The pandemic made me a better teacher

What I learned from teaching over Zoom

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I don't want to overstate this.

It's not as if I was an Attila the Hun-like teacher before COVID-19 and teaching on Zoom. But it is undeniable — I'm a better professor today than I was a year ago.

Why? Because a year of isolation has made all of us much more aware of the burdens we carry, and of the psychic toll that young people, in particular, are under. It has made me much more appreciative not just of the challenges they face, but also of the silent grace with which they bear them. It has made me marvel at their good cheer, made me notice their laughter and their lovely fragility, even more.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In turn, it has made me a kinder and more generous teacher of creative writing. For years, I was a stickler for deadlines. After all, the two careers I've had — as a journalist and a novelist — have both taught me the importance of turning in work on time. You owe it to your classmates, I used to chide my students, to turn in your stories when they are due.

But my students can no longer socialize in a carefree way with their friends. Some of them fail to recognize each other at the store because they are masked and they've only ever met on Zoom. It has been a long, cold, lonely winter in Cleveland, so walks and outdoor activities have not been possible. Many of them are back to living with their families and some are helping take care of ailing parents. Those happy, untroubled college days, when they should feel the pulsating throb of their youth, have been snatched away from them. The future seems even more tenuous than it already did. This past year has turned them into the loss generation.

I used to be a stickler for deadlines because I thought it was my job to prepare them for "the real world," a world filled with demanding bosses and competitive coworkers.

But now we find "the real world" itself is an illusion, brought to a standstill by an invisible virus. The old rules have been thrown out as we scramble to learn how to communicate remotely, how to improvise and juggle the responsibilities of home and work.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

As a professor of creative writing, I spent years agonizing over what I was evaluating. Should it be the final product, which was often a measure of their natural talent? Or the effort they made to improve their writing, the distance between the first draft and the final? Or some combination of both? I spent countless hours worrying over whether a portfolio deserved an A or a B, mouse hovering over the button to lock in a final grade.

This year, I'm tipping the scales towards kindness. Towards accommodation. A student requests an extra day or two to post a story because they are overwhelmed with their other classes? Sure, no sweat. We will manage. We will improvise. We will get through this together. And their gratitude for these small dispensations is something to behold. Kindness, it turns out, is a better motivator than strictness.

Last Monday was a chilly but beautiful day here. The kind of day where, in the past, half the students would've been clamoring for me to hold class outdoors, while the other half protested that it was too cold. Just the thought of this familiar tussle produced in me a deep, sweet wistfulness, the kind of nostalgia I'd tried to suppress as we'd all soldiered on this past year.

So I began class by acknowledging that feeling. I recalled the dark granite steps of the fountain outside the building where we would've sat bundled up against the cold. And the shift in energy, even on Zoom, was palpable. They all smiled that soft, wistful, knowing smile, as if they'd been thinking the same thing. As if they'd also been remembering the same bygone world.

When it came time to workshop student stories, the author of the story we were critiquing wrote in chat that although he looked calm, his legs were shaking with fear. Immediately, his classmates became solicitous of him. There was a flurry of chat messages, empathizing with him. Everyone's critiques became more self-aware and deliberate.

We wound down class with a discussion of Ken Liu's Paper Menagerie. It's the story of a Chinese-American boy who is ashamed of his immigrant mother. It is only into adulthood, long after her death, that he hears her full story and recognizes what he has lost.

None of the students in my class on that day were immigrants. But many, I'm sure, have had difficult relationships with their parents. The story affected them deeply. Some started crying during the discussion. One young woman said the story made her wonder how she would take care of her parents in the future, how she would show them her love. I told her that if she was asking herself these questions, she was in a good place. That she would know the answers when the time came.

Several students kept wiping away their tears but one student cried openly throughout the entire discussion. This is the same student who, the previous week, had been so moved by the closing paragraph of another story, by the correct inclusion and placement of a single word — "named" — that she had had a similar reaction. On that day, I'd stopped the discussion to commend her on her emotional response, because at its best, isn't that exactly what literature is supposed to do? To move us, to humanize us, to make us feel the tug of our shared humanity? To dazzle us with language, that simple arrangement of words strung together, until they transcend into something ineffable, like music, something that pierces the human heart.

And so, I let her cry. Her tears were a tribute, not just to Liu's story, but to the power of literature in general. I checked in with her immediately after class ended to make sure nothing else was amiss and she assured me that things were fine. She's simply a sensitive, careful reader who thankfully has not built up the crust of guardedness that age confers on so many of us, who knows that public tears are often a public service, because it allows others to be vulnerable.

