How to pay for Medicare-for-all

Squeeze wasteful and abusive providers to provide a really good program for cheap

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Medicare-for-all sounds great, but how do we pay for it?

In a normal country, the answer would be simple — just raise taxes. But in the United States, health care is so outlandishly expensive that the simple solution is anything but. Where Austria or Finland would be assured that a modest tax hike could (and did) cover everyone, America has to grapple with a bloated health-care sector eating up over 17 percent of GDP — nearly 5 points (or about $1 trillion) greater than Switzerland, the second-most expensive country.

As Jon Walker argues, this reality forces Medicare-for-all advocates into one of two basic choices, neither of them easy:

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

1. Swallow the huge costs, shove through a really big tax hike, and hope that people will understand the taxes-for-premiums swap.

2. Try to cut costs, and keep the tax increase modest, but tempt the wrath of the medical lobby.

Some tax increases are certainly inevitable. But the second choice is by far the best, on grounds of both practical policy and politics.

When writing a Medicare-for-all bill, it is critical for legislators to understand that traditional Democratic logrolling — in the form of policy carveouts for powerful interest groups — will create more problems than it solves. The way to make the legislation work is to isolate the sources of the most hideous and immoral waste in the health-care system and concentrate the pain on them, so as to provide a really excellent benefit for the broad population with a minimum of necessary new taxes.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To explain why, let's start with the most basic question: Why is American health care so expensive?

One supposed explanation that received enormous attention during the debate, passage, and implementation of ObamaCare is "overutilization." This idea posits that Americans are getting way too much treatment due to the fee-for-service structure of many medical payment plans and "defensive medicine" from doctors worrying about litigious patients. A big Atul Gawunde article in The New Yorker in 2009 made a strong case for this being the major driver of excess medical spending. A white paper back in 2012 purported to demonstrate $210 billion in unnecessary services.

Thus ObamaCare included a "Cadillac Tax" on generous insurance plans, which would have capped the tax exclusion for employer-provided insurance (it has since been delayed until 2020). Economists dislike the tax break because, according to their way of thinking, it "distorts" labor markets in favor of health-care benefits instead of wages, which might lead to over-treatment and increased health-care spending. (Without "skin in the game," people will just spend every day inside an MRI machine.)

