Trump is discovering trade wars are hard to win

Whoops!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

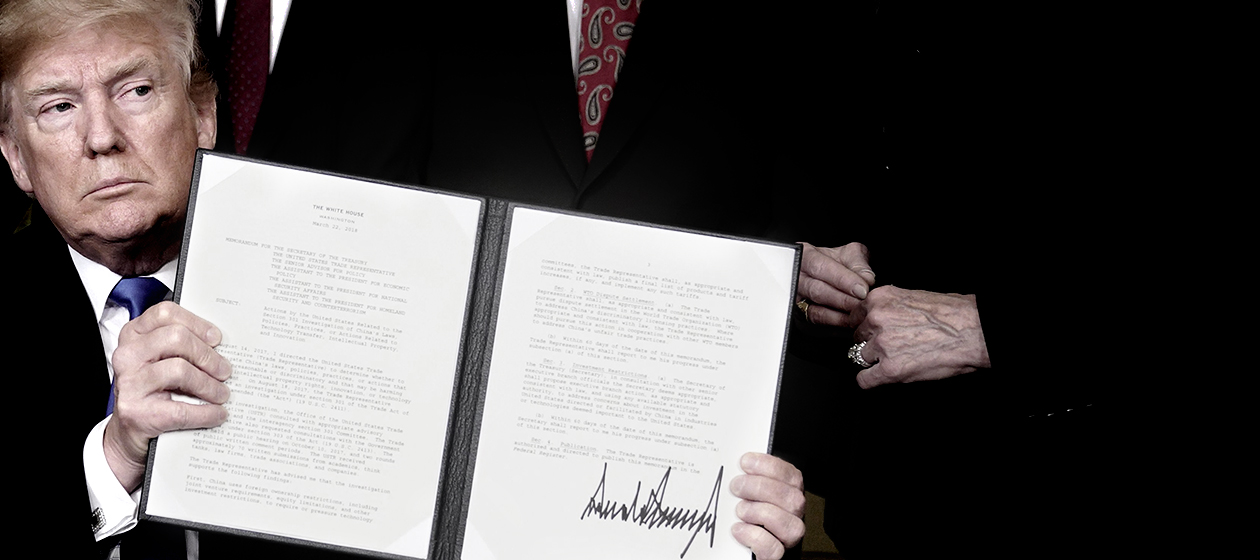

President Trump's trade war with China is proving a lot harder to win than he anticipated.

It's not for lack of effort, of course. The president has already imposed 25-percent tariffs on $50 billion of Chinese exports to the United States. He's teed up another $200 billion worth of 10-to-25-percent tariffs, and he's toying with another $267 billion worth of them. Should Trump go through with the last threat, it would effectively mean U.S. tariffs on everything China exports to the U.S.

In theory, the point of all these tariffs is simple: to bring more jobs and production to America. If U.S. consumers can't purchase goods more cheaply from abroad, they'll bring their demand to domestic producers. That's the idea, anyway. But it's tricky in practice.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For an example, you only have to look at a recent Trump tweet:

What Trump is referencing here is Ford's announcement back in August that one of its hatchbacks, the Focus Active, will not be coming to America. The car is built in China, and with the new tariffs coming in, Ford won't be able to hit its profit targets by selling them in the U.S. Trump apparently got wind of this decision over the weekend, and, consistent with the aforementioned theory of tariffs, he immediately hailed it as a victory.

Except Ford hasn't brought production of the Focus Active back to America. "It would not be profitable to build the Focus Active in the U.S. given an expected annual sales volume of fewer than 50,000 units and its competitive segment," Ford said.

Imposing tariffs can be a lot like a game of whack-a-mole. Supply chains these days are complex with almost endless options for adaptation. Sure, Trump's tariffs will make Chinese goods more expensive. But America is an advanced economy with high wages; there are many countries out there in various stages of economic development where goods can be made more cheaply. Ford has plants in developing countries other than China, such as Thailand or Vietnam, that could presumably build the Focus Active if the company really wants to sell in America. Or it may just decide the market for that particular car is niche enough that it can live without U.S. sales.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Tariffs tend to be more effective as ways to protect a particular industry from the entire world. Think of Trump's steel and aluminum tariffs, which were ostensibly aimed at all those imports no matter where they were from. But even in this case, there can be political blowback or unintended consequences for other domestic industries that use the now more-expensive product. Even economists inclined to be sympathetic to Trump's steel and aluminum tariffs in principle are not entirely on board. For a still-developing economy, this sort of industrial protectionism can make a lot of sense. For an advanced economy like America's, deeply entangled in global markets, it's not as obvious.

That said, tariffs do serve an important purpose.

Instead of being a permanent economic policy in and of themselves, tariffs can impose short-term pain on a trading partner to get them to come to the bargaining table. The point is to reach a broader deal, after which the tariffs can be removed.

Again, in theory, this is what Trump is up to with China. The administration has a list of demands, from closing the yawning trade gap between the two countries to protecting American intellectual property.

But in practice, Trump's team seems incapable of doing a deal. Corporate leaders and Wall Street figures have been attempting shuttle diplomacy between the two countries for months. The goal is basically to explain the administration's thinking and demands to the Chinese. But this is proving difficult, even as China desperately scrambled to put together a new round of meetings this month. Chinese and American officials used to hold semi-annual meetings, first established back in 2006, to hammer out exactly these sorts of misunderstandings. But Trump's White House halted the practice. Hence China's increasing reliance on private business leaders with some sway in the administration.

"The Chinese can't really get their heads around the fact that there's nobody to deal with [in the Trump administration]," one person who recently met with the Chinese told the Financial Times. "They can't get a trade deal or even a framework for a deal."

This is consistent with broader reports of chaos with Trump's team. When it comes to trade, the White House is riven between multiple factions, and there's no cohesive process for working out those disagreements and presenting a unified front. "The Chinese know they will eventually have to make some serious concessions, but they don't really know what they are and who really speaks for the president," one Wall Street executive told Politico in July.

Essentially, the Trump administration is threatening to break China's kneecaps unless they pay up. But when the Chinese try to figure out who to give the money to or even how much to pay, they discover the administration itself doesn't know.

Meanwhile, Trump seems to think the way to solve this impasse is just to swing the tariff bat even harder. We'll see how well that strategy works out.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day