John Bolton and our collective yearning for justice

The Room Where It Happened is a throwback to a more innocent age

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was a wild week in politics, and all because of a book. The blistering nonfiction account, written by a morally dubious figure with months of White House access, portrayed President Trump as a venal lout with a toddler's grasp of the world. Early excerpts revealed that a publicly loyal official disparaged Trump behind his back, and alleged that the president had engaged in acts that were, if not impeachable, deeply troubling. Trump and his allies reacted with a barrage of angry tweets, dismissive statements, and sternly-worded legal threats. Unsurprisingly, the book hit number one on Amazon before it was even available.

Yes, the days surrounding the publication of Michael Wolff's Fire and Fury, in January 2018, were memorably hectic, with turncoats revealed and allegations — such as the author's claim that "100 percent of the people" in Trump's orbit considered him unfit — leveled. On the day it was released, Trump called the book "Full of lies, misrepresentations and sources that don't exist" and later declared Wolff "a total loser." The cycle was soon repeated with Bob Woodward's Fear (which Trump called "a con on the public"), Andrew McCabe's The Threat ("a puppet for Leakin' James Comey"), and Omarosa Manigault Newman's Unhinged ("Good work by General Kelly for quickly firing that dog!"). There were books by Comey, former aide Cliff Sims, and an anonymous administration official. All painted damning portraits of Trump, and all were bestsellers. None had any effect on the president's political fortunes.