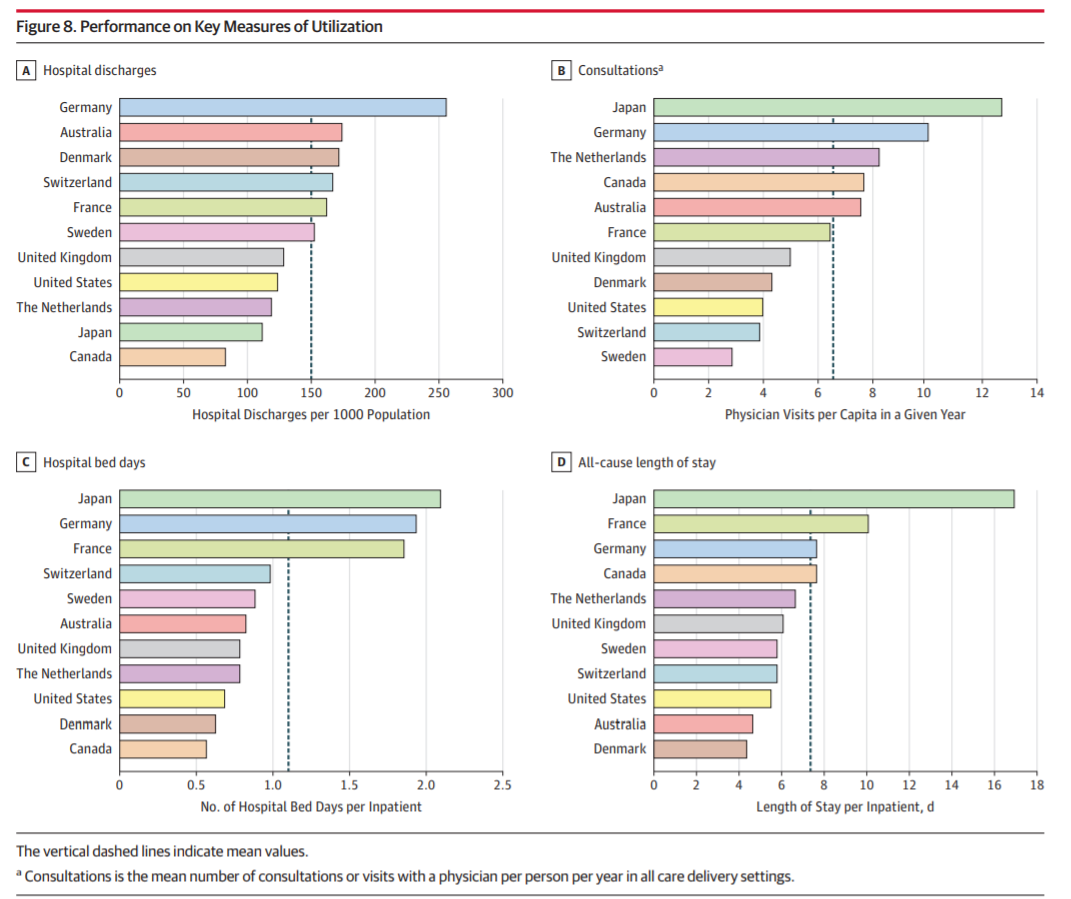

A careful, peer-reviewed international comparison done by Irene Papanicolas et al. in the Journal of the American Medical Association since that time demonstrates conclusively that the overutilization narrative was a gigantic analytical error. Compared to peer nations, Americans do not go to the doctor all that much, ranking actually towards the bottom on broad measures of utilization:

We are at or near the top on scans, knee replacements, cesarean sections, and bypass heart surgery, but only by a small margin — not anywhere close to enough to account for a trillion bucks a year.

Elsewhere, the economist argument that fee-for-service must be juicing spending has not held up either. Maryland undertook a major reform to many of its hospitals, moving to a "global budget program" in which several hospitals were paid a lump sum for the whole year instead of per procedure. A study released this year found it "did not reduce hospital use or price-standardized spending as policymakers had anticipated." Moreover, many other countries have used fee-for-service billing (both today and in the past) and have not experienced anything like America's turbo-charged cost increases.

So what is going on? Returning to the Papanicolas study, two big, obvious things jump out: drug prices and administrative costs. America paid roughly twice the rich country median for drugs in 2015, at $1,443 per person, with $1,023 of that in the form of retail pharmaceuticals. France paid $697, while the Netherlands paid just $466. Secondly, fully 8 percent of American health-care spending goes to administration — as compared to Germany at 5 percent, Canada at 3 percent, or Sweden at 2 percent.

Thus the first priority for a Medicare-for-all bill must be to cut administration spending to the bone. Given that this is largely down to providers having to navigate the hellishly complex and fragmented status quo system, this should be quite easy. Aiming for Canada's level would be a good goal, since it would be a fairly similar program (and global budgeting can help here). Using 2015 figures for consistency, getting down to 3 percent saves about $160 billion (5 percent of $3.2 trillion) a year.

Smashing down drug prices would be harder politically, but conceptually simple. As Japan's medical price regulator does, you simply survey the drug market and set prices given an overall budget of (let's say) $725 per person. That's still on the high side among rich countries, allowing for higher prices for drugs requiring expensive development and production, but with the main objective of halting rampant, merciless price-gouging. Given that 84 percent of U.S. drug consumption is generics, this should almost exclusively hurt Big Pharma companies charging rip-off prices — as they charge Americans more than twice the U.K. price for arthritis medication Humira, more than three times the U.K. price for cholesterol medication Crestor, more than three times the German price for diabetes medication Lantus, and more than four times the French price for asthma treatment Advair. The Medicare price-setting board should also have the power to force recalcitrant pharma companies to license their patents (which are a government-granted monopoly in the first place, after all) to a generics manufacturer if they won't play ball with a valuable treatment.

That saves another $230 billion, for a total of $390 billion.

Now comes the hard part. The other big, obvious cost difference in the Papanicolas study is doctor salaries. American general practitioners make considerably more than in other countries, and specialists make dramatically more. American GPs made $218,000 in 2015 on average, compared to $146,000 in Canada or $112,000 in France. U.S. specialists rake in $316,000, compared to $192,000 in the Netherlands or $153,000 in France. Nurses make more as well, but not by such a huge margin.

This huge discrepancy is not just — or even primarily — about doctors (all doctor salaries combined are only about $200 billion). Instead it's the most obvious symptom of a general cost bloat throughout all medical prices. Papanicolas didn't study services directly, but the Kaiser Family Foundation has, and their collection of data shows that compared to peer nations, Americans' angioplasties and bypass surgeries cost two to three times as much, deliveries and c-sections about 50 percent more, MRI scans two to four times more, appendectomies two to five times more, and on and on. Across virtually all medical services, Americans are being radically overcharged.

Indeed, many hospitals don't have the slightest idea of what their treatments really cost. As this Wall Street Journal report explains, when a Wisconsin hospital tried to figure out what it was clearing for a $50,000 knee replacement, after an 18-month investigation it found a mere $10,550 at most in overhead — and that's including steep U.S. doctor salaries. A roughly 80 percent profit margin on the most common non-childbirth surgical procedure is the kind of thing that could begin to explain the howling excess of U.S. medical spending.

