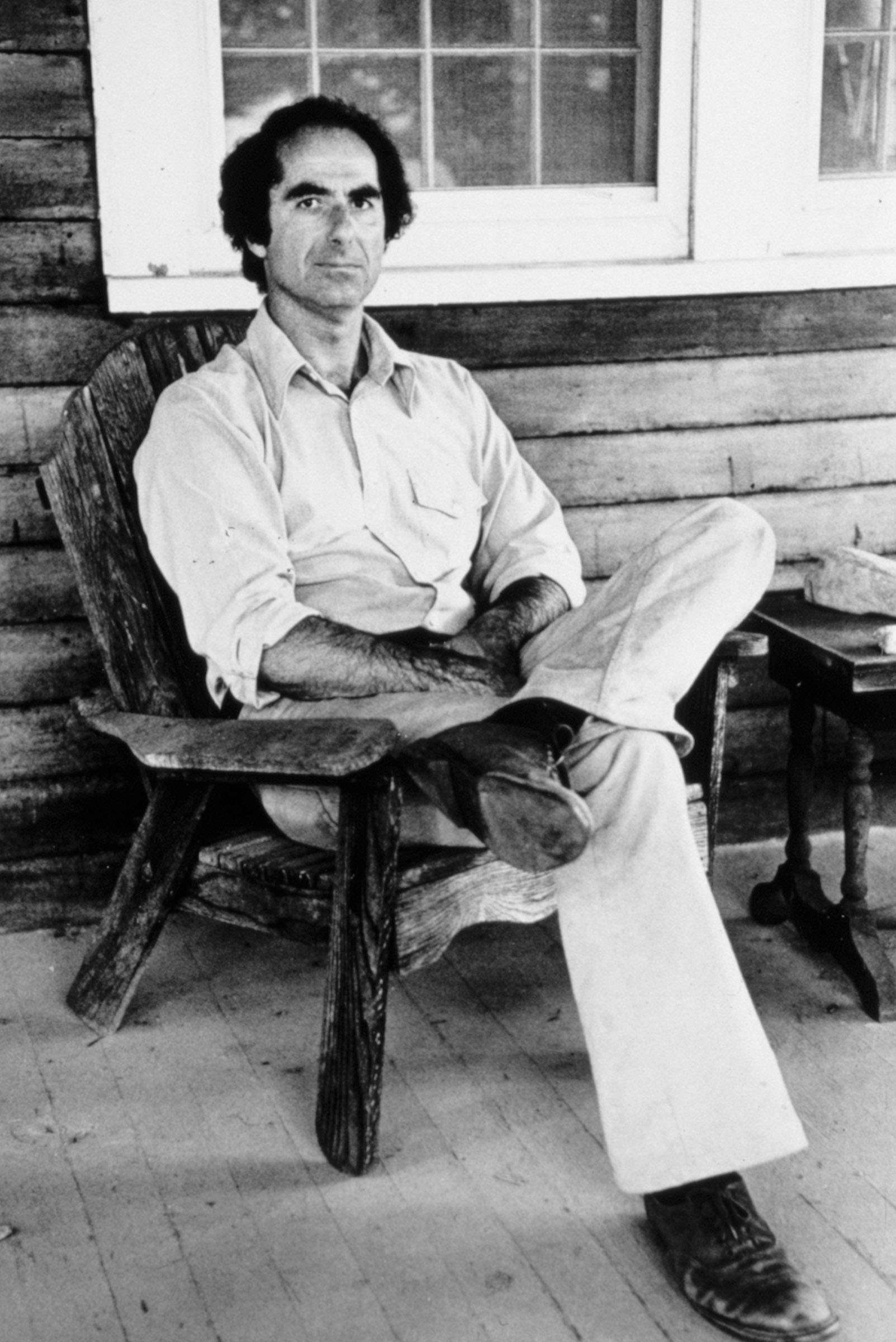

Portnoy's Complaint, and mine

What Philip Roth meant to a young man dreaming of being an author

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I still remember the first time I encountered the late Philip Roth. It was between the yellow covers of Portnoy's Complaint. I don't remember where I was, or precisely how old — late in high school or early in college. But I remember who I was, either way. I was the young man overwhelmed and frightened by his own desires, verbally facile and intellectually ambitious but utterly unable to communicate when it came to the subject of desire, even to myself.

