The slow-motion collapse of the American health-care system

Neglect and complexity are killing tens of thousands of people

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America is in sad shape. Despite the strongest economy in at least 20 years, life expectancy has declined on average for the third straight year — which has not happened since World War I and the 1918 flu pandemic. This is driven mostly by an appalling rate of suicide, which has increased by 33 percent between 1999 and 2017 to the highest level in half a century, and the rate of drug overdose, which has increased by a staggering 356 percent over the same period.

There are certainly some cultural and economic factors here, particularly the very high rate of firearms ownership in rural areas (which makes suicide attempts more deadly), and the social dislocation from de-industrialization (where overdoses are concentrated). But another is America's bloated, Kafkaesque nightmare of a health-care system, which is slowing collapsing before our very eyes.

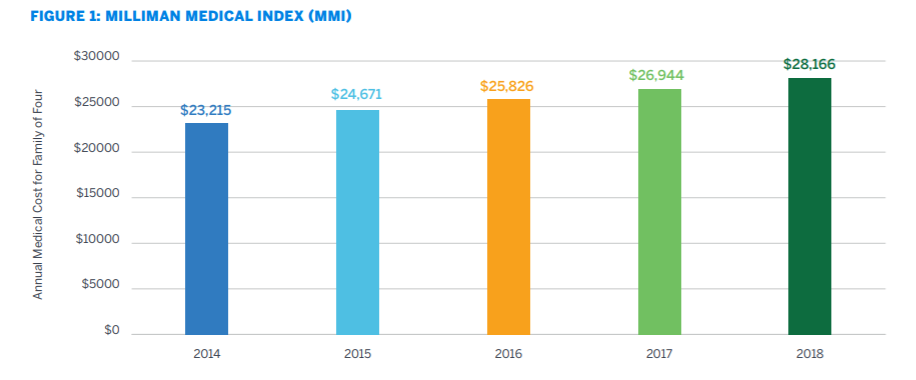

Let's examine two facts. The first is the typical cost of health care for a family of four on an average employer-sponsored plan, taken from a Milliman Research Report. It has increased almost $5,000 just from 2014 to 2018, to $28,166.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Note the median household income in 2017 was $61,372, and health-care costs have exceeded income growth by a long shot for decades.

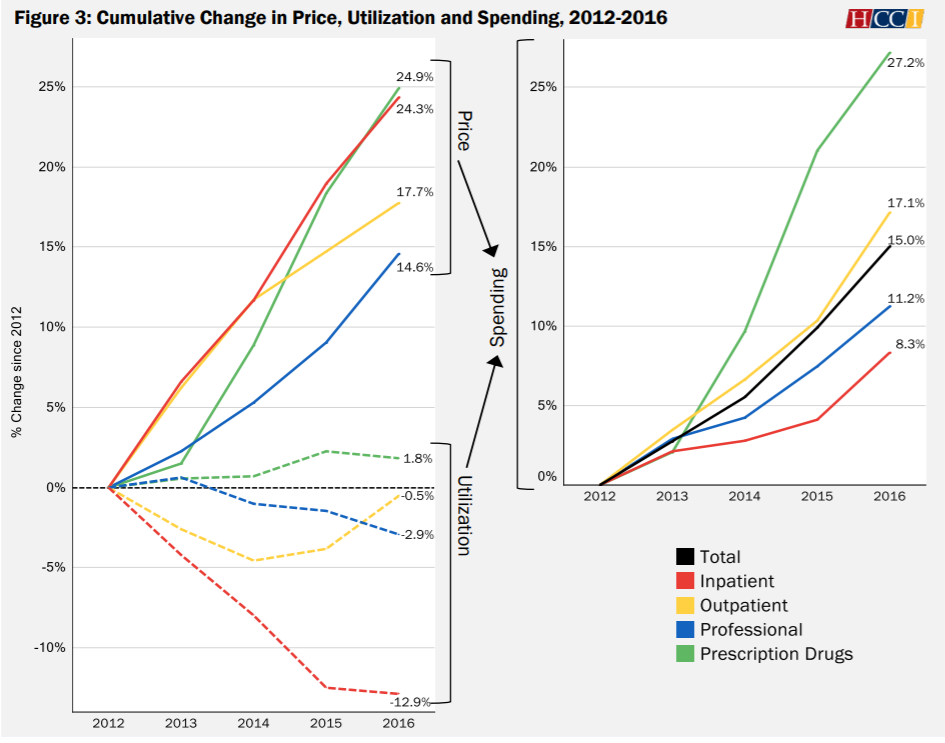

The second is what is being bought with that increased money. Despite the huge increase in spending, the answer is less health care for everything except prescription drugs. As this chart from the Health Care Cost Institute details, skyrocketing costs have pushed people away from treatment — especially inpatient care, which declined by nearly 13 percent from 2012 to 2016.

The American health-care system is a hellish tangle of bureaucracy, the various (often-deadly) inefficiencies and injustices of which would take several shelves full of books to describe. But these two trends paint a decent broad-strokes picture of what's happening: Americans are paying more for less. We are pitilessly soaked for health care — worse than any other country, by far — and getting steadily less actual treatment for our money.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

By definition, drug overdoses are at least in part a medical issue. Over the last few years, as overdose deaths have approached a yearly total of all the U.S. soldiers killed in the entire Vietnam War, then surpassed it, by a lot, an overwhelming amount of research has been published about effective overdose and addiction treatment. Yet even insured addicts often do not receive treatment, and anti-overdose drugs are still only partly available across the country. Adults on Medicaid are more than twice as likely as those on private insurance to get inpatient hospital treatment for substance abuse disorders, more than three times as likely to get outpatient rehab treatment, and eight times as likely to get outpatient mental health treatment.

On the other side of the equation, a sensible health-care system would have done something about for-profit drug companies who used bribes and high-pressure sales tactics to stuff states like West Virginia full of opioid pills, to create as many lucrative addicts as possible.

Suicide is also amenable to medical treatment. For example, a remarkable Jason Cherkis article in HuffPost details an old study that examined simply sending scheduled form letters to people who had attempted suicide over several years. The result was that over the first two years, the suicide rate among the control group was almost twice as high as among the treatment group. (Social isolation, it seems, is a big risk factor for suicide.)

But this kind of relatively simple procedure is very difficult to fit into the Byzantine American health-care apparatus, with its sucking quagmire of payment bureaucracy, constantly shuffling mix of providers and insurance networks, and worst of all, the absolutely amoral grasping for profit from all sides at all times. Hard to find the customary 80-percent profit margin on a simple letter-writing program.

So to a great degree, the overdose and suicide epidemics are just playing themselves out.

America already pays enough to fund two generous universal health-care systems for its citizenry. In a sensible country — that is, one which was capable of passing broadly-popular legislation more than once every 20 years — hundreds of thousands of avoidable deaths would have long since been recognized as the public policy emergency they clearly are, and the whole health-care system would be reoriented accordingly. But until we get another chance to overhaul American health care, the right way this time, coroners and coffin-makers will be working overtime.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.