The deadly heat wave frying India and Pakistan

India is enduring its hottest spring in at least 122 years

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

India and Pakistan have, for weeks now, been gripped by a record-breaking heat wave that has already killed dozens. Here's everything you need to know:

How hot is it in India and Pakistan?

Since the extreme heat began roughly two months ago, India has experienced "its highest March temperatures and third-highest April temperatures in 122 years of records," while Pakistan reported its "hottest April on record," CNBC writes. For example, temperatures in Jacobabad, Pakistan — "already one of the hottest cities in the world," Vox notes — recently reached over 120 degrees Fahrenheit. And in India's New Delhi, temperatures climbed last weekend to a sweltering 116 degrees Fahrenheit. It has been so hot, in fact, that birds are falling from the sky, plagued by heatstroke.

"We are living in hell," Nazeer Ahmed, a Pakistani man, told The Guardian at the start of May.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With any luck, impending monsoons will break the spell … but there is, of course, no way of controlling the timing of that relief. "If the monsoon is delayed or doesn't come or arrives in June, then this period could be even longer," Vimal Mishra, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, told The Washington Post.

To make matters worse, Pakistan is now also dealing with a deadly cholera outbreak linked to contaminated drinking water.

What effect has the heat had?

The unbearable temperatures have upended both life and work in the region.

For one thing, a large portion of the workforce in both India and Pakistan is in agriculture, meaning workers are forced to choose day after day between dangerous weather conditions and their next paycheck. Meanwhile, the crop harvest has taken a toll — in India, for example, "the yield from wheat crops has dropped by up to 50 percent in some of the areas worst hit by the extreme temperatures," The Guardian reports. "This is the first time the weather has wreaked such havoc on our crops in this area," a Pakistani farmer told the publication. "The cultivation has decreased; now very few fruits grow. Farmers have lost billions because of this weather. We are suffering and we can't afford it."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Elsewhere, an increase in demand for electricity and the resulting stress on the power grid has led to hours-long power outages, limiting access to critical cooling mechanisms. And mountain glaciers are melting at a faster-than-normal rate, leading to infrastructure-damaging flash floods in Pakistan, Vox writes.

Are heat waves normal for this time of year?

For this region, yes; temperatures are typically at their highest in May, prior to monsoon season. But 2022's hot spell is unusual considering it's "happening much earlier in the season than normal, before summer weather typically sets in," Vox writes. "[I]t caught people off guard."

"Ordinarily, there is a slow creeping up [of temperatures] into the summers," Suruchi Bhadwal, director for earth science and climate change at Delhi's Energy and Resources Institute, told Vox. "When the temperatures started rising and stayed consistently high, it wasn't predicted." This wave is also spread "out over a much larger area, covering most of the landmass across Pakistan and India instead of concentrating in a few pockets.

That said, even with all its particulars, this "extreme weather event" is really just par for the course these days, David Wallace-Wells writes for The New York Times. "We want to call events like this 'extreme,' but technically we can't, 'because they're not rare anymore,' [climate change lecturer] Friederike Otto told me, from London, just as the heat wave reached its April peak," said Wallace-Wells.

Why is this heat wave so severe?

Climate change is more than likely to blame for the severity of this deadly South Asian wave. A recent analysis from the United Kingdom's Met Office, in fact, found that climate change has made extreme temperatures like those in India and Pakistan 100 times more likely, CNN reports.

"Spells of heat have always been a feature of the region's pre-monsoon climate during April and May," Nikos Christidis, the study's lead researcher, told CNBC. "However, our study shows that climate change is driving the heat intensity of these spells."

If climate change weren't a factor, a crippling heat wave such as the one that previously passed through the region in 2010 would only be expected about once every 312 years, the study concluded. But once global warming and the like come into play, the odds of such extreme temperatures "increase to once in every 3.1 years," CNN writes.

What can be done?

Unsurprisingly, it's a tricky problem to solve. For one thing, survival in South Asia now "depends on artificial cooling," which "demands power" typically provided by fossil fuels, which in turn burn up the planet, Vox notes. "It's a difficult tension to resolve, trying to mitigate an immediate problem at the risk of worsening another one."

But there are options. For one thing, South Asian governments could begin to more seriously address the threat of climate change, something they by and large have yet to do. They might also consider measures like "better urban planning, planting trees, green spaces, improved water infrastructure, pollution controls, and more robust weather forecasting" to help ease the pain of unbearable heat.

But South Asian countries shouldn't carry the burden alone — others can help, too, Vox writes. Considering "the bulk of historical emissions came from wealthier countries like the U.S. and those in Europe," the nations that have had a greater hand in climate change "have an obligation to help those facing the consequences now."

