Can psychics speak to the dead?

A band of skeptics infiltrates audiences to prove that famed psychics are frauds. But sometimes the power of these 'readings' is hard to deny.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Adapted from an article that originally appeared in The New York Times Magazine. Used with permission.

When you're setting up fake Facebook pages, it's the little details that can mess things up.

On a group computer call last winter, Susan Gerbic was going through her checklist of tips for her team's latest sting operation — this one focused on infiltrating the audience of a psychic. It all started with maintaining their Facebook sock-puppets — those fake online profiles. "American spellings, everyone!" she commanded her half-dozen international colleagues through the Skype crackle.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Gerbic lives in Salinas, California, and while she is retired from the routine world of work, she has taken on a new job, as self-appointed guardian of Enlightenment Reason. She spends most of her days wrangling her far-flung group of Guerrilla Skeptics into a common cause, defending empirical truth online. This usually consists of editing and monitoring Wikipedia pages — a cat-herding task she says she's uniquely qualified for. "I was a baby photographer," she explained. "I ran a JCPenney portrait studio for 34 years."

Collectively, the group, which has swelled to 144 members, has researched, written, or revised almost 900 Wikipedia pages. Sure, they take on the classics, like debunking "spontaneous human combustion," but many of their other pages have real-world impact. For instance, they straightened out a lot of grim hooey about the phony teen-suicide "blue whale game" challenge, and they have provided facts about the Burzynski Clinic, a theoretical treatment for cancer operating out of Houston.