And here, suddenly, was a man who just said it. The obsessive onanism. The frantic sexual desire. The crushing maternal expectation. The conviction that the obsession and desire was perversely connected with that crushing maternal concern. Roth didn't invent these tropes, but he voiced all of it with neither apology nor self-justification. It wasn't brief or a testimony; it was a complaint, with all the loathsome self-involvement that implies — but the titular narrator simply added that to his bill of particulars. Roth had made a monument of his own monstrosity, and I couldn't stop reading.

Portnoy's Complaint is not the book most people will be talking about in their eulogies of Roth. It isn't even my own personal favorite. The Counterlife, Roth's profound exploration of the role of contingency in life, of the way counterfactual thinking can invade and warp the lives we're actually living, and the relationship between this process and the process of making fiction, is both the work of his I most admire, and the one that affected me the most deeply. And plenty of other Roth novels — Operation Shylock, American Pastoral, The Human Stain, and especially Sabbath's Theater — also sit higher in my personal ranking than Portnoy's Complaint. His early masterpiece is a young writer's book — and a young man's book. It's as absurd to treat it as the exemplar of Roth's work as it is to take A Midsummer Night's Dream as the exemplar of Shakespeare's.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But all those greater achievements still add to the luster of that early success, because none of those other books would exist without Portnoy.

Roth began his career with the bracing honesty of the stories of Goodbye, Columbus, for which he was acclaimed by the literary press and condemned by much of his own Jewish community for airing dirty laundry in public and reinforcing ugly stereotypes of greedy, self-centered, and libidinous Jews. If he was to be a credit to his people, he needed to produce work that was worthy of that credit. His first two proper novels — Letting Go and When She Was Good — are widely viewed, in retrospect, like a bid for precisely that credit: traditional, restrained, and all-American. Portnoy's Complaint was the novel in which he gave up that ambition, and seized a more important one: to create himself, and introduce that self he had created to the world.

The introduction didn't go smoothly. Portnoy's Complaint was a scandalous success, and its success infuriated Roth because his book was persistently and simple-mindedly read as autobiographical. Which, of course, it was, in the sense that it was personal — it came from him, from his depths. It was his monstrosity, after all.

But Roth wanted to be lionized for the inventiveness and creativity of his art, not gasped at for what he was willing to admit to. He wanted his life to be his own, his art to be a creation. And so he retreated from the literary world even as he dove headfirst into writing. And, in an ironical reaction to his audience's refusal to give him what he wanted, he turned his art into a meditation on that very dichotomy, putting himself and obvious author surrogates directly into works that over and over turned on themes of self-creation, self-sequestering, and self-exhumation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

There's a facile lesson there about Roth's own counter-lives: the one where he continued on his early path and wrote well-regarded but conventional novels; the one where he capitalized on his post-Portnoy celebrity to become Bret Easton Ellis avant la lettre. But there's a deeper lesson for me, about my own counter-life.

When I graduated from college, my ambitions were downright Rothian. I read James Joyce and Franz Kafka, I. B. Singer and Bruno Schulz. I was working on a big novel that grappled with the traumas of Jewish and familial history, with a protagonist that my friend referred to as the YMNUM ("Young Man Not Unlike Myself"). I fantasized about that self I was creating through that book, and introducing it to the world. It was going to be big. I was going to be big.

I never finished the book. One can say that life intruded, and of course it did, but life only intrudes when you let it. I let it because I wasn't willing to expose myself to the kind of censure Roth endured. I was enraptured by Portnoy, but not nearly brave enough to admit to the kinship I felt, much less to attempt Roth's audacity in writing it down.

I'm trying again now, exhuming the kid I was and asking him to speak for himself, whatever it is he chooses to say. I'm highly conscious of the time past, the clock that Roth heard ticking for decades now, and that in his last several novels he turned into his final theme, though that was also there from the beginning, even in Portnoy. But I take some comfort from Roth's long, incredibly fruitful career that it is possible for any of us to live many lives.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.