The women of World War I

While most Americans wanted to stay out of World War I, some women were eager for the opportunity to prove themselves

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

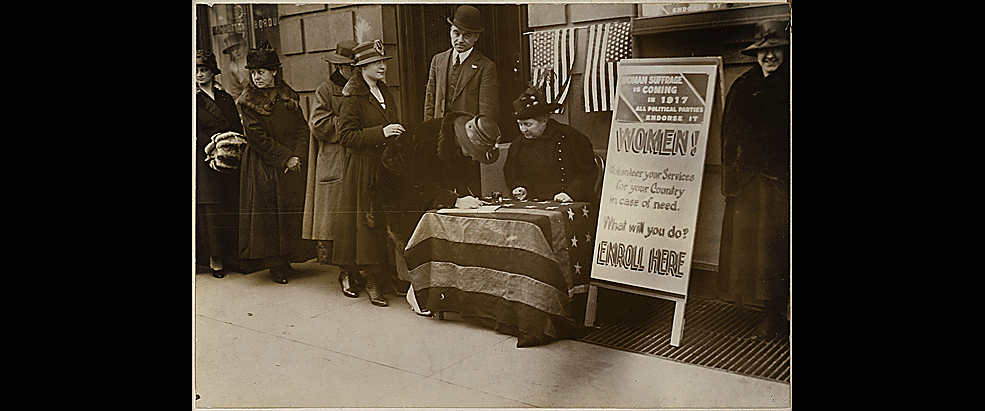

On April 6, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson broke his pledge of neutrality, and America reluctantly entered World War I. While the vast majority of Americans may have preferred the Wilson's original isolationist stance, some women felt differently. For them, the war was an opportunity to prove themselves and participate as citizens.

By the early 1900s, married women were still largely relegated to the home. What money they made was through piecemeal work — stitching, shoe repair, cooking, childcare — done from within their confines.