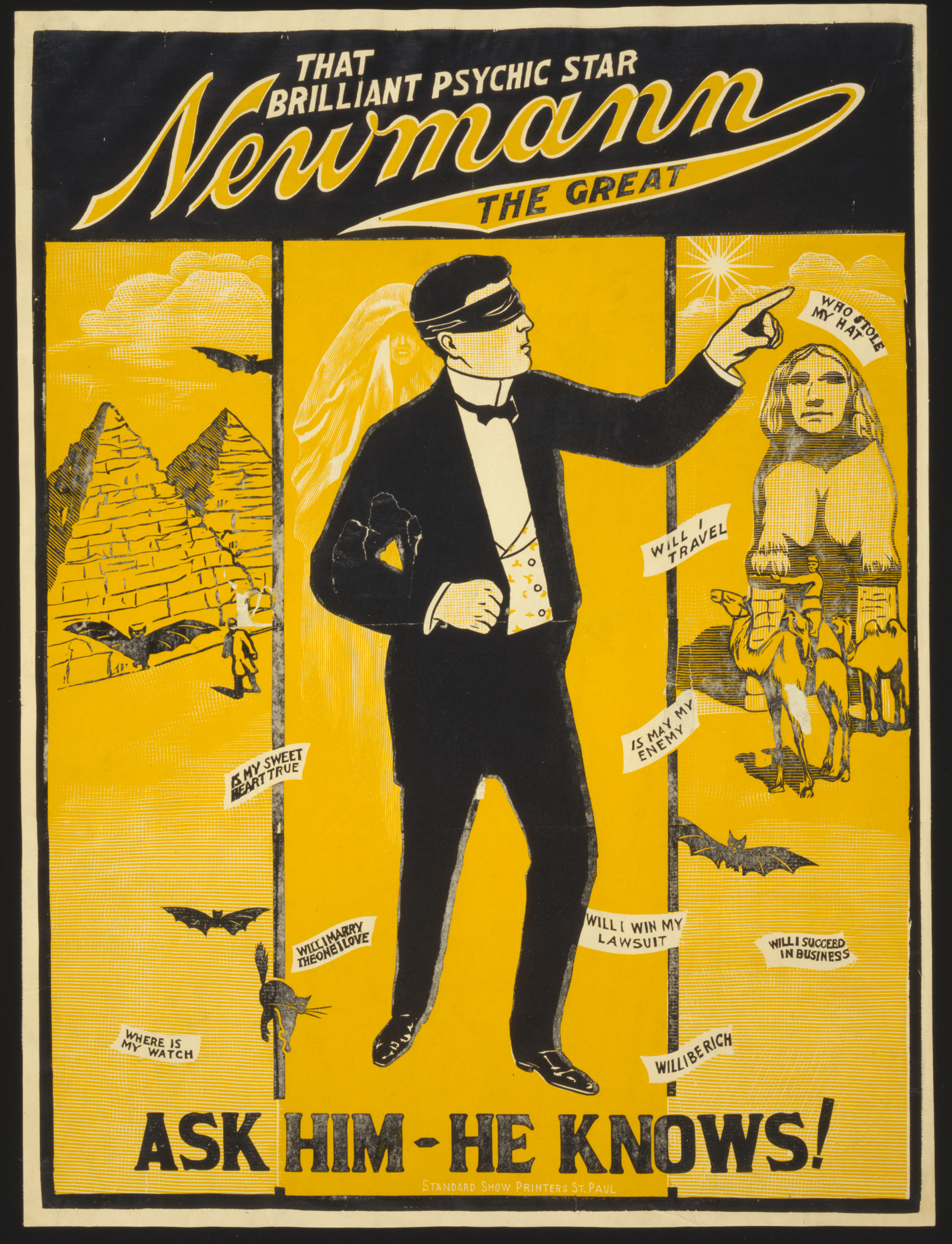

Most recently, Gerbic's members have focused on what they call "grief vampires," the kind of middlebrow psychics who profit by claiming to summon the dead in venues ranging from Motel 6 conference suites to wine vineyards. Lately, technology has changed the business of talking to the dead — a $2 billion industry, according to one market analysis — and created new kinds of openings for psychics to lure customers, but also new ways for skeptics to flip that technology right back at them.

For instance, many psychics still rely on "cold readings," in which the psychic uses clues, like your clothes or subtle body signals, to make educated, but generally vague, guesses about your life and family. But the internet has popularized a new kind of "hot reading," in which the psychics come to their shows prepped with specific details about various members of the audience. One new source of psychic intel is Facebook, which has become a clearinghouse for the kind of personal detail that psychics used to have to really sweat for.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The crew invited to last winter's Skype meeting had been vetted by Gerbic to participate in a mission called "Operation Peach Pit." Matthew Fraser, the target, is a young Long Island psychic who resembles Tom Cruise in the role of an oversharing altar boy. He has been on the circuit for years, has a book under his belt, and works some hotel back room every two or three days. The Guerrilla Skeptics are hoping to catch Fraser on tape spewing intimate Facebook details that are totally false about the person the psychic is addressing. In fact, the details aren't true about anyone, because they will be entirely fabricated.

When the Facebook pages have aged enough to look real, and the target psychic is in a town where some of Gerbic's crew live, she will call upon them to don the undercover identities of these Facebook sock puppets and head out into the corporeal sphere. Mark Edward, a mentalist and magician, collaborates with Gerbic in organizing these sting operations. Once the psychic has been stung, the team will write up an account and then post the evidence — video or sound — onto a website dedicated to a particular debunking mission, which Gerbic gives a memorable name. In future events, other skeptics can simply slip into performances and just leave cards with these odd operation names printed on them.

"That's why I do my stings with names that are ridiculous: Operation Bumblebee, Operation Ice Cream Cone, Operation Pizza Roll," she said. "They're all easy to spell and easy to remember. So even if you throw the card away, you might remember ‘Operation Pizza Roll.'" Then you'll work your way to Gerbic's write-up about the psychic you are about to see and, just maybe, find yourself in a thicket of contradictions so intense, you can escape only by thinking.

Gerbic got into the sting racket because of her mentor, James Randi, the famous skeptic who started his career as a magician, the Amazing Randi. After he began busting paranormal con artists as a hobby, Randi won a MacArthur grant that he leveraged into a variety of different venues, including annual ship cruises filled with skeptics, called the Amazing Adventure. On a 2009 voyage to Mexico, Gerbic met Edward, who was on board as the skeptics' entertainment.

Edward himself claims no powers other than to entertain. He once posed as a clairvoyant and wrote a book about his clandestine life as a medium, Psychic Blues. After they became friends, Gerbic and Edward found themselves griping to each other that skeptics had become too much of a closed group. These groups, Gerbic told me, "always seemed to be bogged down by bureaucracy and rules," and she really wanted "to do something and stop [merely] talking about it."

Gerbic told me that the group's previous hot-read sting — Operation Pizza Roll — worked perfectly back in 2017. She and the other skeptics spent 10 days creating Facebook profiles in advance of celebrity psychic Thomas John's visit to southern Los Angeles. Gerbic used her Facebook sock puppets, "Susanna and Mark Wilson," to register herself and Edward.

John is a well-known figure on the psychic circuit. He names people's pets and dead relatives with breathtaking first-attempt accuracy. He has a thriving practice on Madison Avenue, and his press materials tout a host of Hollywood clients, including Sam Smith, Courteney Cox, and Julianne Moore. On the night of the show, in came Susanna and Mark Wilson, dressed in fancy clothes and toting third-row VIP tickets and unobtrusive recording equipment. Because Susanna's Facebook page mentioned her losing her twin brother, Andrew, to pancreatic cancer, Gerbic arrived clutching a handful of tissues, a tactic she encourages because it sends the psychic the message that you will be an emotional and entertaining reading.

Right away, Thomas John said he was tuning in to a twin brother who wanted to speak to his sister. Gerbic raised her hand. Over the course of the reading, John comfortably laid down the specifics of Susanna Wilson's life. He knew that she and her twin brother, "Andy," grew up in Michigan and that his girlfriend was Maria. He knew about Susanna's father-in-law and how he died.