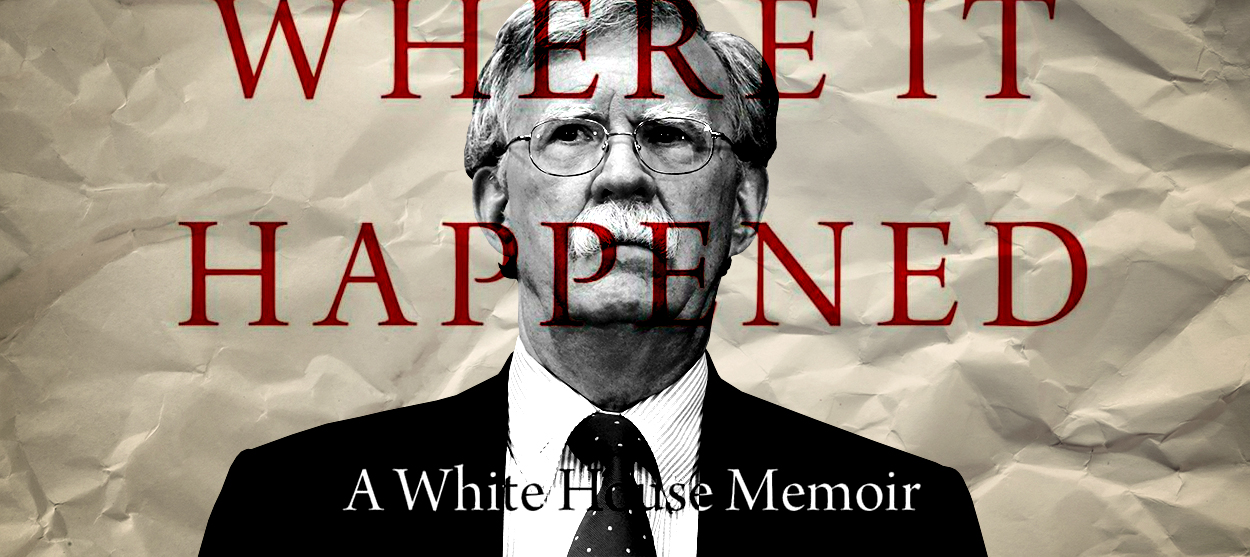

The latest addition to the shelf is John Bolton's The Room Where It Happened: A White House Memoir. Bolton, who resigned as Trump's national security adviser in September, alleges that the president begged China to help with his re-election, thought Finland might be part of Russia, and wants journalists to be killed. Though the Justice Department is trying to block the book's publication on national security grounds — and seize the $2 million that Bolton reportedly received for it — it seems likely that on Tuesday, hundreds of thousands of people will be reading it for themselves.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Despite the gravity of Bolton's charges, there's a throwback naivete to how everyone — from the public to the media to the president himself — is responding to his memoir. Its leaked details have been breathlessly reported (in a typical front-page analysis, The New York Times tells us that "an 'erratic,' 'impulsive' and 'stunningly uninformed' Mr. Trump could make 'irrational' decisions"). Trump, dutifully playing his part, this week called Bolton a "wacko" and a "sick puppy," and said that the book "is getting terrible reviews." Bad reviews notwithstanding, readers, caught in the maelstrom, are lining up for it. "John Bolton's damning indictment of the Trump presidency is soaring up online charts," The Guardian writes. It has "knocked anti-racism titles by authors including Ibram X Kendi, Ijeoma Oluo, and Robin DiAngelo off the top spots."

Fire and Fury, the first of the genre, was initially seen as a legitimate danger to Trump; just 12 months into his term, we thought that a book could damage him. We were so young. "It takes a thief to catch a thief," wrote The Los Angeles Times, "and Michael Wolff ... is the ideal hustler to capture President Trump." Wolff told the BBC that Fire and Fury was creating "the perception and the understanding that will finally end ... this presidency." And though it caused a rift between Trump and "Sloppy Steve" Bannon, the strategist who supplied its harshest details, there was no wider fallout; the thief slipped away unscathed. Trump's job approval rating two days after Fire and Fury's publication stood at 37 percent; one month later, it was up 3 percentage points.

If it seems inexact to use a metric like job approval to judge such a book's success, we should ask ourselves what we expect these books to do, and why we read them at all. Forty-two months and countless exposés into Trump's presidency, we now understand that The Room Where It Happened is unlikely to move the needle. As my colleague Windsor Mann recently put it, "In terms of effecting political change, Bolton's book will be as inconsequential as the United Nations resolutions he made a career out of deploring." And why wouldn't it be? Impeachment, the dread "nuclear option," proved to be a quixotic failure; no matter what Trump might have said to Chinese President Xi Jinping about soybeans, the Senate will not remove him from office for it. So why do we care so much?

For 200 years or so, an informal system of political punishment served America reasonably well. If an official was found to have done something untoward — sanctioning bribery, bugging an opponent's campaign headquarters, posing for a photo with a model on his lap — there would be repercussions; voters would be forced to reappraise the offender in light of what he or she had done. If you were Warren Harding or Richard Nixon or Gary Hart — people who strove to present themselves to their supporters as virtuous — your name would be stained, and your career would likely cease.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But as we all know, Trump plays a different game. Instead of virtue, he preaches a seething, primal badassery, so his offenses never surprise. He has been credibly accused of bribery, campaign meddling, and philandering — Harding, Nixon, and Hart in one convenient package — and each time, he has survived. Yet whenever a book like Fear or The Room Where It Happened is announced, the public rushes towards it — not because we think it'll make a difference anymore, but because it might have in the past. For all the chaos of recent years, we still yearn for justice. There must be consequences, we hope with our weary, Trump-addled brains. Maybe these truths will do what truths are supposed to do.

It is the poignant self-delusion of a country — or at least half of it — that, three and a half years in, still cannot accept its fate. We'll cling to any scrap of truth — even if it comes from John Bolton, who Democrats have long regarded as a vile warmonger. It's a childish belief in some benevolent, balancing force. And though we might rationally know that no such force exists, our politics are profoundly irrational.

So we'll buy Bolton's book and shake our heads at the things he says happened in that room. And when we're done, we'll put it on the shelf, let out a little sigh, and wait for the next one to arrive.

Jacob Lambert is the art director of TheWeek.com. He was previously an editor at MAD magazine, and has written and illustrated for The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia Weekly, and The Millions.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day