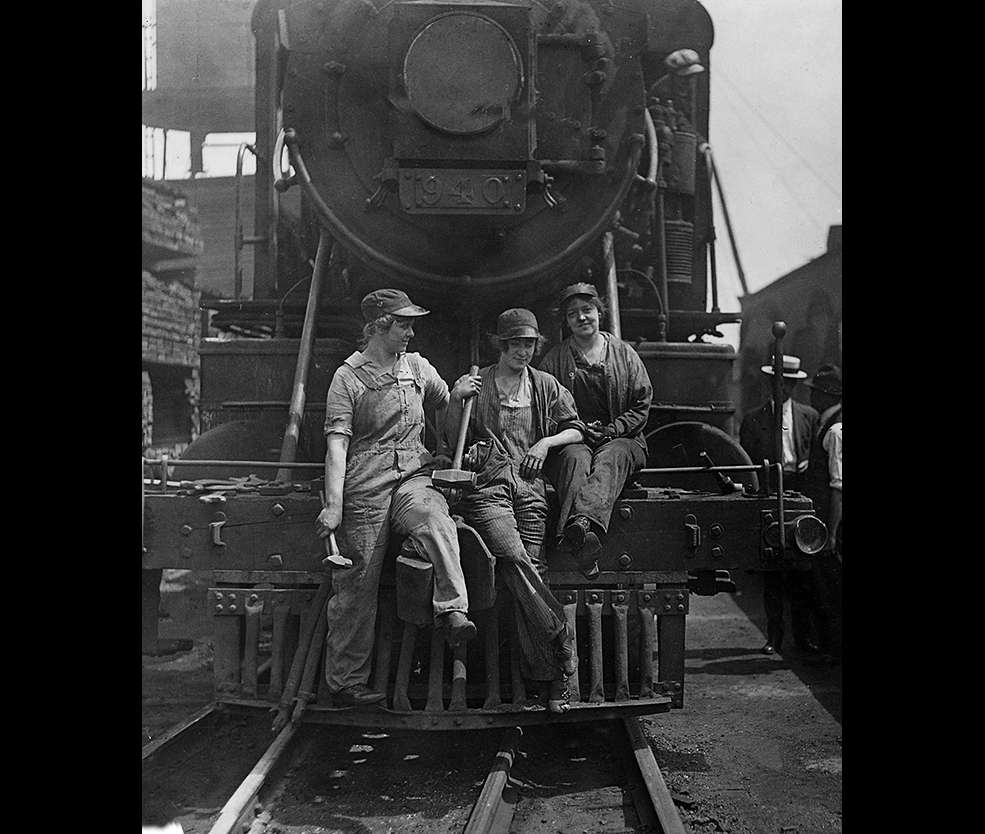

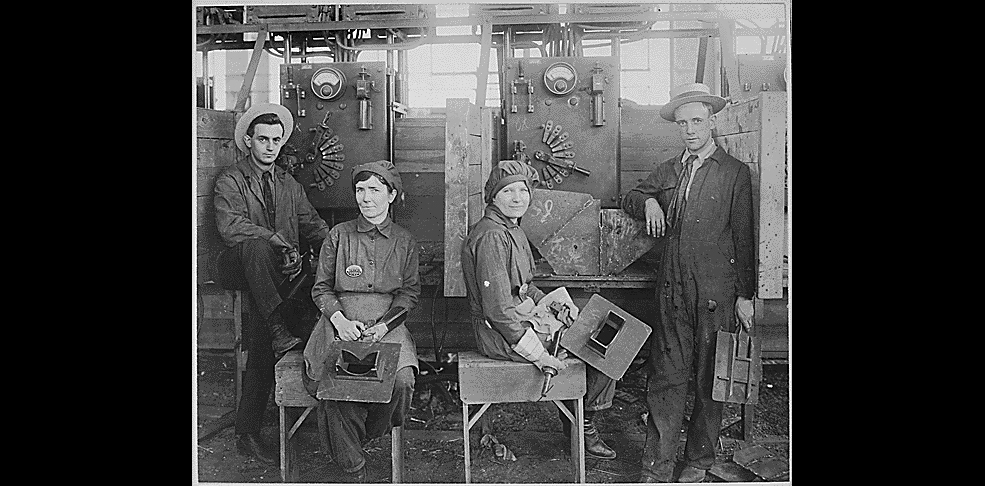

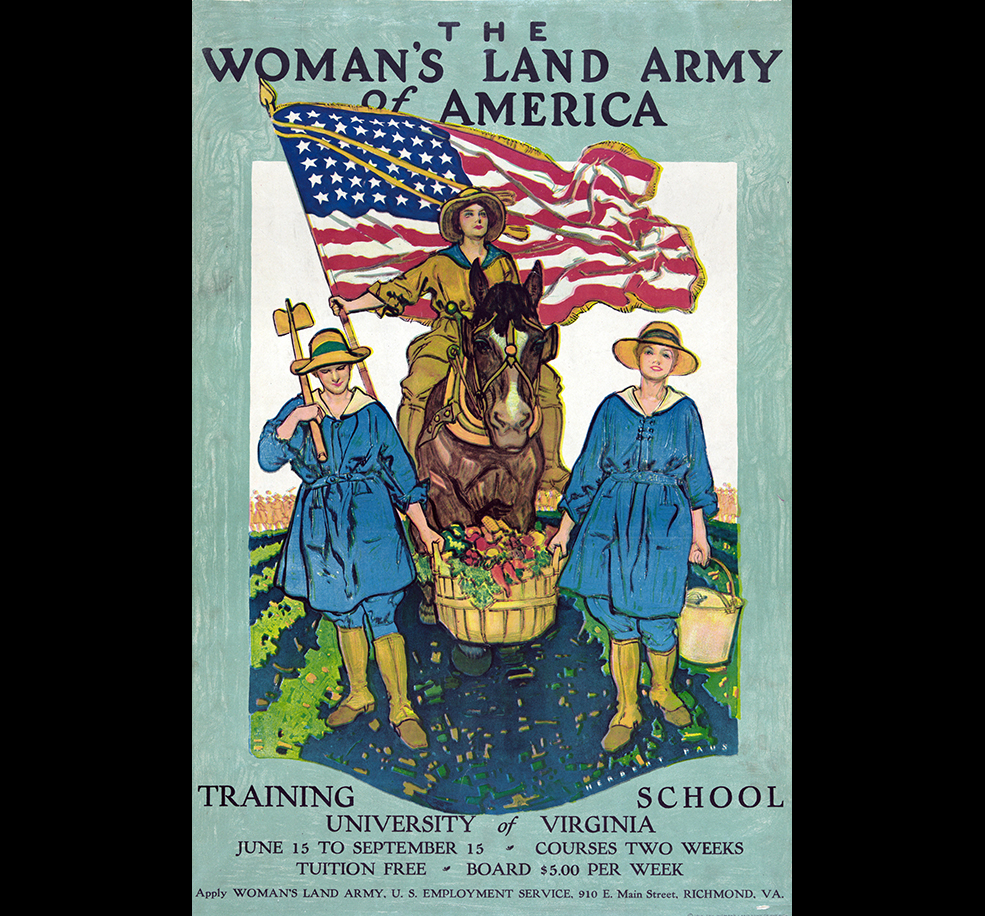

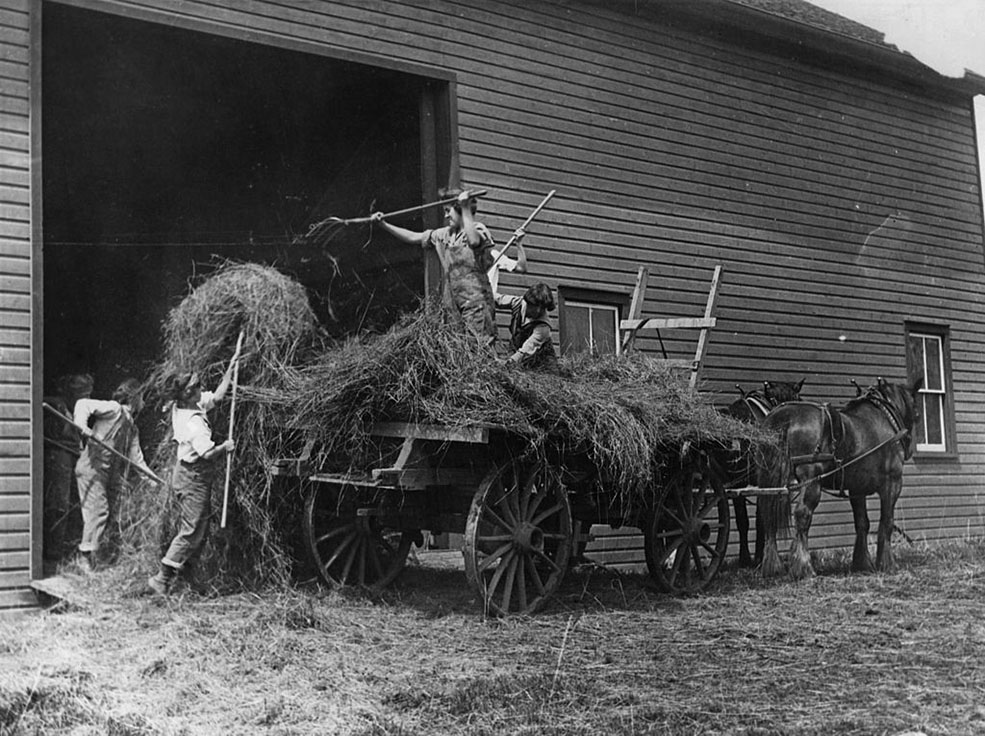

While single women had begun to join the workforce by the outbreak of the war, their industrial contributions, too, were limited to "women's work": textiles, domestic services, and clerical tasks. But the war changed that. As millions of men were called to arms, women, no matter their status, filed out of their homes and into the male-dominated fields of industry, agriculture, and even the military.