When I reached Thomas John, he insisted he did not use Facebook and explained away the incident. "I have my eyes closed for an hour and a half when I'm doing readings," he said, "If she spoke up during that period of time, I don't remember that. It's possible." Since the sting, John used his prestige out West to launch Seatbelt Psychic, a show on Lifetime in which he "surprises unsuspecting ride-share passengers" when he "reveals he can communicate with the dead."

By March of last year, the new fake Facebook pages were up and running, and they were fantastic — credible fictional characters built out of regular posts. I met "Zoe" and "Ed" on a cold winter morning in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania, at the home of Donna and Kenny Biddle. They were getting into character. Three other new friends were there, and they were also in their characters. The five of them were chattering nervously, excited to be heading out on a real mission.

The Valley Forge Casino in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, is one of those modern revenue-enhancement ecosystems whose carpets ease the crushing of your soul with faded earth colors. Down a football-field length of sterile corridors is a conference room with a poster outside of a beaming Matthew Fraser.

To open his show, Fraser deployed some self-deprecating jokes, salted with some spicy obscenities, warming up the crowd. The audience was sizable and mostly women; the few disgruntled husbands in the crowd wore the faces of men who had been blackmailed. Zoe and Ed and the other Guerrillas sat near the front in hopes of being noticed. I sat alone, about four rows behind them.

Fraser walked down the aisle and straight to my row. Right off, he said he had a vision and asked the dozen or so of us to stand. The crowd was older, and without much trouble, Fraser easily divined the very likely fact that someone's mother on the row had passed. He quickly identified a woman near me and handed her a microphone. "Your mom is acknowledging that, 'I have to speak to my daughter,'" he said, and then let the woman know that Mom was okay in the afterlife. "Your mother says that she wants you to know that she loves and cares about you."

It was a classic cold reading, all generalized notions searching for something slightly more specific to move to. Fraser often nodded his head as if to nudge her to go along. "Your mom tells me that she was angry before she left this world, and you don't want to talk about that." Fraser stepped back, held her gaze and encouraged her, "You understand that?" She agreed. As he teased the story along, Fraser might, oddly, crack a joke to ease the tension but then take the room right back to this quiet place. Fraser said, "'I need to apologize to my daughter because every day she deals with the stress and the burdens.'"

Suddenly, the real sorrow of this stranger's loss was here, near me, on my row. And then the whole room felt it. "Your mom says, 'I am taking responsibility for that.'" I could barely look up. This little moment felt so intimate and private. Grief is one of those emotions that doesn't happen publicly too often, and so when it does, the mood easily dominates the room. With each reading, Fraser was, in fact, summoning the dead, because all these middle-aged people had lived lives. We all knew death, family death, deeply felt. One by one, everyone in the room was reliving some loss. Helplessly, I thought of my own father, who died when I was 11, and those old emotions, stored away but never far off, took hold of me as if I were graveside.

By the time Fraser inched his way to the other side of the auditorium, people were even more forthcoming. Fraser came to a middle-aged woman dressed in a colorful scenic sweater. Her burly husband with a snow-white goatee and veteran's cap was beside her as she revealed losing two of her sons in tragic ways. She said she missed them every day.

The audience was with her; our grief held her. We were all wrapped in rich, old memories of aching pain. Maybe dead spirits aren't real. But these emotions were. My exhausted father waking up early on his Saturday off to watch cartoons with his little kid. Decades disappeared. I squeezed back a little boy's confused tears. "Sonny boy," my mom said one morning, "I have something sad to tell you." I so miss him.

Fraser consoled the mother with news. "Your son says he's okay," Fraser said, speaking in the voice of one of her deceased boys. The mother sobbed and sank into her husband's big chest. "More important, they are together on the other side." Fraser learned that Christmas was no longer celebrated at home, and Fraser crushed the room: "He says you have another son who needs you?" The husband nodded; she nodded. "He says to me, 'Just because we've passed, it doesn't mean my mother stops her life.'"

Even the most stoic of men were overwhelmed, heads turned away, into shirt sleeves. Fraser stepped toward the couple and took both of them in a long, sobbing group hug. Then he moved away.

There were a few more readings, each a little bit easier emotionally. Fraser was a brilliant performer, cooling off the room. With a couple of light jokes salted with naughty words, he bolted onto the stage, and then disappeared into the wings.

Eventually, Gerbic's Guerrillas will produce an account, and Operation Peach Pit will be online with the hope of reaching a future audience with logic. But there was no denying the real power of what we all felt in the room.

-

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interview

Colbert, CBS spar over FCC and Talarico interviewSpeed Read The late night host said CBS pulled his interview with Democratic Texas state representative James Talarico over new FCC rules about political interviews

-

The Week contest: AI bellyaching

The Week contest: AI bellyachingPuzzles and Quizzes

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more