Brigid Kennedy worked at The Week from 2021 to 2023 as a staff writer, junior editor and then story editor, with an interest in U.S. politics, the economy and the music industry.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why Biden is banning Alaska Arctic oil drilling now

Why Biden is banning Alaska Arctic oil drilling nowSpeed Read The Biden administration blocks drilling on pristine federal land in Arctic Alaska

-

The new Cold War in the Arctic, explained

The new Cold War in the Arctic, explainedSpeed Read Climate change creates a new battleground for the U.S., Russia and China

-

Climate anxiety is plaguing the world's youth

Climate anxiety is plaguing the world's youthSpeed Read Young people are worried the world will become "a harder, darker, scarier place"

-

What climate change means for Florida's future

What climate change means for Florida's futureSpeed Read "The tide is coming in"

-

The successes and failures of the COP27 climate summit

The successes and failures of the COP27 climate summitSpeed Read Help for poor countries, but no progress on carbon emissions

-

What happened at COP27?

What happened at COP27?Speed Read Leaders and activists met in Egypt at a precarious time for the planet

-

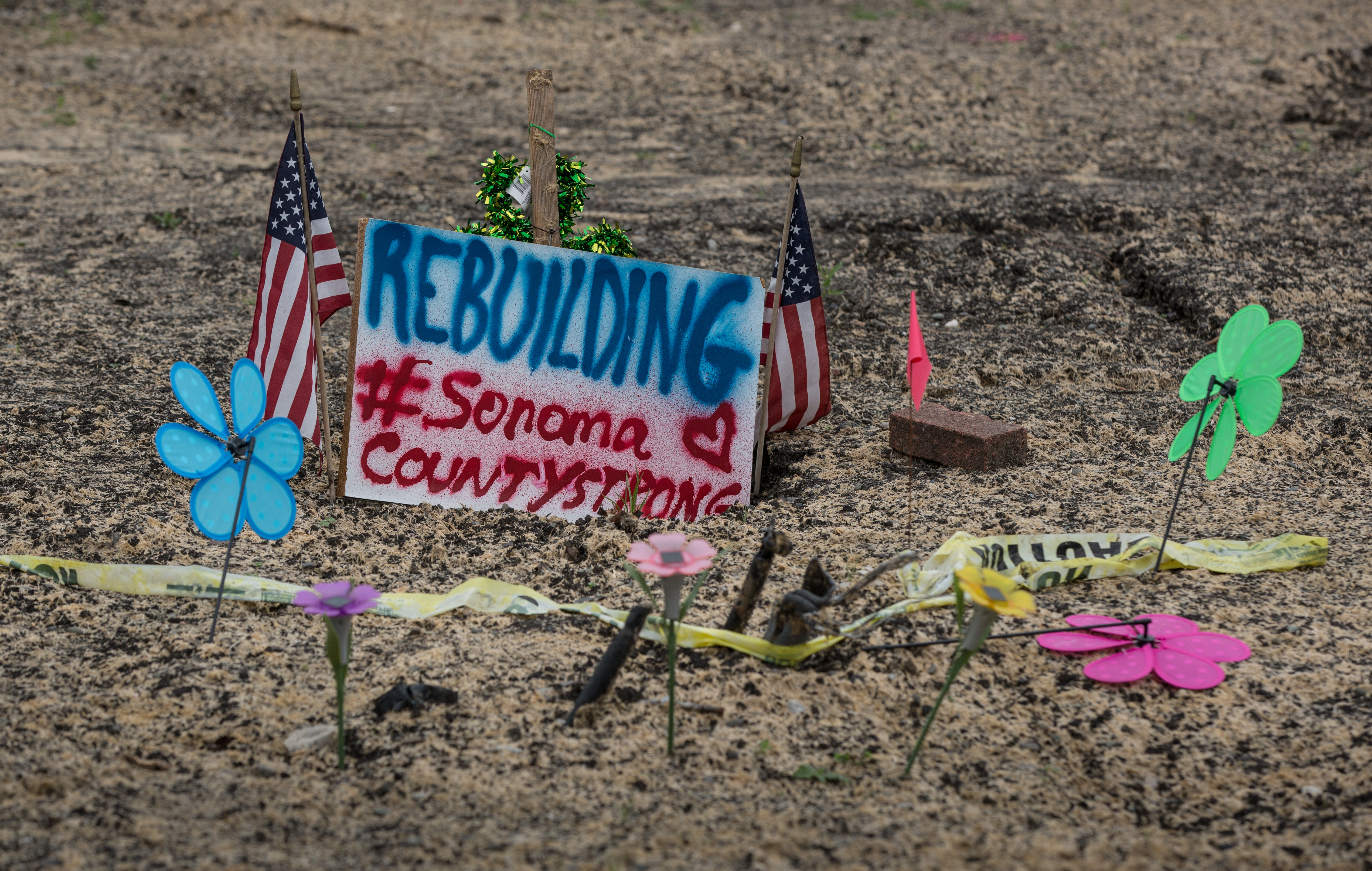

Rebuilding after climate disasters

Rebuilding after climate disastersSpeed Read The instinct to restore homes and businesses in vulnerable areas is being questioned as climate change intensifies

-

The uneven effects of climate change

The uneven effects of climate changeSpeed Read Rapidly-intensifying weather and natural disasters are proving to create lopsided devastation across the globe.