Does anyone actually know what's good anymore?

From movies to restaurants, the problem of rating inflation has ruined reviews

When Eater announced this week that it is getting rid of its starred restaurant reviews, I admit my first reaction was disappointment. Though I'm a professional critic who should really know better, I'm as guilty as anyone of having opened a review only for my eyes to make a beeline down the page to check its rating first.

Eater's move to kill its star system, though, reflects a growing trend in food criticism, following decisions at the San Francisco Chronicle, the Los Angeles Times, and The Infatuation. Unfortunately, that trend hasn't quite reached the worlds of film, TV, book, music, and video game criticism, where scaled ratings are still quite common. The problem is, though, that rampant grade inflation and review aggregators have made it so that anything with a less than perfect score these days qualifies as "bad."

Eater's chief New York City food critic Ryan Sutton touched on this in his argument against scaled rating systems, recounting the time he meant to praise a chef with a two-out-of-four rating for her turkey chili only for it to be received entirely the wrong way. "[T]he larger lesson," he concludes, "is that even when a critic capably wields the primary weapon in their arsenal — words — the starred rating at the end of a review can still cause more confusion and disappointment than clarity." Plus, as Sutton points out, "Two stars for two different restaurants rarely mean the same thing, even when doled out by the same critic."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And for most readers, the nuance between something being rated two stars or three stars isn't even what's important; only that it's not a perfect score. It's difficult to pinpoint when and where the trend in review inflation started, although it's most noticeable now in crowd-sourced business reviews like those on Yelp, Uber, Amazon, or Airbnb. In one study of 1,000 online shops cited by The Wall Street Journal in 2017, for example, 4.3 stars was the "average" internet product rating, not 2.5 stars like you'd maybe expect. "Yelp says 46 percent of the reviews we give local businesses are five stars," the Journal added, noting also that "Uber drivers can get the boot for relatively minor ratings dips … [s]o it feels socially awkward to give less than five stars, even if your driver's car kinda smells." Scaled rating systems have functionally become a way to warn others away from a purchase, rather than to honestly evaluate it.

Art and entertainment criticism has also become a blunt instrument for warning people away from something. Part of that is because even the best-intentioned professional reviewers now have their writing translated through aggregators like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic, which spit out scores to be displayed on rental websites, alongside the runtime and the MPAA rating. Even book reviewers, who historically haven't used star ratings to the same extent as film and TV critics, now get aggregated as "rave," "positive," "mixed," and "pan" on LitHub's Bookmarks website. The result, though, is a haphazard system for gauging whether or not something is worth your time. "I feel like [Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic] have created a sense that there's an answer to whether a movie is good or bad when really that's a very personal question," Vox's Emily VanDerWerff told FiveThirtyEight, adding: "Because it looks like math, we have it in our head that it's somehow objectively true, but in reality, it's all based on subjective experience."

And ratings just keep going up, making them even more unhelpful. Experts are divided about why, although almost certainly advertising is driving part of it: The film industry loves to use those aggregate scores to sell their movies. Reviews on Fandango.com, for example, skewed higher than other aggregates in 2015 "because of the weird way Fandango aggregates its users' reviews," a FiveThirtyEight investigation found, noting that "while other sites that gather user reviews are often tangentially connected to the media industry, Fandango has an immediate interest in your desire to see a movie: The company sells tickets directly to consumers." (Fandango acquired Rotten Tomatoes in 2016, and now includes both scores on its website).

