What a suspicious pattern of Trump trades really reveals

Be very skeptical of an article suggesting Trump is trading off his own foreign policy. But also be very skeptical of futures markets.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Is the Trump presidency ultimately just a scam to make the Trump family money?

Allegations to that effect have been made almost continuously since Trump took office — and are frequently indisputable. From his expectation that foreign visitors will stay at Trump's Washington hotel to his recent decision to host the entire G7 at his Florida golf resort, the petty corruption of this administration has been taking place in plain sight. Sadly, these stories have had only limited political impact.

But what if Trump is engaged in corruption on a much vaster scale, using the power of the presidency to move markets, and trading in advance on the expectation of those moves? That's the possibility raised by a recent article by William Cohan in Vanity Fair about whether someone is profiting from advance knowledge of Trump's market-moving statements — to the tune of billions.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here's the most potent example of suspicious trading:

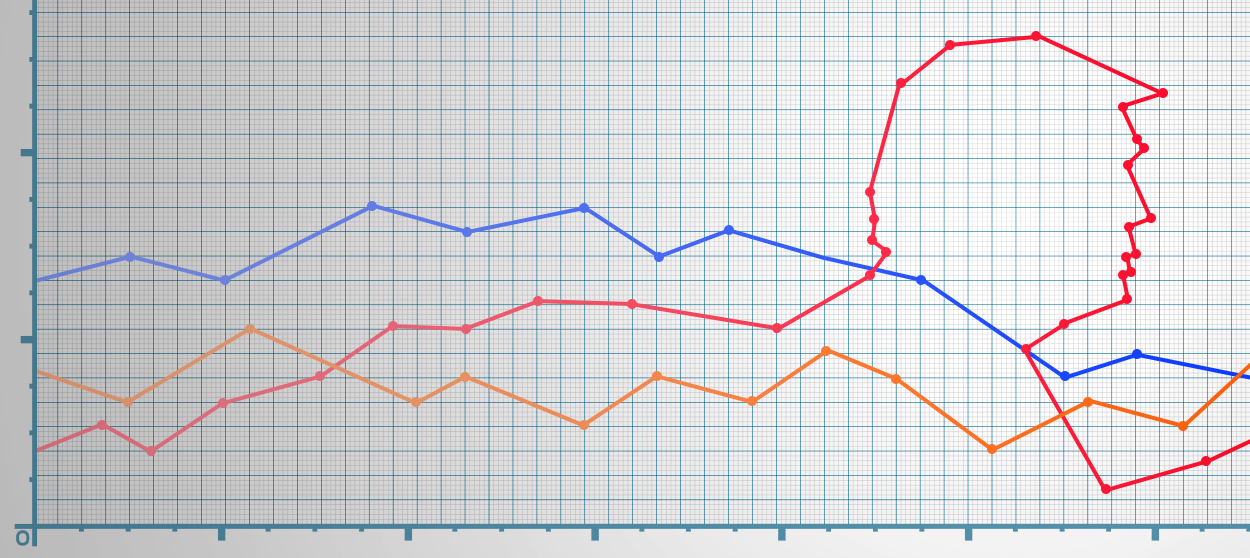

[A] trader, or group of traders ... bought 420,000 September e-minis [the most popular future's contract linked to the S&P 500 stocks index] in the last 30 minutes of trading on June 28. That was some 40 percent of the day's trading volume in September e-minis — making it a trade that could not easily be ignored. By then, President Trump was already in Osaka, Japan — 14 hours ahead of Chicago — and on his way to a roughly hour-long meeting with China's President Xi Jinping as part of the G20 summit. On Saturday in Osaka, after the market had closed in Chicago, Trump emerged from his meeting with Xi and announced that the intermittent trade talks were "back on track." The following week was a good one in the stock market, thanks to the Trump announcement. On Thursday, June 27, the S&P 500 index stood at about 2915; a week or so later, it was just below 3000, a gain of 84 points, or $4,200 per e-mini contract. Whoever bought the 420,000 e-minis on June 28 had made a handsome profit of nearly $1.8 billion. [Vanity Fair]

The timeline is indeed suggestive — but consider what the suggestion implies. The trader in question would have to have known in advance not only what Trump planned to say in the meeting, but that after the meeting he would be able to trumpet success (however temporary). Moreover, to hold the trade for a week and realize that entire profit, the trader would need to know that any subsequent bad news — such as Chinese officials pouring cold water on happy talk, which is what happened in August in another example cited in the article — would be delayed for several days.