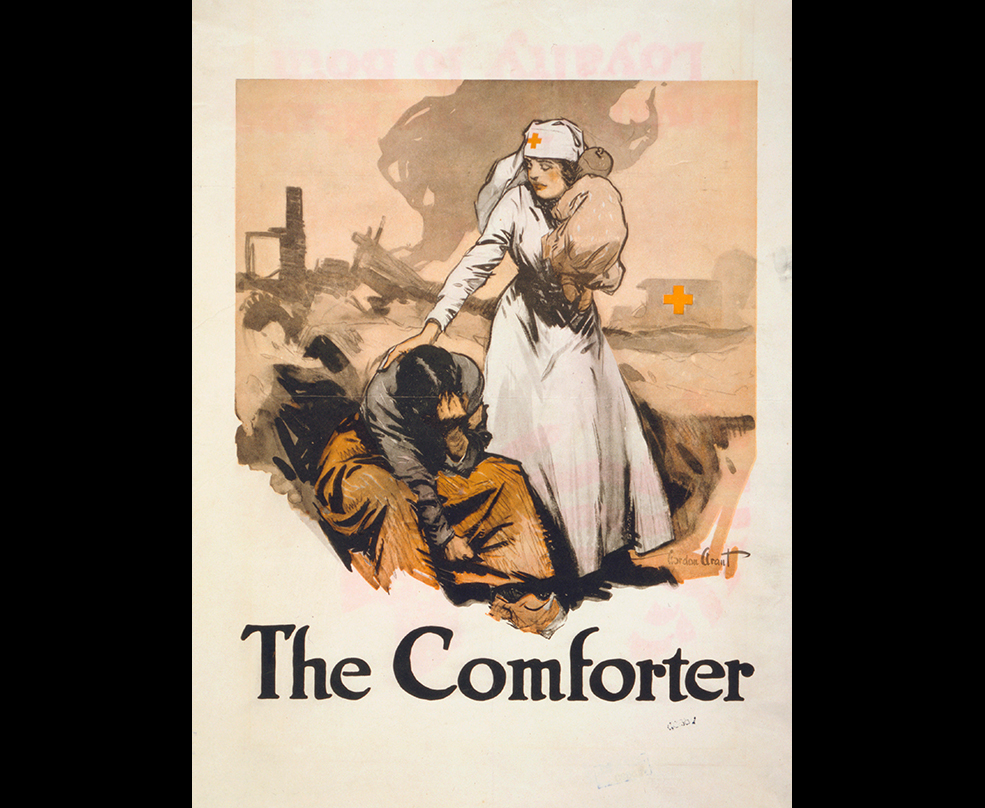

Women were playing a vital role not just in the war, but also in the country's economy. They worked in factories, making ammunition and building weapons, airplanes, cars, and ships. They joined the American Red Cross and civilian volunteer organizations, like the National League of Women's Services, which provided stateside military services from transportation to aid.

They did manual labor, worked on farms, served in local government, and joined police forces whose ranks were depleted. Upper-class women, too, joined the effort raising awareness and funds, sending care packages, or leading conservation efforts among American households.

And, for the first time, women were allowed to join the military. The Army and Navy had such severe clerical shortages that the Navy approved the enlistment of women. By the end of America's first month at war, 600 female Yeomen (petty officers) were on duty, doing office work and serving as translators, recruiting agents, ship camouflage designers, and fingerprint experts, among other things. By the end of the war in 1918, more than 11,000 women had joined the Navy's ranks.

Women weren't just working on the home front, either. Some 25,000 women would travel to Europe, and serve as journalists, telephone operators, drivers, aid workers, and nurses. Some traveled with the Red Cross, while others joined overseas service units created by the General Federation of Women's Clubs to assist soldiers. But many others traveled on an entrepreneurial basis, helping wherever and however they could, even long before the U.S. joined the war.

And their efforts did not go unnoticed. In September 1918, still a few months shy of the war's end, President Wilson, who had previously been indifferent to the suffrage movement, implored a joint session of Congressto guarantee women the right to vote.

"We have made partners of the women in this war. Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil, and not to a partnership of privilege and right? This war could not have been fought ... if it had not been for the services of the women, services rendered in every sphere, not merely in the fields of effort in which we have been accustomed to see them work, but wherever men have worked and upon the very skirts and edges of battle itself." [President Wilson]

The 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote was approved on June 4, 1919.

At the end of the war, as a battle-crippled society tried to return to "normal," many women were forced back into their pre-war gender roles. But the American women's war efforts and the passing of the 19th Amendment paved the way for future generations to carry the fight for equal rights in the century to follow.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Lauren Hansen produces The Week’s podcasts and videos and edits the photo blog, Captured. She also manages the production of the magazine's iPad app. A graduate of Kenyon College and Northwestern University, she previously worked at the BBC and Frontline. She knows a thing or two about pretty pictures and cute puppies, both of which she tweets about @mylaurenhansen.