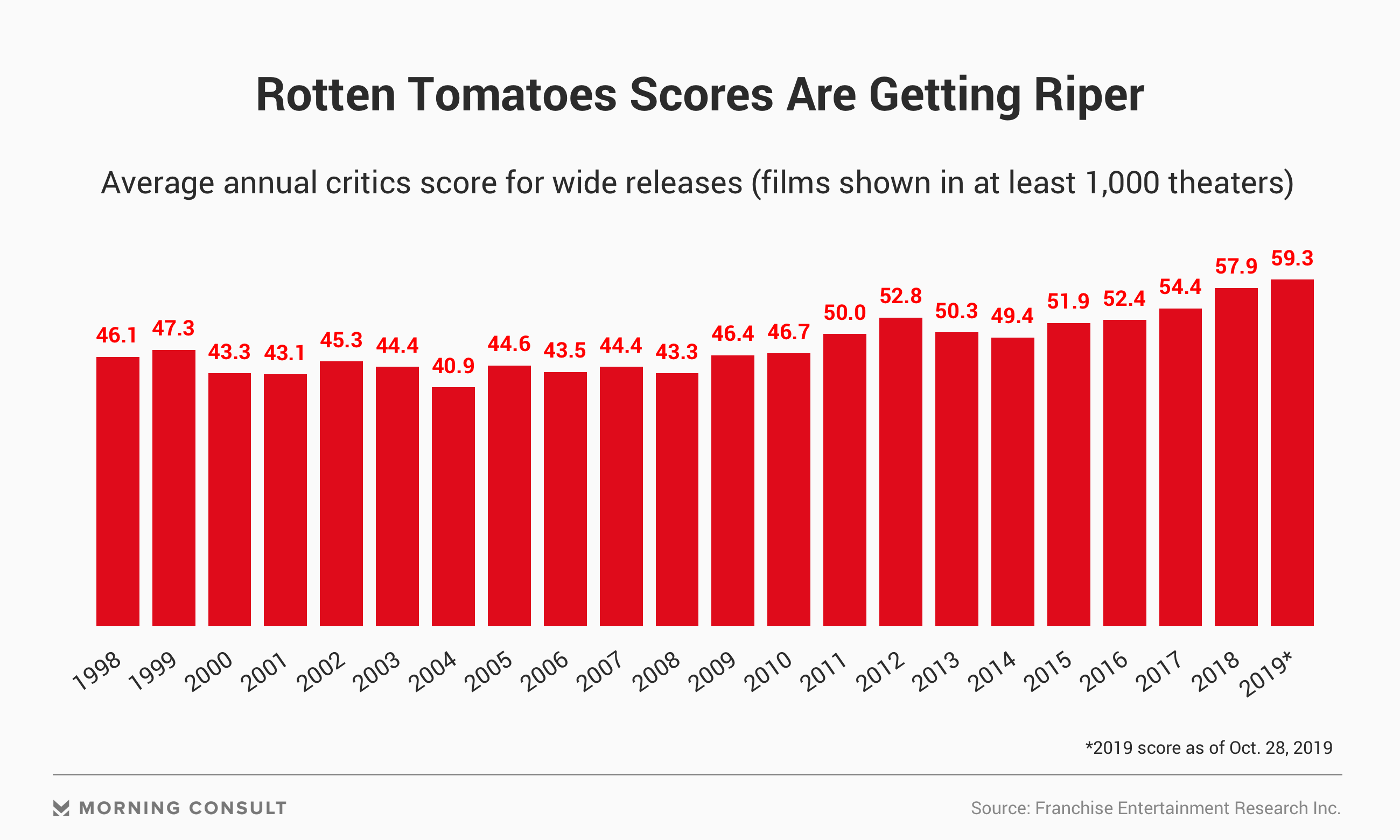

Rotten Tomatoes scores are also rising, with the average now hovering around 60 percent. It doesn't mean movies are getting better — as someone who watches dozens of new movies a year, I can assure you that an average score of 60 is unbelievably high! — but that the rating itself is ballooning. Yet "the value of Rotten Tomatoes is helping you separate great from good from terrible," Allen Adamson, a founder of the brand marketing firm Metaforce, told Morning Consult. "And if everything is good or great, it becomes less valuable."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Indeed, these days you can learn absolutely nothing by looking at the Rotten Tomatoes list of the top TV comedies:

Rating inflation has gotten so ridiculous in video game journalism that Metacritic uses an entirely different scoring system. While a grade of 60 is a favorable green Metascore for movies, a video game on the same website would need to get a 75 or above to likewise be considered a positive review. Adding to the confusion, subjectivity, and meaninglessness of the numbers is Metacritic's mysterious weighting system, which "[assigns] more importance, or weight, to some critics and publications than others, based on their quality and overall stature."

Even if art and entertainment critics want to avoid the rating system on their own websites, like Eater's Sutton, their words still ultimately get processed into something more quantitative by the aggregators. And while I think there are some advantages to rating systems if they were to exist in a vacuum, the truth is that inflation has gotten so bad that audiences automatically interpret anything less than a 90 or above as relatively "meh."

The solution, of course, is easy: Just take the time to read the reviews. But sometimes you really do just want to be told what to see. At the time of writing, this weekend's big box office opening, Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, has a 91 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, though it's ranked only as their 46th best movie of 2021. Metacritic gives it a score of 71. RogerEbert.com has it at three-and-a-half stars, Indiewire a "B," and Vulture, which doesn't use a rating system, called it "half a good movie," which Metacritic quite literally interpreted as a 50.

I don't honestly know what any of this means, except that I personally probably won't be bothered. After all, I've heard this other movie, Summer of Soul, is at 99 percent.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The battle over the Irish language in Northern Ireland

The battle over the Irish language in Northern IrelandUnder the Radar Popularity is soaring across Northern Ireland, but dual-language sign policies agitate division as unionists accuse nationalists of cultural erosion

-

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi Coast

Villa Treville Positano: a glamorous sanctuary on the Amalfi CoastThe Week Recommends Franco Zeffirelli’s former private estate is now one of Italy’s most exclusive hotels

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them