As for me, I'm going to give my students every benefit of the doubt this semester and hopefully, through the rest of my teaching career. I'm going to work on being a softer, more open-hearted teacher and not worry about this diminishing my authority in the classroom. I'm no longer satisfied with teaching the craft of writing or even the art of writing. Rather, I want to demonstrate how literature works in the real world, how it humanizes, how it performs essential work not just in the individual human heart but in a society that is hollowing out for lack of empathy. If my students can be brought to tears by the story of one immigrant family because they can immediately see their own family dynamics in this story, then there is hope for democracy, for our torn-apart country.

Performance reviews, deadlines, accountability — all these things matter in the real world. But what also matters is human kindness and compassion. The world will teach them the former soon enough. But I want to send my students out into that world armed with the latter attributes. This is what I can teach them. This is what this year of living quietly has taught me.

Thrity Umrigar is the bestselling author of eight novels, including The Space Between Us and Everybody’s Son. Her latest picture book, Sugar in Milk, is a recounting of an ancient legend about immigration and the importance of kindness. She lives in Cleveland, Ohio.

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

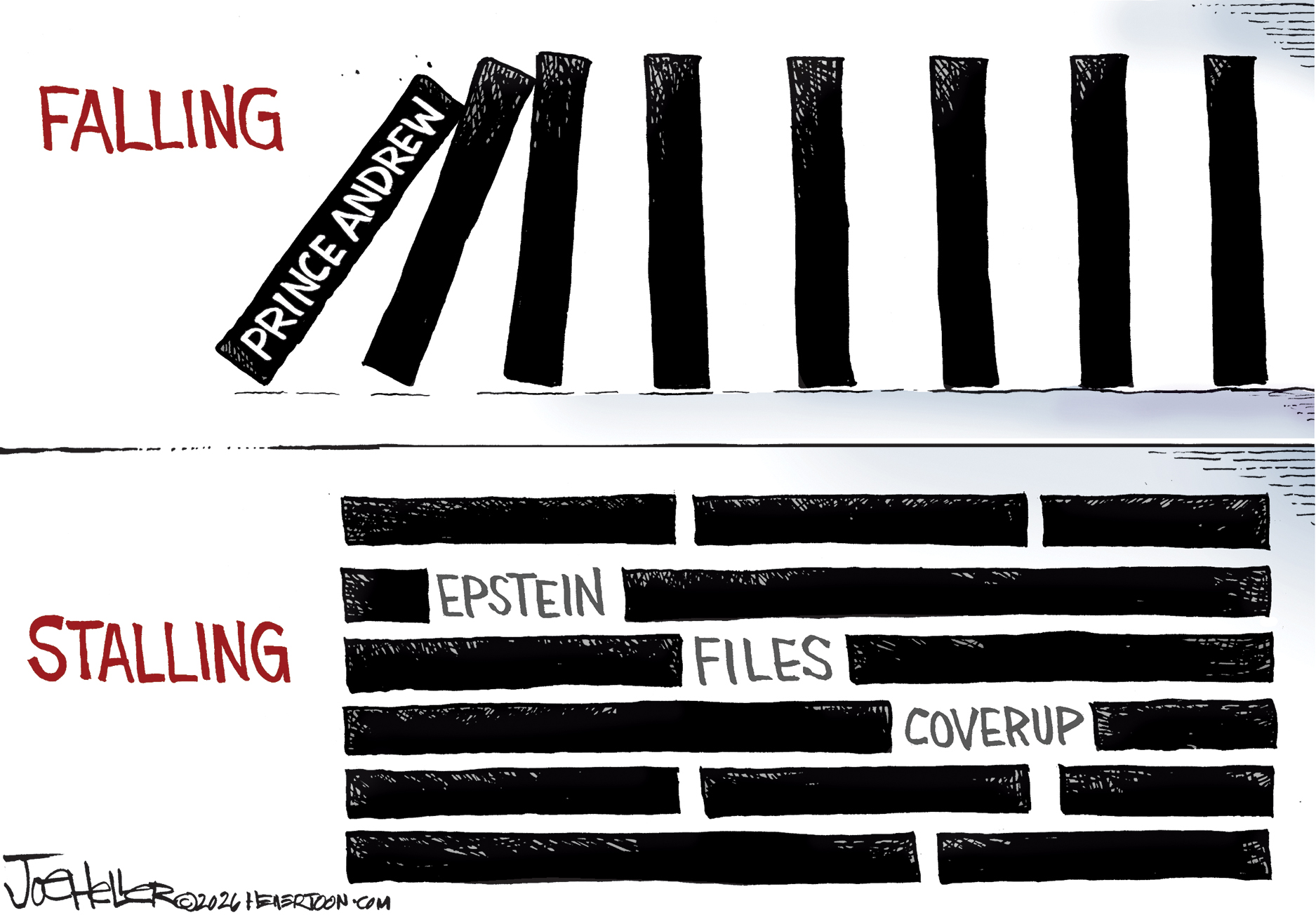

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more