The harm reduction phase of the pandemic

Right or wrong, people are fed up with lockdowns. So how do we best protect public health going forward?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This past week, as I was leaving a newly re-opened restaurant, where wait staff wore masks and half the tables were marked for disuse to ensure distance between patrons, I saw an older man with a disposable mask wrapped around his upper arm. "They said I have to wear it," I overheard him say. "They didn't say where!"

This is the attitude a significant minority of Americans now hold toward public health measures intended to curb the spread of COVID-19: They are nonsense to be flouted, and they were nonsense — perhaps intentionally totalitarian nonsense — from the start. That perception of vindication and the behavior it produces, like wearing your mask on your bicep, is why we've reached what should be the harm reduction phase of the pandemic.

There was always skepticism of coronavirus containment recommendations, but for many pandemic skeptics, vindication has come from an unexpected source: the very public health experts (and the journalists amplifying their message) they'd dismissed as power-hungry manipulators. The play, in the skeptics' narration, has four acts:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

1. The lockdowns and other social distancing rules, with public health experts insisting these were necessary to save lives.

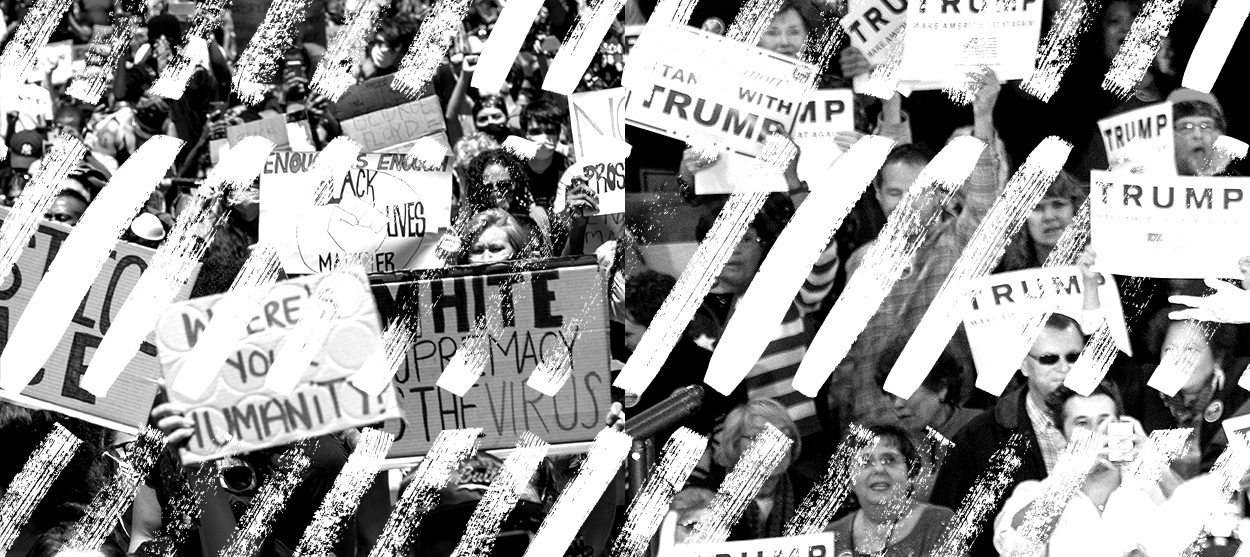

2. The small, few lockdown protests, which some public health experts and journalists (including me) worried could become superspreader events if COVID-19 was as contagious as some studies suggested.

3. The large, numerous protests of police brutality and racial inequality, to which some public health experts responded by issuing very mild warnings heavily glossed with approval of the demonstrations.

4. President Trump's rally in Tulsa this weekend, which already has been heavily covered as a potential superspreader event, once again with dire warnings from some public health experts and journalists.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Reality, of course, is not this neat. Trump's rally is indoors, and most protests were outside. Moreover, the public health experts who decided protesting police brutality is worth the risk of contagion are not necessarily the same experts now warning against the rally in Tulsa. Chief pandemic adviser Dr. Anthony Fauci said Tuesday he "of course" would not attend the rally because of the risk, but Fauci was also "very concerned" about the policing protests, which he called "the perfect setup for the spread of the virus."

When we think of "public health experts" as a single entity which has shamelessly contradicted itself, we aren't thinking rightly. Some public health experts did flip-flop, giving unadmitted priority to their political opinions over their professional expertise. Others didn't. Some changed their minds about the nature of the risk between January and June as better information became available and updated their advice accordingly. Others gave different advice because conditions changed: Testing and hospital capacity expanded; mask use increased; and the virus may well be seasonal, making outdoor assembly in warm weather very low risk.

Regardless of such qualifications, the perception of a brazen reversal is widespread, and it isn't groundless. Public health messaging in aggregate changed considerably, and part of that change was politics. Criticism of Trump's Tulsa rally from that same aggregate will be the final confirmation for those already inclined to doubt public health expertise. The pandemic response, these playwrights conclude, was nothing but politicking.

Unfortunately, that aggregate messaging shift can't be undone. Minds are made up. Masks are on arms. And though it hopefully will not reach the dire situation we saw in New York City, a pandemic resurgence seems to be underway in some states, including some with earlier re-openings and laxer current guidelines. Meanwhile, just past the three-week mark since policing protests began, we have yet to see big spikes in cities with the largest demonstrations. But Houston seems like a possible exception to that trend; Los Angeles too has rising cases; and other protest-prompted spikes could still be coming, especially if young, asymptomatic protesters are infecting higher risk family and friends.

I suspect the best option now is a harm reduction approach, a public health concept more often found in contexts of drug addiction. Harm reduction is a realist model concerned with reducing negative consequences when harmful choices cannot be entirely prevented. Needle exchange programs may be the most familiar example.

For COVID-19, we are past the point of "abstinence," to extend the drug use analogy. There's been talk of rolling lockdowns as infections spike and drop, but I struggle to envision widespread compliance with another lockdown after a summer of huge protests. Even the non-skeptical are deeply weary of isolation, and COVID-19 skeptics will do what they want. Officials must recognize there is probably no way to change that without enforcement measures far more draconian and legally questionable than we've seen already. Lockdown is functionally done. No one is going to stop using.

So what's the equivalent of providing clean needles in the fight against COVID-19? As economist Emily Oster explained at The Atlantic before the protests began, it means helping people understand "the next-best alternative" to the public health ideal, "communicat[ing] a range of risks, and [speaking] in terms of probabilities rather than in binaries."

Harm reduction for COVID-19 means if people won't stay home, make it easier for them to get tested as often as needed. If religious communities are determined to meet in person, let them do it in large sanctuaries instead of forcing them to conceal their gathering in far smaller and riskier private homes. If the choice is between opening public pools and having kids from multiple households crowd around the TV all summer, open the pool. And practice the honesty that was too neglected in the conversation about the policing protests: Recognize that there can be competing goods, and that doing the best we realistically can is better than doing nothing at all.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney