3 ways social media pulls us into dumb and dangerous debates

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

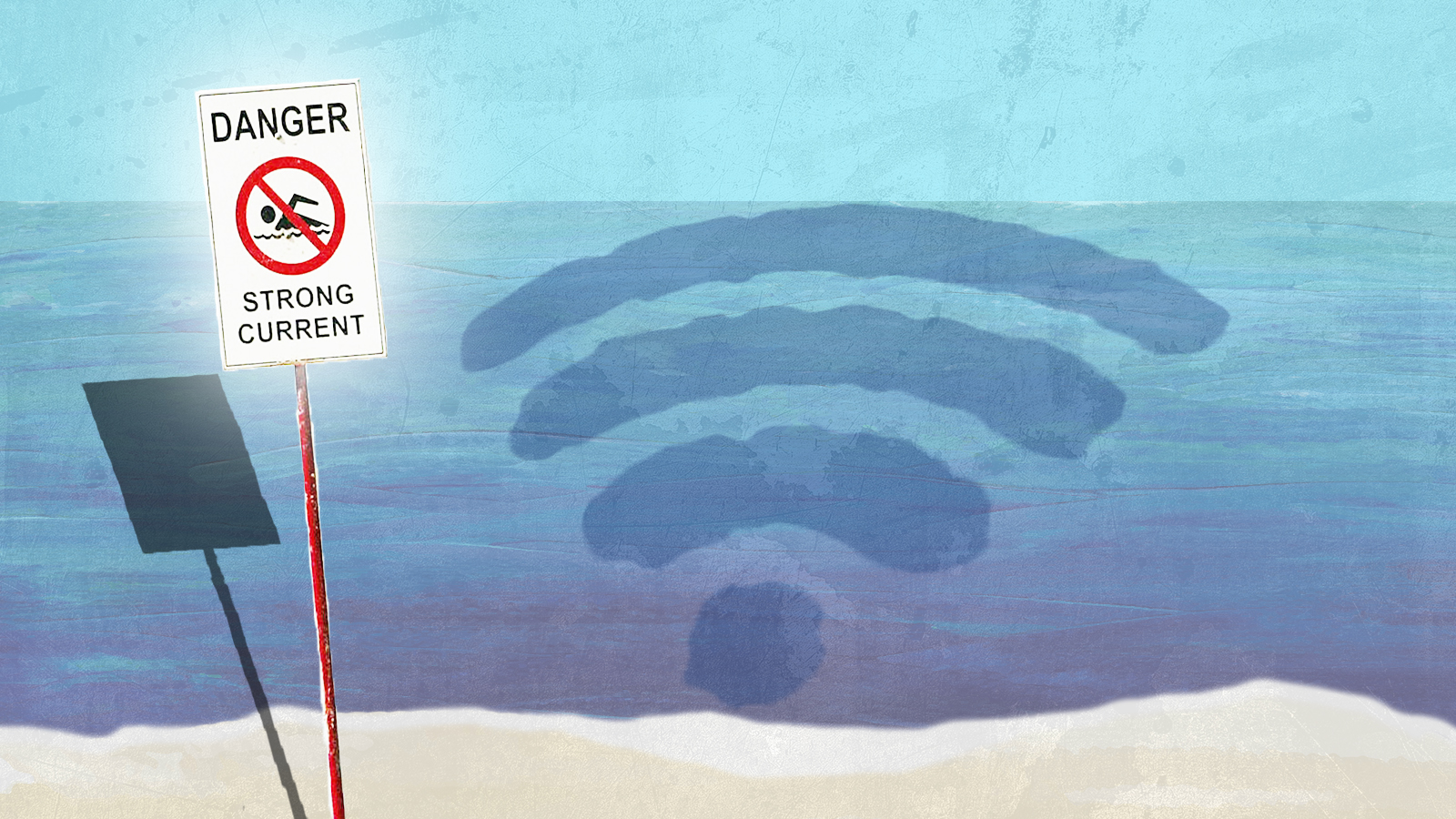

Social media plants and elicits opinions in us like a rip current, those dangerous flows of ocean water that can rapidly pull a swimmer out past the breakers, well beyond their depth.

The way to escape a rip current, as children learn at the beach, is to disengage from it by swimming sideways, parallel to the shore. This sounds very simple and often can be easily accomplished, even by weak swimmers, because these powerful currents are frequently only a few feet wide. But in the adrenaline-hazed moment, swimming sideways doesn't make much sense. You don't want to go sideways. You want to get back to the beach. Surely you should attack the problem head on. Surely you should swim directly against the current. Yet if you do, you'll exhaust yourself and be swept farther out instead.

What I want to share here are three ideas that can help us escape such dangerous currents of online public discourse — concepts which, if we can keep them in mind and scrutinize our own behavior and thinking accordingly, can help us swim sideways. None are original to me, but I believe the connection is, and that knowing each helps us understand the workings of the others.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

1. The scissor: This term first appeared in a short story by Scott Alexander, the psychologist behind the popular blog, Slate Star Codex, and later picked up by The New York Times' Ross Douthat. In Douthat's summary, a scissor is "a statement, an idea, or a scenario that's somehow perfectly calibrated to tear people apart — not just by generating disagreement, but by generating total incredulity that somebody could possibly disagree with your interpretation of the controversy, followed by escalating fury and paranoia and polarization, until the debate seems like a completely existential, win-or-perish fight."

A scissor works by suspending our theory of mind, which means making it impossible to understand how other people come to different conclusions and decisions because they have different experiences, wants, and principles. That's why a scissor requires conversation to start cutting, as Alexander's narrator says. If you read it in isolation, it "just seems like a trivially true or trivially false thing" — but if you encounter someone disagreeing (and on social media, you will), the current begins to pull. (The example that occasioned Douthat's column was the Covington Catholic controversy of 2019.)

My only critique of the scissor idea is I think it may set too high a bar. Maybe we need a term for similar but slightly less intense controversies. Take "Imagine thinking ... ," a popular and very scissor-y turn of phrase, and one employed about all sorts of issues that theoretically shouldn't rise to scissor level. Despite what its form suggests, "Imagine thinking ... " is not an invitation to imagination. It's precisely the opposite, as historian Paul Matzko has observed. It's a declaration "that the object of derision is so outlandish that [the speaker] can't imagine it being correct." That's Douthat's "total incredulity," but in my (limited) observation, "Imagine thinking ... " is deployed in political debates where reasonable people ought to be able to see how other reasonable people can disagree, like whether to expand the welfare state.

2. Take trap. As defined by its coiner, writer and editor Samuel D. James, a take trap is "a situation in which the perceived benefits of forming an opinion on something quickly and sharing that opinion outweigh both the learnedness of the opinion and even the heartfelt sense of the opinion's importance. In other words, a take trap is when you absolutely, positively need to post what you think about issue X, even if what you think was mostly put there by accident."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

James sketches a brief scenario to show how a take trap springs. An ordinary social media user, dubbed Steve, sees lots of his friends and favorite influencers talking about some issue online. He reads a little, "but most of the articles are paywalled, and he doesn't really have time or interest to dive further." As the discussion continues, however, and people Steve both likes and loathes begin to comment, Steve starts to feel compelled to do the same, though he's barely better informed than he was when the matter came to his attention. He "doesn't want to be the kind of person who doesn't say anything about important stuff," so he posts something, "using a makeshift combination of his major political or religious views to say something general about the headlines he's been seeing."

If a scissor or near-scissor topic is what gets the rip current going, the take trap pulls the swimmer in. That can happen whether the swimmer is sucked into the current or deliberately dives in, trying to swim against it, perhaps altruistically, for the sake of others already being carried along. You can be take-trapped when you're going with the dominant flow of opinion in a controversy — but you can be equally take-trapped when you try to speak up to save the wrongheaded mob from their own delusions.

3. Epistemic secession. This is what can happen when you've been carried out to sea. Epistemic secession is a step beyond losing your capacity to understand why others reach different conclusions and decisions. It's rejecting the informational basis for those decisions altogether.

As explained by its originator, Jonathan Rauch, in his new book, The Constitution of Knowledge, epistemic secession is "not just confusion and disorientation but a cultic alternative reality. ... Inside the cultic bubble, every question has an answer, every implausibility an explanation, even if the answer is a change of subject or the explanation is that you cannot believe your own eyes and ears."

Rip currents don't go forever. Past the breakers, they dissipate. Currents of online discourse do, too, but they don't restore you to where you were before you were pulled in. And if you're pulled in again and again, you begin to tire. It becomes easier to be caught up once more. It becomes more difficult to remember to swim sideways, or to swim back toward safety after the dissipation. Epistemic secession might start to appeal, I suspect, amid such an exhausting cycle. It's wrong, but it's restful. You don't have to swim so hard anymore.

The internet is, in the words of comedian Bo Burnham, "a little bit of everything, all of the time." Its ethos insists "apathy's a tragedy, and boredom is a crime." It won't stop making currents, but we don't have to drown.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?

Media: Why did Bezos gut ‘The Washington Post’?Feature Possibilities include to curry favor with Trump or to try to end financial losses