The chillingly plausible authoritarianism of 'Prophet Song'

This Booker Prize winner shows how democracy can crumble from within

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

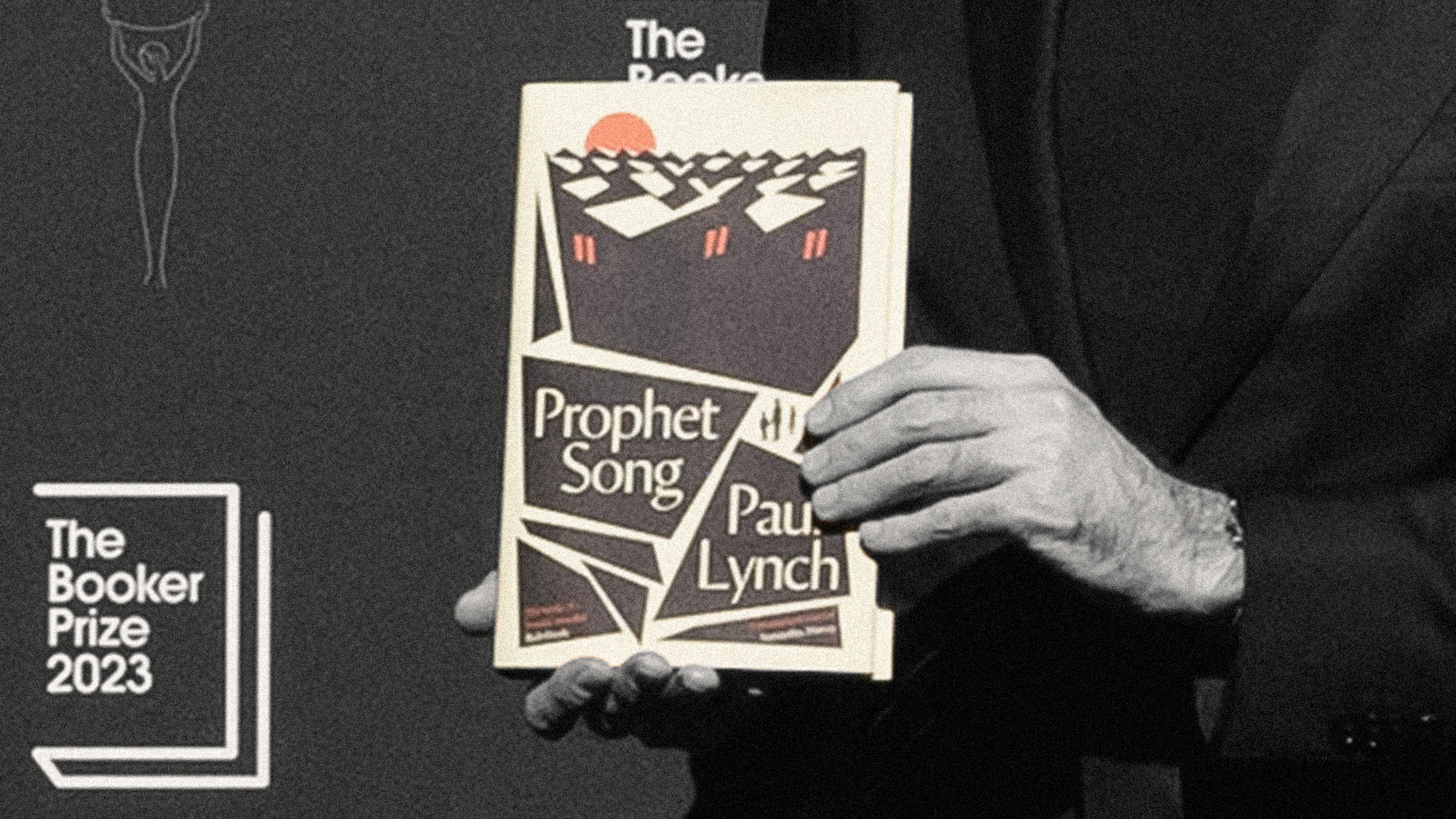

It turns out that the scariest book of 2023 wasn't a horror novel at all, but Irish novelist Paul Lynch's Booker Prize-winning "Prophet Song." Set in an unnamed Irish city (with named landmarks pointing to Dublin) in an alternate version of the present, "Prophet Song" begins with a late-night knock on the door at Eilish and Larry Stack's family home. Larry is out working late — a higher-up in the teachers' union, he is plotting protests against the newly elected (also unnamed) Party and its various assaults on civil rights and human dignity. The visitor turns out to be a young detective in the new Garda National Services Bureau (GNSB), a kind of Irish Stasi or KGB tasked with cracking down on dissenters and troublemakers in the new order.

