The year we lost faith in technology

2018 was the year tech companies became the enemy

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's a classic trope in movies: The character you thought was the good guy pulls off their proverbial mask to reveal that — gasp! — they were the enemy all along. In a nutshell, this is the story of Big Tech in 2018.

In recent decades, the digital revolution was ushered in by some scrappy upstarts who upended industries and changed the world in a flash of creativity and cascades of money — not to mention offices filled with puppies and foosball tables. It all seemed so magical. We optimistically anticipated the many ways tech and digital innovation would make our world a better place. But then, as social media became ubiquitous, we began to worry: Are people no longer living in the moment? Have we lost the ability to speak face-to-face? Things got darker: There were harassment campaigns, Gamergate, hate groups openly congregating on Reddit. Next came the rise of the alt-right, fake news, and of course, the ceaseless noise and acrimony of the Trump era.

Here, at the end of 2018, I think one thing has become abundantly clear: Tech is now the enemy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This may seem like a hyperbolic position to take. But consider what we've learned in a year during which tech companies suffered an onslaught of embarrassing communications leaks, and were hauled, one after another, in front of governing committees to answer for their sins.

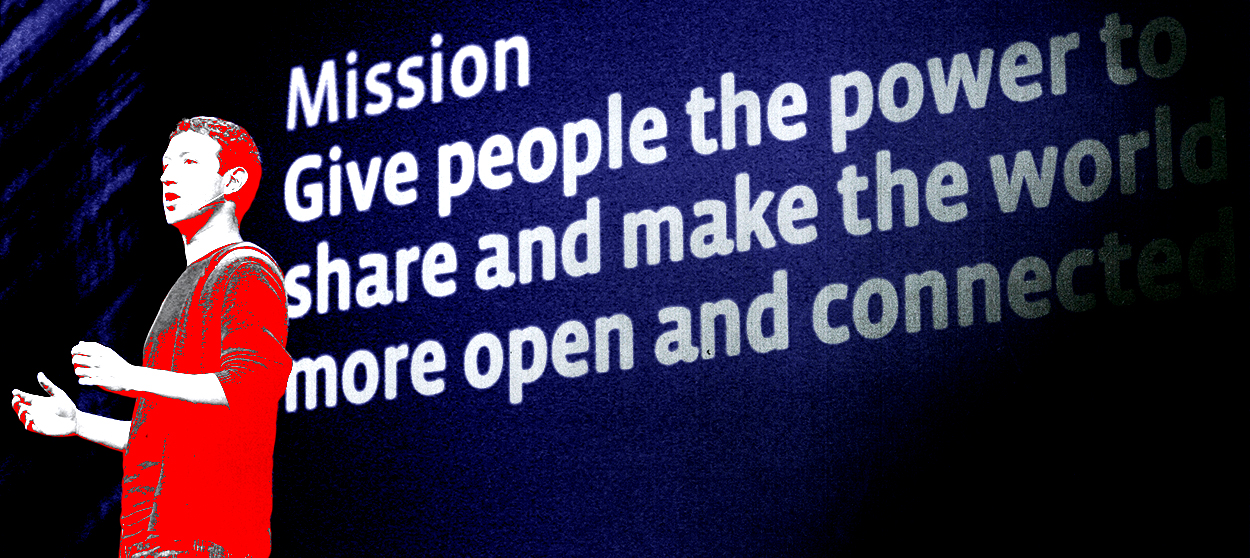

Facebook is perhaps the worst offender. Recently, a series of emails between Facebook execs revealed that Facebook sought to track Android users' call logs without permission. In another instance, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said in an email that what "may be good for the world" isn't always good for Facebook. If there was any confusion, Facebook's attempt to appear a force for good only masks its own self-interest. After all, this year, as scandal after scandal unfolded for Facebook — the Cambridge Analytica one being the biggest — Facebook tried hard to deflect and deny accusations against it, often in dubious ways. In short, it acted like all big businesses eventually act.

It's not just social media companies that are the villains here. Google CEO Sundar Pichai testified to Congress about potential bias in the company's products. While it's true that some of the bizarre questions from Congress exposed a deep misunderstanding of how the internet actually works, the sheer complexity of Google's multi-faceted tracking demonstrates exactly why the search giant should be regulated: Tech companies deliberately make their behavior hard to understand.

There is also the broader imbrication of tech and the government. Consider the controversial child separation policy imposed by President Trump's administration. Despite some criticism from a handful of tech executives, many companies — including Palantir, Dell, and HP — are providing ICE with technology. Microsoft president Brad Smith also proudly asserted that the company wants to help the U.S. military, saying it is Microsoft's responsibility to provide the best to the country's forces. While one can of course take differing perspectives on armed conflict, to assert that the American military is indisputably good takes a clear side in that debate.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Meanwhile, tech companies are tracking our locations, often in confusing, ethically murky ways. But if tech companies' practices and beliefs are one part of the equation, the other is their sheer scale. Facebook's user base is staggering: 2.2 billion people have accounts. The company has an annual revenue of $40 billion and a net income of $15 billion. This is historically unprecedented. As John Herrmann writes in The New York Times, today's tech titans have so much money that they are not so easily disrupted; rather, they may linger for many years, not least because the user data they hold is so valuable.

We also know that social media can have a variety of ill effects on mental health. While tech companies have made some steps to counteract this trend, they are hamstrung by the fact that their business models rest on getting users hooked and keeping them coming back for more.

Tech is thus the new establishment: a collection of powerful actors who have their own best interests at heart. Our headlong rush into digital is no longer new, and the tech giants who ushered in this era are far from the scions of a grand new age. Instead, they are our adversaries.

Of course, one might argue that big tech still provides utility. I myself am grateful that WhatsApp allows me to keep in touch with family thousands of miles away, and that Twitter connects me with like minds, and that Google lets me find information I never would have otherwise. That there is value in digital tech is inarguable. But to live in the 21st century is to be inevitably bound up in things much bigger than yourself. You might oppose the oil industry but out of necessity have to use plastics or drive a car. Big tech's usefulness doesn't negate its increasingly worrying behaviors.

History has borne out the idea that confrontation between power and those who are subject to power is the only way anything changes. We ordinary people — and the press and politicians who represent us — have to accept that big tech companies are bad. Only through realization and resistance can we find a way to something better, something healthier, and something vastly different than tech's turn to avarice, insidiousness, and harm.

Navneet Alang is a technology and culture writer based out of Toronto. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, New Republic, Globe and Mail, and Hazlitt.