Superheroes, they're just like us

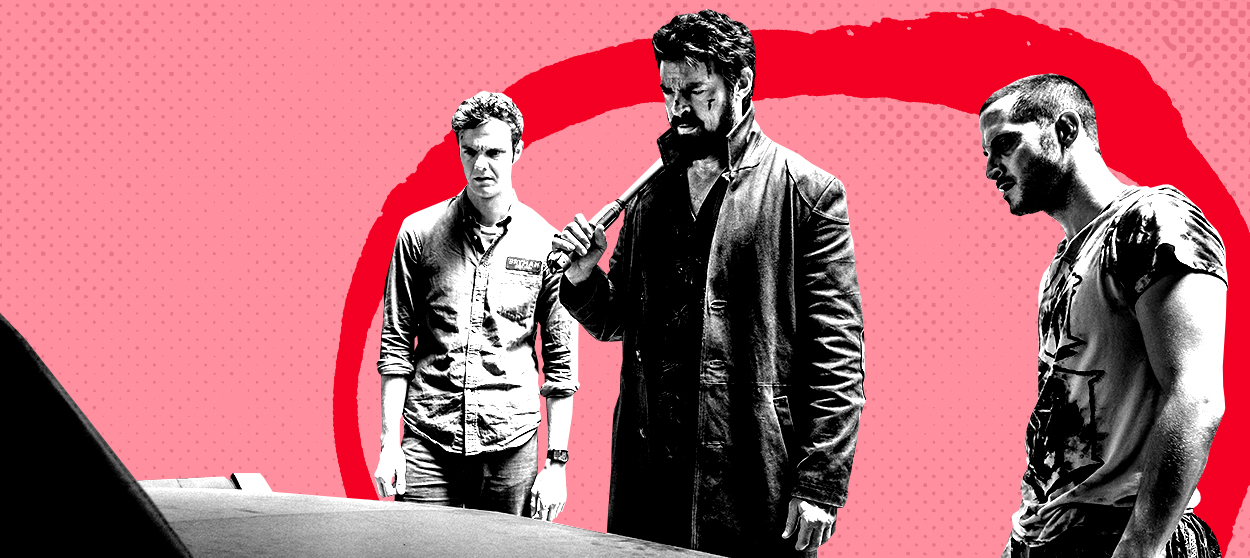

Does Amazon's The Boys have anything freshly subversive to say about the comic-book genre?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

So far, when I've ventured the opinion that Eric Kripke's Amazon Prime adaptation of The Boys is actually a pretty good show, people who know the original source comics have expressed doubt and surprise. They're right to be dubious. If you look back at the comic book run that Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson began in 2006 — about a world where corporate-sponsored superheroes are actually sexually-depraved egomaniacs who have to be exposed and taken down by a specially formulated (and super-powered) CIA squad — it's easy to understand why Kripke had to change so much of it. A more faithful adaptation of the material would probably have been awful. The original comics are peak-2006, not only drenched in pornographic sadism and sexual violence — shocking the audience for the sake of shock itself — but also coasting on what they think is a novel premise: in a world where superheroes are sexually-dissolute hedonists, the good guys are actually — and this will blow your mind, so strap yourself in — bad.

Even then, it was far from the first time that comics had played with the idea of sexually-deviant superheroes expressing their super-fetishes through super-violence. But the "gritty reboot" hadn't yet become such a stale cliché. Christopher Nolan's grimdark Batman had begun to supplant the dayglo cartoonishness of the character's previous film incarnations (going deeper into the Frank Miller and Alan Moore version of the character that Tim Burton had deployed in the 1989 Batman), but the now-hegemonic DC and Marvel cinematic franchises were still just a glint in Hollywood's eye. The prestige "anti-hero" show was also still relatively new: Tony Soprano was still on the air — and a point of reference for the comic, along with other fresh new voices like Quentin Tarantino — but no one had yet heard of Walter White, and Game of Thrones, whose "realistic" depictions of sadistic sexual violence would launch a thousand think-pieces, was still just a series of fantasy novels that the world still believed George R. R. Martin would someday finish.

In 2006, in other words, "shocking" the audience with sexual violence could still be plausibly argued to be interesting. There was even still some frisson in suggesting that America might be bad: after a decade of ‘90s triumphalism and post-9/11 pieties, using hyperviolent and corrupt superheroes to suggest that "the world's only superpower" was actually a stupid, corrupt, and hedonistic monster could still have some bite.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(In Donald Trump's America, perhaps, not so much?)

What's most surprising about the 2019 adaptation, as it turns out, is that nothing in it is very shocking. This might be, in part, because our tolerance for — and expectation of — pop cultural violence has grown; if the show had aired as it is in 2006, the blood-splattering bodies and gruesomely-portrayed sexual harassment probably would still have been shocking. But "shock" is also not what Kripke and company are going for. If the comics giggled at the uncensored violence of what superheroes would really be like — and had sadistic fun suggesting that this reality would be gory, spectacular, and pornographic — the adaptation has a much more deeply depressing vision: a world with superheroes, it turns out, would be exactly like our own.

As in the comics, The Boys begins when the protagonist's girlfriend is accidentally killed by a drug-addled superhero — whose handlers and PR team immediately try to pay him off to hush it up — and the protagonist, Hughie, is invited to join a team of anti-superhero vigilantes, all apparently motivated by vengeance. In a parallel plot, the biggest celebrity superhero team "The Seven" welcomes a new member, the innocent heartland girl-next-door "Starlight"; she is almost immediately coerced into sex by a co-worker, in a manner for which the adjective "Weinstein-ian" is horribly appropriate. Over the course of the season, their stories run in parallel: while Hughie — a former superhero fan — learns the truth about the dark underbelly of superhero society, Starlight's disillusionment happens from within the beast itself. As they work to save each other, they also, unsurprisingly, converge in a somewhat predictable romance plot.

So far, so good: a stripped-down version of things that happen in the comic books. But instead of cranking up the spectacle, the adaptation brings it down to earth. If it's horrible when Hughie witnesses his girlfriend's body explode — after a super-fast superhero accidentally runs through her — it is exactly and precisely as horrible when, in the next episode, Hughie uses extremely conventional explosives to blow up a (different) superhero. Does it matter that his girlfriend was run over by a drug-addled celebrity superhero, rather than, say, a coke-addled celebrity driving a car? By the same token, when Starlight is sexually abused at her new job — in a scene which, unlike the extremely upsetting comic book version, mostly happens offscreen and by implication — nothing about it is significantly different than the forms of sexual violence and coercion which are endemic to so many "normal" workplaces. That it's a superhero coercing another superhero doesn't change the power dynamics, nor does the subsequent (corporate-orchestrated) coverup and PR campaign — when she eventually goes public — differ very much from how "Me Too" revelations are handled in Hollywood today.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

To a point, you could say that the show's superheroes function as a satire of contemporary celebrity culture: beloved and admired by all, they turn out to mostly be highly-paid but spiritually-broken depressives. The damage they do is real, of course, and the show's version of Superman — a creepily evangelical, flag-bedecked sociopath named "Homelander" — is actually quite scary. But they're not very interesting, or at least not as superheroes. Their problems are boringly identical to the problems of the analogous celebrity types: the fact that "A-Train" has super speed, for example, doesn't make his story very different than that of any other aging athlete struggling with performance-enhancing drugs and younger competitors. In that sense, they aren't satires of or metaphors for celebrity at all; they simply are celebrities.

In that sense, the most interesting choice the show makes is to portray superpowers as not very important or useful in modern society, except as media spectacle. The crimes they occasionally deign to stop are all intensively researched, planned, staged, and then recorded by the Vought Corporation, but only to produce reality television for a corporate-controlled pop cultural empire of shows, movies, comic books, costumes, and toys from which everyone profits; the business of superheroes is mostly just business. In this sense, it flawlessly replicates the superhero industry we have in our world; the fact that superpowers are real changes nothing about it. What would be different about a world where Robert Downey Jr. really was Iron Man or Gal Gadot really was Wonder Woman? Nothing, it turns out. The subversive suggestion is that the mass media, the capitalist economy, and the military industrial security complex are so vast and complete that real superheroes are essentially superfluous, a curiosity.

It makes logical sense. After all, in the absence of supervillains, what "crime fighting" could a superhero do that couldn't be done just as easily (and with less destruction) by normal-powered police officers? Police and military already have at least as much "power" as they could plausibly need (and arguably much more than they should). For the same reason we don't arm police officers with tanks and missile launchers, super-powered efforts to "save the day" tend to produce horrific body counts (as in an ill-fated effort to stop a transatlantic plane hijacking). The Pentagon has good reasons for wanting nothing to do with them and the CIA regards superheroes with very well-founded suspicion. And so, while much of the season hinges on the Vought Corporation's plot to get what Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman already have — profitable government contracts — what's most striking about their evil scheme is how limited its ambition is, and how banal. All anyone can think to do with their superpowers is make money, and all of them are pretty universally lonely and unhappy. It makes you wonder — as many of the superheroes themselves do — why anyone would want to be a superhero in the first place.

It's a surprisingly good show, much deeper and more well done — and fundamentally humane — than one would have reason to expect. And yet for all its cynicism, The Boys comes at a moment of true superhero saturation, when even the most successful franchises are struggling to be "about" anything but themselves. Does the world need yet another story about superheroes that subverts the idea of superheroes? What's left to subvert? The 2006 comic's ultraviolence might have seemed as fresh and subversive as Kill Bill did, back then, but in 2019, a superhero show about superheroes might be as superfluously self-indulgent as Quentin Tarantino making a movie about how much Quentin Tarantino likes movies. It's a media spectacle about a corporation using media spectacle to become a military contractor; that it's made by Amazon — a corporation that makes movies and contracts with the military — doesn't make that irony any more meaningful.

If superheroes are little more than superfluous parasites on the attention of an adoring public (but ultimately empty and sad, and not all that deep), then the show makes a good argument that you don't need to watch this show. But if The Boys does have something fresh to say, it's not about superheroes or celebrity or even about media. It's about the things that we use power fantasies and spectacle to distract ourselves from, and to forget. Every superhero has an origin story, and in most conventional superhero stories, those origins — which are usually the traumatic loss of family members or friends — give the superhero their powers. The greater the tragedy, the greater the power. But while a nesting series of revenge plots sets the season in motion — men seeking vengeance against the men who have brutalized "their" women, a rehearsal of the oldest and most in-need-of-being-retired superhero cliche — the final revelation (and most interesting alteration of the source material) is that almost every origin stories is a lie, self-interesting evasions of more uncomfortably banal truths. Villainy usually turns out to be pathos, abuse that's become cyclical, or the lie that a grief-stricken would-be hero tells himself to avoid looking inward. Revenge is as pointless, it turns out — and as much of a self-indulgent distraction from the things that really matter — as superheroes themselves.

Aaron Bady is a founding editor at Popula. He was an editor at The New Inquiry and his writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New Republic, The Nation, Pacific Standard, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. He lives in Oakland, California.