Other providers operate on pure mafia logic. One recent Kaiser Health News article tells the story of a man who had a heart attack and ended up in an out-of-network hospital in Texas. Even after his insurance paid out almost $56,000, the hospital reportedly stuck him with a balance bill of $109,000 — all for a procedure an expert estimated should be charged at about $27,000. Most tellingly, when national media swarmed over the story, the hospital reportedly cut the bill down to … $782. There was no financial necessity whatsoever; they were just going to squeeze this guy of his every last penny, but backed off when their (quite legal) scheme got too much attention.

Obviously, if many hospitals don't even know what their internal cost structures are, then it's impossible to provide accurate aggregate figures on this kind of waste and fraud. However, one initial study found 50 hospitals charging routine 10-fold markups, and preliminary government chargemaster data on common services found wild price discrepancies between providers. We can certainly say the amounts involved are very large, and that is where the bulk of the remaining excess spending lies.

Therefore, the new Medicare agency would need to wage an all-out war on cost bloat and waste. As detailed above, it should immediately smash down administrative costs and drug prices. For services, it will probably have to start by mandating all providers use existing Medicare prices, which will save a considerable amount right out of the gate. But the agency should immediately conduct an extensive national audit of provider cost structures to root out waste and fraud, and adjust prices accordingly.

It's impossible to say precisely what effect all that would have on providers. Most would probably end up largely fine, with lower prices but less administrative expenses and some countervailing new revenue from the newly insured. A small fraction of overtly predatory providers would likely go bankrupt — but they could be restructured into normal providers. Doctors (a majority of whom now support Medicare-for-all, by the way) would be mostly fine, with perhaps a slight pay cut for GPs compensated by a radical reduction in paperwork (which currently eats up a sixth of physician time) and a bigger cut for a minority of particularly overpaid specialists. Ultimately, there's no reason to think that providers can't get by on prices that would still be high by world standards.

But the biggest ones should also be broken up. As Philip Longman argues, a Medicare-for-all bill should roll back provider monopolization (itself a major driver of cost bloat), by busting big providers and holding companies to ensure significant competition in all health-care markets. In theory, a national Medicare regulator should be able to force even giant provider pools to just accept cheap national prices, but they pose the political risk of being able to force through price increases through lobbying — and on the other hand, there's basically no downside to cracking them up. If there's even a chance of it helping things along, it should be done.

Now for the final accounting.

If we start with that 5 point GDP gap (or $1 trillion) between the U.S. and Switzerland in annual health-care spending, drugs and administration cuts get us about 2 points (that $390 billion from above). As I noted above, it's hard to say how much waste and fraud will cover with any certainty, but I would venture it would be about 2 points ($400 billion) at a minimum.

In my view, a national Medicare-for-all plan should make up the remaining difference in tax increases and actually aim for an overall spending goal of 1 point of GDP higher than Switzerland. (This is an arbitrary choice, but it's trying to strike a balance between cutting a hard bargain and setting realistic goals. A bit more revenue will grease the policy skids.) Government health-care spending through direct programs and tax expenditures already accounts for about $7,000 per person. Assuming that can all be captured and redirected, that leaves about $650 per person — or $210 billion total — in more revenue to bring us up to 13.3 percent of GDP. The existing progressive 2.9-3.8 percent Medicare payroll tax brings in $260 billion, so another payroll tax of 2-3 percent ought to carry that easily. Alternatively, we could add a new income tax surcharge, or some mechanism to force the rich to pay more. The point is that is a modest, easily achievable tax.

This new revenue might not be enough at first, requiring some initial borrowing, but any remaining budget gaps will be made up through the price cuts and audits outlined above. Of course, we won't know for sure how much we can save until we start really trying, and all these estimates are very rough. But it basically has to be the case that America can wring out enough waste and bloat to have merely "the world's most expensive health-care system by a small margin" instead of our current wild outlier status.

This finally brings me to the politics. Pressing down hard on costs provides a corresponding benefit — the ability to offer a really, really good plan for cheap. Instead of providing a tax increase about as big as current premium payments and cost-sharing — about $28,000 on average for a family of four, which would be an enormous payroll tax of perhaps 10-25 percent — it would be a meager little tax. Virtually every non-rich person would come out way ahead, creating a gigantic constituency for the new program instantly. People would be slavering for that kind of coverage. Meanwhile, the wildly dysfunctional health-care sector would finally be put in something approaching a rational order, removing a major drain on wages and productivity.

The medical lobby has helpfully clarified the issue by coming out guns blazing against Medicare-for-all sight unseen. The way to get over that obstacle is by offering a spectacular benefit to the rest of the population, something that would mean permanent high-quality coverage plus significant extra take-home pay. Selling that benefit hard, whipping up energy and demand around it, and assailing those who would stop it might just carry Medicare-for-all over the finish line. But doing the Democrat Cringe and trying to forestall criticism by pre-compromising with interested parties — as ObamaCare was passed — will deflate base enthusiasm with higher tax needs while failing to win over the special interests.

The medical lobby will kill Medicare-for-all if they can, and the best way through is to bulldoze it.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.