How could any trader possibly know that much? Knowledge of that scope implies not only inside information, but coordination at the highest level. That's precisely what makes the allegations so alarming. But it's also what makes them highly questionable.

Consider further that several of the examples cited in the article are instances in which any insider information would have to have been obtained not from Trump but from foreign governments. Cohan reports that a large volume of e-mini futures were traded just before closing on September 13, a few hours before the drone attacks on Saudi oil infrastructure. Similarly large trades took place a few hours before the Chinese government announced the lifting of certain tariffs, and also just before Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced the withdrawal of the extradition bill that sparked widespread protests in the city. How would Trump, or a crony of his, know any of that? It is just barely possible, if extremely unlikely, that someone connected with the Trump administration had advance knowledge of announcements by the Chinese government. But the notion that anyone knew in advance about the attacks in Saudi Arabia takes us into 9/11 "truther" territory.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What looks like a suspicious pattern of activity to an outsider might actually be completely innocuous. As a debunking story in Slate by Felix Salmon points out, the original Vanity Fair piece does not clarify whether the trades in question are abnormally large, nor whether the positions were held long enough to make the extraordinary profits Cohan suspects were earned. All he really has is the feeling on the part of some traders on the floor that the size and timing of the trades look suspicious.

Does that mean there's nothing to see here? On the contrary — it suggests there might be quite a bit more to see than just malfeasance by a Trump crony. Indeed, if there is a systemic problem in the futures market, where the connected can profit easily from advance information about political events, it would be shocking if Trump were the innovator in anything but sheer brazenness. Surely Russian oligarchs, Chinese billionaires, Saudi princelings, and American hedge fund operators would have gotten there first. If Cohan's suspicious traders are right, they may have. But it would be difficult to know, precisely because futures markets are not set up for the kind of transparency that characterizes the stock market.

The concept of insider trading is a difficult one as such, inasmuch as the only ways to make money by trading in the market are by luck or through an information advantage: knowing something that other people don't know. The prohibition on insider trading is not intended to prohibit profiting from such an information advantage, but to insure that any such advantage is not obtained in a corrupt manner. It's relatively straightforward to identify the kind of privileged information that can move an individual stock, but it's far harder in the futures market, as commodities and stock indices are moved by such a wide variety of macroeconomic factors. Indeed, until fairly recently the CFTC did not even have a task force assigned to investigate cases of trading on misappropriated information. And yet, the combination of depth, liquidity, leverage, and opacity makes the futures markets ideal venues for gargantuan-scale profits, for anyone who truly has advance knowledge of market-moving information.

Are corrupt information advantages an important factor in today's futures markets? If they are, and that isn't addressed, then not only could investors at large be defrauded of billions, but confidence in the financial markets would decline, with serious economic consequences. That's ultimately why insider trading is so damaging: not only because some individuals profit unfairly, but because the expectation of that behavior turns outsiders away from the markets, turning the economy as a whole into ever more of an insider's game.

But even if Cohan's article is bogus, if suspicions of this kind of corruption are actually widespread, that itself could have a negative impact on market confidence. Assuring that confidence depends on having credible regulators, transparency about market transactions — and a press that takes its own responsibility for accuracy more seriously than the quest for clicks.

It's surely worth investigating whether anyone in Trumpland was involved in such trading. But the bigger challenge is to restore and preserve confidence in the system. As is so often the case in the age of Trump, the big picture story isn't only about Trump's corruption, but how Trump's vastly more brazen behavior has exposed the extent of the rot that preceded him.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The week’s best photos

The week’s best photosIn Pictures An explosive meal, a carnival of joy, and more