Coronavirus has an optics issue

This is one of the darkest moments of American history. Why doesn't it feel like it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The United States — a country that, in the last 80 years, has experienced an enemy strike on its soil, a presidential assassination, and a terrorist attack in its largest city — is entering the "darkest winter in modern history," in the words of one whistleblower. An American now dies roughly every 30 seconds of COVID-19, meaning that by the time you finish this article, 14 or 15 more people will be dead. The virus, which has been in the U.S. for less than a year, passed heart disease last week as the leading cause of death. And yet "we have not even come close to the peak," Dr. Michael Osterholm, the director of the Center of Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, recently told CNBC.

So why does everything feel so … normal? Or perhaps not normal, but at least the same. We are only on the cusp of what experts say will be the hardest three or four months in living memory for our country, but for many it seems increasingly difficult to muster genuine concern — at least if the pandemic has not touched you or your immediate loved ones directly and significantly. Part of that is due to compassion fatigue, as well as the general mental drain from every day of the last 10 months being a crisis. But the pandemic also has an optics problem, one where the lack of emotional images is leading to an easy dismissal by the remaining, yet-untouched public.

When the outbreak first began, we were overwhelmed with images: the spiky medical illustrations of the crown-like virus, designed to elicit a "feeling of alarm"; graphs with multi-tentacled arms showing the U.S. shooting ahead of China and Italy in cases; field hospitals and mass graves in New York City; and, most strikingly, photos of "the great empty," the abandoned landmarks of the world during lockdown. But what was lacking was a face. Though the images were exciting or shocking or scary, they focused primarily on health-care workers or other quiet, empty images of the "new normal." Nearly a year on, it's telling that there is still no "Napalm Girl" of the COVID-19 crisis.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But it is such images that "force us to contend with the unspeakable," The New York Times' Sarah Elizabeth Lewis wrote in May, in an opinion piece asking, "Where are the photos of people dying of COVID?" Pictures, Lewis further argues, "help humanize clinical statistics, to make them comprehensible." Think of Vietnam, where photojournalists brought the grisly realities of war into Americans' homes, and then later, the contrasting, sanitized images out of Iraq and Afghanistan, after the government learned its lesson and restricted photographers to "the highly controlled system of embedding," in the words of Mother Jones — down to even a ban on photographing soldiers' coffins. Photos are powerful tools, after all, and even more so when they have a central character we can connect and empathize with; such pictures have, over the decades, swayed distant people living safe and stable lives into caring about famine in South Sudan, the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean, the Dust Bowl refugees, and even the American Civil War.

The COVID-19 crisis is not distant. And yet, there is no enemy to photograph, beyond digital reproductions of the virus. More importantly, there are no central characters. Interchangeable health-care workers in hazmat suits or hospital gowns remain unidentifiable behind their protective equipment; masks, further, make it nearly impossible to read stress into a doctor's expression, or grief into a mourning family's eyes. When the dead are brought out of hospitals, they're anonymized by body bags, their final horrifying moments going unimagined. The images the COVID-19 pandemic is producing are dystopic curiosities; many are staggering. But they lack the searing, messy, emotional pull that might allow for the 46 percent of people who don't know someone who's been hospitalized or died of COVID-19 a window into the understanding of the pain of those who are on the front lines.

As Lewis points out in her article for the Times, some of this optic disconnect and alienation is due to America's medical privacy laws; also ethical questions about photographing dying or dead patients. Access is also an issue, since many COVID wards are so tightly restricted that even family members are not allowed in. But the result is that we can't process headlines like "280,000 people dead," unable, as we are, to know what it looks like to die on a ventilator or of renal failure. Health-care workers might beg us to take the pandemic seriously with upsetting testimonies, but unless we're working in a hospital ourselves, there's no concrete vision of what these pleas actually mean. Even documentaries about the pandemic — like 76 Days, which follows the outbreak in the epicenter of Wuhan, China — struggle to pick out firm characters, hidden, as they are, behind either the PPE of medical staff, or the tangle of tubes and respirators of the dying.

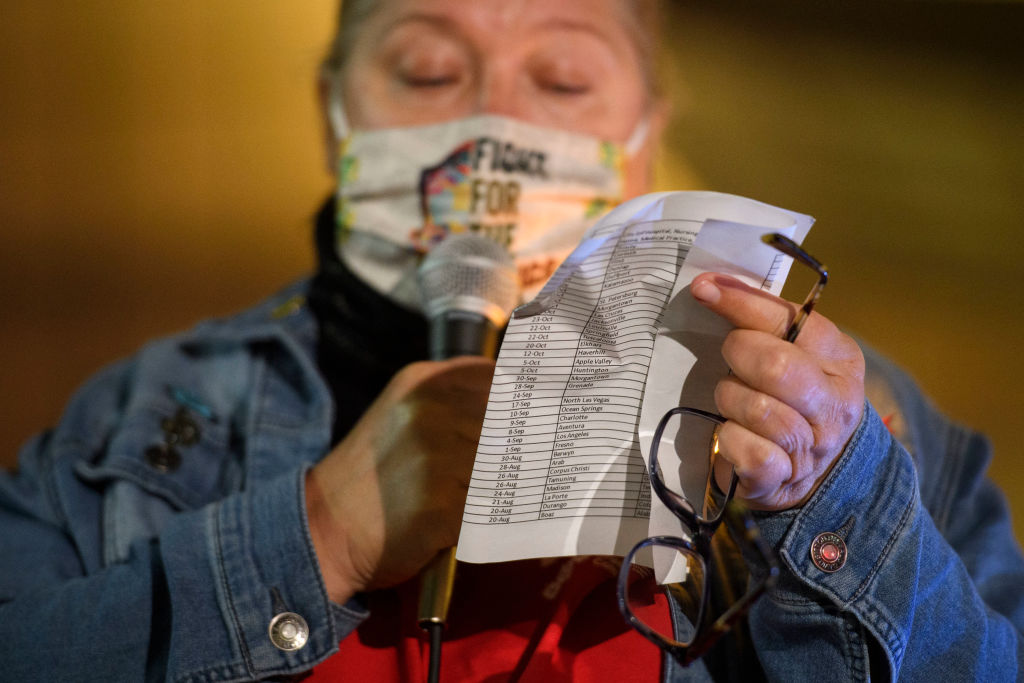

What, then, is there to do? We should treat COVID-19 like the war that it is. We ought to nationally read the names of the dead and plan monuments, as we do for fallen soldiers; we should graphically describe, and publish, the full extent of what it means to fight, and lose, to this disease. "It's time to make people scared and uncomfortable," Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal wrote in the Times on Monday. "It's time for some sharp, focused terrifying realism."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Until then, the pandemic — the real pandemic, that is, the ugly suffering and Instagram-unworthy costs of our leaders' negligence — remains invisible. Daily life may be unrecognizable from 10 months ago; we wear masks in stores, have kids learning on laptops at home, we pass more and more empty storefronts on Main Street. But particularly for people who've been diligent about following the rules since the start, there's little to even mark the change in routine from the better days of the late spring, to the dark, passing moments of our current second wave. As a whole, as a nation, we haven't yet been shocked into the panic and revulsion we all need.

Instead, we carry our experiences personally and privately: a run that takes us past the temporary tents of a triage hospital; a food bank line in our neighborhood that we hadn't noticed before; a shift picked up to cover a colleague whose grandpa has died. It's not that the COVID-19 crisis doesn't have a face, after all: it has millions. But each remains impassive behind the obscurity of a mask and the moment, grieving and worrying and living or dying in his or her own internal war — every one worth a thousand words.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.