"It's probably nothing," Larry says nonchalantly when he gets home later and hears about the interrogators. Like so many characters in the novel, he cannot believe that such horrors are on his doorstep. But before long, Larry is disappeared without explanation by the GNSB, plunging Eilish into a waking nightmare of caring for their four children, ranging in age from a baby to a pair of angsty high schoolers, as society disintegrates around them. It begins with street violence and mass arrests, then escalates into full-blown civil war.

A template for America

The structure of "Prophet Song" resembles, more than anything else, the grim 1983 nuclear war drama "Testament," a film about a California woman whose husband never returns from San Francisco the day of a surprise nuclear attack, and who must then navigate her family through unimaginably grim new realities. In both stories, the aperture is narrow, as we see nearly everything through the eyes of the matriarch. There are no cutaways to generals launching counter-strikes or presidents on TV addressing the nation. And while it is set in Ireland, "Prophet Song" is the most realistic look yet at how a new American civil war might unfold — fascists are elected and immediately set about chipping away at the constitutional order bit by bit, so that many people hardly even notice what has been lost until it is too late.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In the popular imagination, an American civil war would be a red versus blue affair, with secessions triggering a confrontation between states. You'd be on one side or the other. But Lynch's look at one family's worsening ordeal shows how it would actually be: neighbor versus neighbor, towns and cities divided against themselves, rebel armies creating no man's lands on intra-city bridges, children's hospitals targeted in aerial bombings. When Lynch's Irish citizens turn against one another, they do so with a savage ferocity. And it is easy to imagine this happening in the United States after an authoritarian takeover, given how Republicans and Democrats are not separated into neat geographic enclaves.

Time to leave

In addition to her children, all of whom are losing it in one way or another, Eilish is also tasked with caring for her elderly father Simon, who is sliding almost imperceptibly into senility. At one point, Eilish's sister Áine pleads with her to flee to Canada, where she lives, and delivers the novel's most unforgettable line. "History," Áine says, "is a silent record of people who did not know when to leave."

Eilish, though, will not abandon Simon or Larry and refuses her sister's entreaties to escape. In the interim, Eilish is purged from her research firm, watches her adolescent son Bailey descend into madness and tries desperately to prevent her oldest son Mark from being drawn directly into the maelstrom. As in "Testament," not everyone in this little family makes it, and the ending is somewhat ambiguous, which may not satisfy some readers. But its depiction of wealthy Europeans experiencing the depths of human depravity, violence and complicity first-hand is chillingly plausible. As a way of considering how despots could stage a takeover of the United States and then use brute force to consolidate their new tyranny, "Prophet Song" is as illuminating and haunting as any real-life history of descent into authoritarianism.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

The year’s ‘it’ vegetable is a versatile, economical wonder

The year’s ‘it’ vegetable is a versatile, economical wonderthe week recommends How to think about thinking about cabbage

-

The biggest box office flops of the 21st century

The biggest box office flops of the 21st centuryin depth Unnecessary remakes and turgid, expensive CGI-fests highlight this list of these most notorious box-office losers

-

Mail incoming: 9 well-made products to jazz up your letters and cards

Mail incoming: 9 well-made products to jazz up your letters and cardsThe Week Recommends Get the write stuff

-

The 8 best superhero movies of all time

The 8 best superhero movies of all timethe week recommends A genre that now dominates studio filmmaking once struggled to get anyone to take it seriously

-

Book reviews: ‘Hated by All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling of the Conservative Mind’ and ‘Football’

Book reviews: ‘Hated by All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling of the Conservative Mind’ and ‘Football’Feature A right-wing pundit’s transformations and a closer look at one of America’s favorite sports

-

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’

One great cookbook: Joshua McFadden’s ‘Six Seasons of Pasta’the week recommends The pasta you know and love. But ever so much better.